RENAISSANCE MAN

A TRIBUTE TO VIRGIL ABLOH BY JAMES WINES

by James Wines

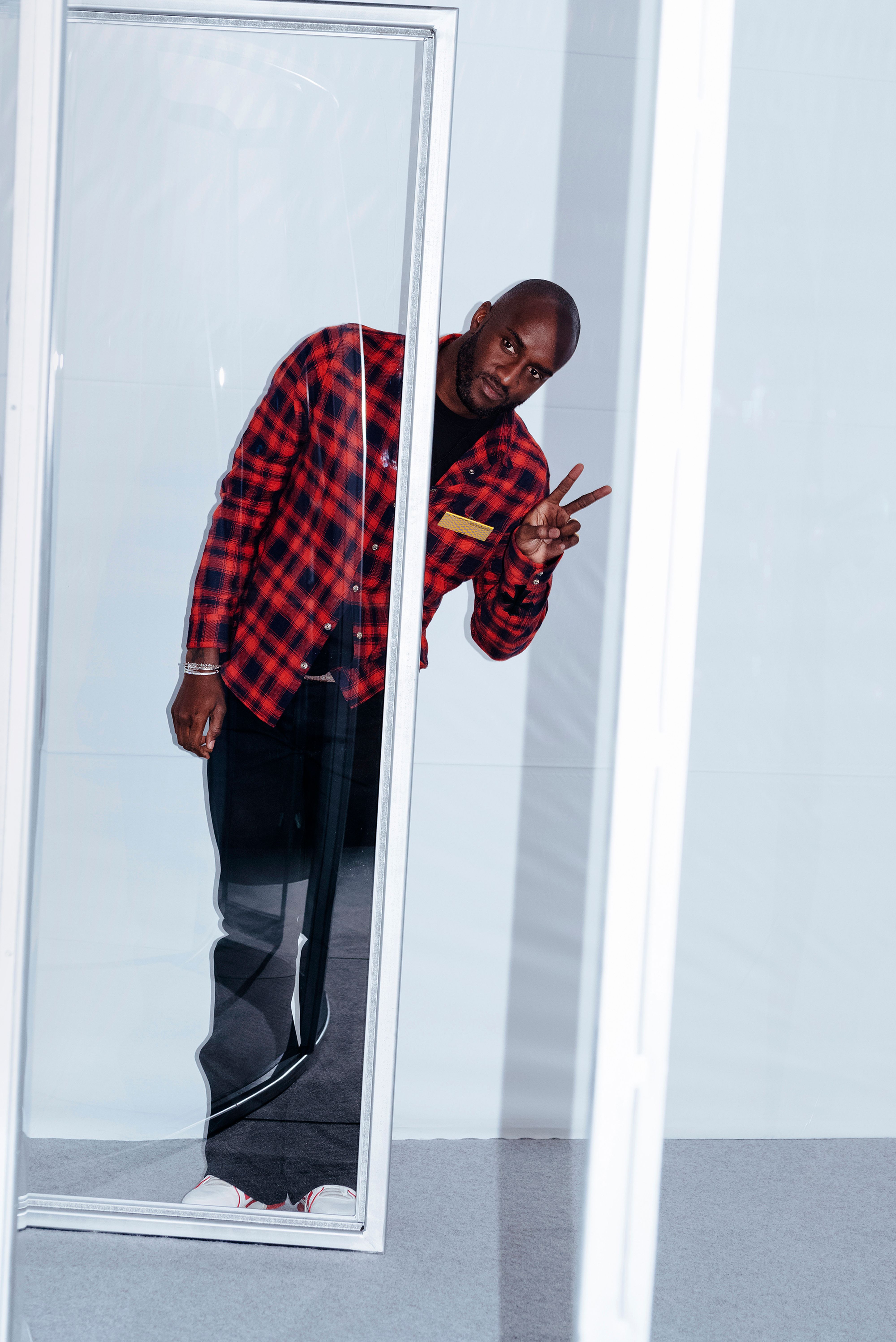

Portrait of Virgil Abloh by Piotr Niepsuj

“Art in its execution and direction is dependent on the time in which it lives, and artists are creatures of their epoch. The highest art will be that which in its conscious content presents the thousand-fold problems of the day.”

— Richard Huelsenbeck, Dada Manifesto

The tragic loss of Virgil Abloh on November 28, 2021, has left a profound void in our cultural world as a whole. This impact continues to expand as a result of his unique contributions to art and design, plus his freedom from convention and predictability. The media has acclaimed Virgil’s influence on fashion, rise in executive power at Louis Vuitton, entrepreneurial success and couture appeal for a younger generation. For me, his supreme achievements have been integrative thinking, community outreach and a new sensibility, based on an aesthetic of rebellion and social equality. Virgil was committed to a ‘between-the-arts’ form of practice, which meant he was always more interested in contextually absorptive ideas than orthodox good design. There was a perverse and liberating quality in his work, which he credited to one of his inspirations: bad design. “Bad design makes you stop and question stuff . . . and sometimes bad design might even be better.”

My environmental arts studio, SITE NY and Suzan Wines’ architectural practice, I-Beam Design, had the pleasure of working with Virgil on two of his fashion showrooms in Korea and Japan during 2020 and 2021. During the process, we became increasingly appreciative of his collaborative spirit and sense of public orientation in both garment design and in the spaces people occupy. We all shared a streetscape connection that allowed our sources of content, choices of materials and delivery of messages to be expressed in a collage-like way, where the fluidity of fabric and rigors of construction seemed part of the same destiny. Virgil’s outreach initiatives reflected every aspect of his mission; “My art practice is the convergence of all creative disciplines into one matter.” As a benefit of his relaxed and inclusive relationship with architecture, interior design, fashion, painting, sculpture, performance and music, there was never a need to justify one’s own territory with defensive rationales. The only objective became the search for a result that ‘worked’ . . . and what worked was a choice of edgy intuition and subliminal consensus among all concerned. Suzan and I always felt that, when fusing our instincts with Virgil’s, the outcome would be a collective art experience and never just another object, place or installation.

For me, the heartbreak of Virgil’s passing has been intensified by the memory of working with Willi Smith — the great 1980s African-American fashion designer — who died at thirty-nine in 1987. Virgil admired Willi’s cross-disciplinary creativity and we had a memorial dialogue, narrated by Oana Stănescu, on September 24, 2020 in association with the Cooper Hewitt Museum’s Willi Smith: Street Couture retrospective, curated by Alexandra Cunningham Cameron. During this Zoom discussion we reminisced about Willi’s commitment to a commonplace public domain and the diversity of people who occupied it. We shared his fascination with random situations, pop culture icons, and his incentive to include the widest possible audience for an art/design experience. As Willi once commented: “I don’t design clothes for the Queen, but for the people who wave at her as she goes by.” In this context, he also collaborated with leading artists of the time — Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Keith Haring, Miralda, Juan Downey, Dan Friedman, Nam June Paik and others — which opened up new thresholds for art and fashion collaboration. Extending these art alliances to the present, Virgil credited his work with Takashi Murakami, Jenny Holzer, the Christos, as well as multiple musicians and designers. In the conclusion to this Cooper Hewitt dialogue, Virgil and I re- confirmed our high regard for Willi’s legacy, how it fueled our own association and (judging from the cultural scene today) what this hybrid assimilation of ideas promises for the future of design innovation.

Although both Willi Smith and Virgil were Black artists, with deep convictions concerning the combative politics of race in America, they never expressed their views with overt negativity — in fact, their presence alone shifted the emphasis to a confirmation of what unique creativity and adaptive social values can accomplish. Their state of positivity was so strong that any respondent had no choice but to feel a sense of exaltation with the aesthetic experience. All of those time-worn and racially charged clichés concerning the obligation of “Black people to set a good example,” as the route to social, personal and professional respect, were transformed into “the example itself as a way of life.” There was no need to backtrack through some condescending analysis of sources and origins, or succumb to protective justifications, because their artistic achievements alone became the embodiment of a supremely optimistic and integrative spirit.

Other sources of inspiration that Virgil and I had in common were reflected in a deep respect for Duchamp, including our interest in both conceptual and environmental art. During our periods of education and early professional development, we tended to view the arts within conventional definitions; but, all of this changed when it became evident that these categorical designations had become oppressively circumscribed, largely maintained for critical sanctions and as impediments to the free-wheeling interpretation of art and design. Like all forms of endorsement to protect exclusivity, these precious “objet d-art” classifications were fair game to be displaced; so, hitting the streets became the essence of liberation. “The generation in New York just before mine was one where the ideology of Pop Art was crashing together with Conceptual Art right at the same time,” Virgil described, “and they were in turn building on the legacy of the previous generation, the legacy of someone like Duchamp. My generation was able to feed off all this, stir the pot and mix in the sociological ramifications of what art is and how it can break the barrier of high culture and relate to real life, regular people.” From my perspective, as an environmental artist and emerging architect in the early 1970s, I described my own direction as; “De-architecture — a way of dissecting, shattering, dissolving, inverting, and transforming certain fixed prejudices concerning the design of buildings, in the interest of discovering revelations among the fragments.”

In concert with our desire to challenge prescriptive constraints in the arts, Virgil, Suzan and I also shared a passion for European art history. In Virgil’s words, studying the Renaissance completely “rewired my brain.” Since this epoch is revered as the universal definition of high art, our commitment to questioning classifications would seem like a contradiction of intent. To the contrary, the Renaissance was a quintessential challenge to Greco-Roman stylistic residuals during the time period, in favor of what became that era’s version of an avant-garde. In fact, this earlier revolution laid the groundwork for all subsequent assimilative thinking. A Renaissance professional, displaying an ‘Art Services’ sign over the door, was obliged to supply full-package proficiency. These responsibilities included whatever the client required — architecture, interior design, fresco painting, theater sets, sculpture, print-making, plus additional skills in structural engineering, orchestrations of pageantry, graphic illustration and even some sonnet writing on the side. The ability to synthesize a graceful merging of the arts was implicit in the delivery of 14th-century creativity . . . and the total opposite of 20th-century modernism’s tendencies toward hermetic specialization. In working with Virgil, Suzan and I were constantly impressed by his wide-ranging grasp of sources from history and the opportunities he offered, especially in mind-expansion and overcoming limitations.

Suzan and I constantly try to imagine what our own lives, plus the arts in their entirety, would be like now if Virgil had not passed away. For us — and the multitudes of people his creativity and personality touched — his presence was a constant daily reassurance that the entire spirit of inclusion was supremely preferential to all the prevailing states of exclusion . . . social distancing, political extremism, territorial isolation, economic disparity, racial injustice and invasive warfare. We miss the frequent interactions with Virgil on art projects; but, on a far more poignant and influential level we see him as still very much among us as the continuing equivalent of a Renaissance artist.

“That’s what fashion, art, architecture — these hallowed layers, the last to conform — need: to just be open-minded”

— Virgil Abloh.

Watch this video of Virgil Abloh in conversation with James Wines on the occasion of the exhibition Willi Smith: Street Couture on view at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum from March 13 2020 through October 24 2021. The talk was moderated by the architect Oana Stănescu and recorded on September 23, 2020.