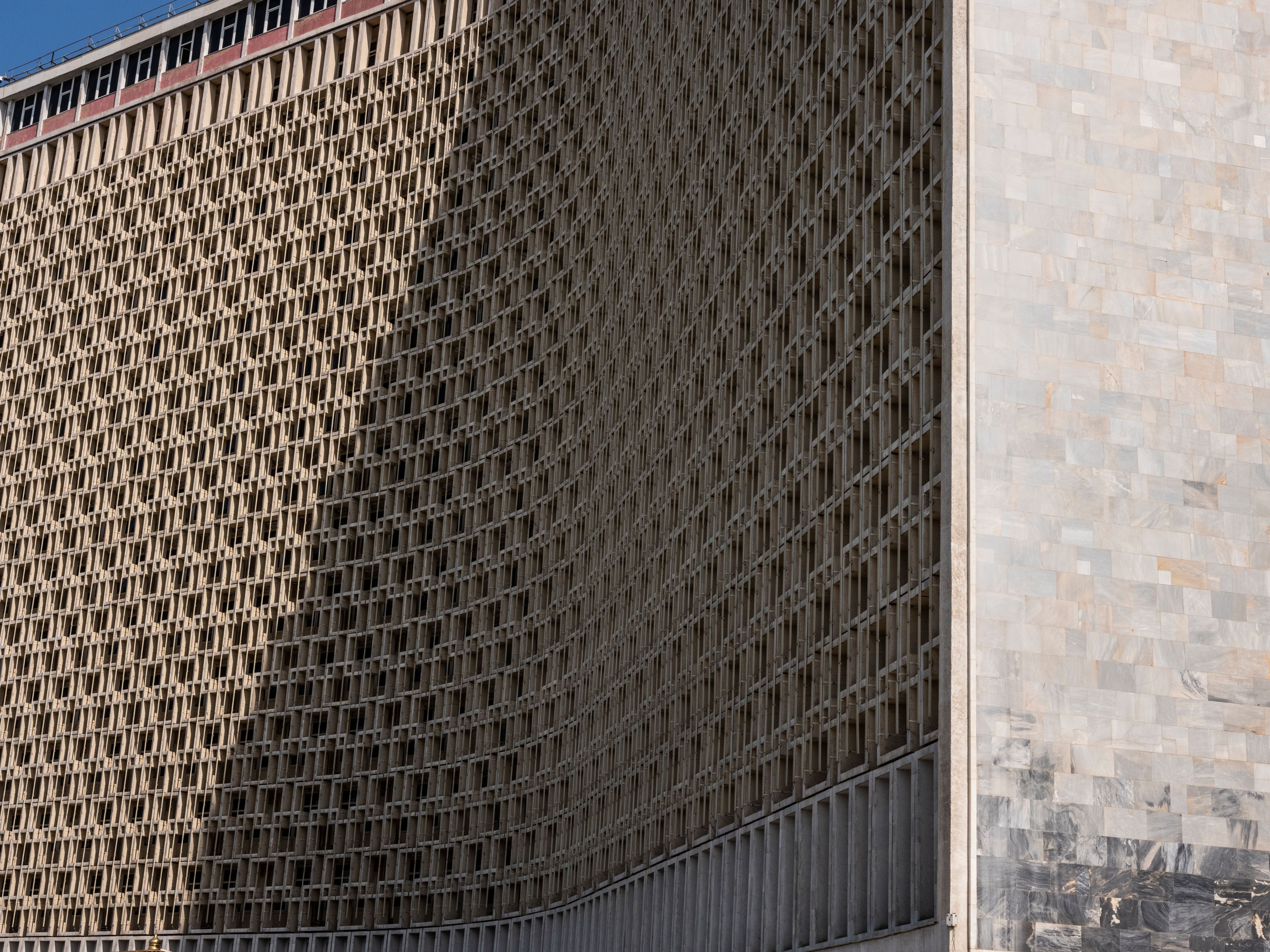

State Museum of History of Uzbekistan, Tashkent, Uzbekistan, 2021, © Armin Linke, Tashkent Modernism. Index exhibition.

Peoples' Friendship Palace, Tashkent, Uzbekistan, 2021, © Armin Linke, Tashkent Modernism. Index exhibition.

In Tashkent in mid-October 2023, the weather forecast announced “smoke” for the third day in a row. Viewed from high-up — the area around the Uzbek capital is mostly flat —, a murky haze obscured the many blue domes and yellow construction cranes that sprout along the perimeter of the city. The top floor of Hotel Uzbekistan, overlooking Amir Temur Square, is an ideal observation point for the old town, the medium-old Soviet-era neighborhoods, the very new high-rises, and the westward avenues towards the city’s mahallas, traditional settlements typically grouped around ponds that create cooler micro-climates in the summer heat. The city has gone through many transformations, and the rebuilding campaign after the 1966 earthquake was probably the most radical. The resulting structures are now being rediscovered, among them the hotel, which was designed to withstand earthquakes. Decades later, the Art and Culture Development Foundation of Uzbekistan — ACDF — brings these buildings to the fore. Tashkent Modernism. Index, was first presented at the Triennale di Milano in the spring of 2023. A conference in Tashkent followed in October, and the exhibition decamped to the Sharjah Triennial this month and will travel to Basel in 2024.

Hotel Uzbekistan, Tashkent, Uzbekistan, 2022 © Armin Linke, Tashkent Modernism. Index exhibition.

For a few weeks in October, Soviet architectural heritage and its preservation took center stage at the State Museum of the Arts. The building itself, with its open galleries that span four stories, served as a case study. Opened in the mid-70s, the cube-like structure sits amid a leafy park; its original gridded façade was clad with fiberglass-filled panels, sealed glass panes that created a soft, diffused light all across the interior. The conference, which assembled architects, practitioners from adjacent fields, historians, and restoration experts, took place on the ground floor, and intended to prepare the city’s modernist buildings for Unesco World Heritage Status.

There is a conspiracy theory in Tashkent: when the earth trembled early in the morning of April 26, 1966, the Soviet authorities seemed a little too ready with a master plan to rebuild the city, a little too eager to raze neighborhoods that did not need bulldozing. Rumor had it that the quake was actually engineered. There is no evidence for this, but it does seem like the Soviet leadership used the occasion to refashion the city in the image of a modern socialist metropolis. “The myth of a Soviet family of nations composed of Russia and its ‘younger’ and less advanced ‘brothers’ is colonialism’s terra incognita,” wrote the historian Greg Castillo on urban planning in Central Asia. The story of modern Tashkent is one about the invention of a Soviet East. Islamic urban life has been reformatted through construction, and the Soviet government resettled nomadic peoples in the course of the First Five Year Plan in the late 1920s.

Under Stalin, Socialist Realism served as the dogma for literature, art, and architecture. Master plans were drawn up accordingly, and former avant-gardists were forced to adapt. While architects found beauty in traditional local ornament, the layout of new cities, with their straight roads and vast plazas, was optimized for mass pageantry, speed, and surveillance. Stalin’s death ushered in more liberal decades and a new interest in experimentation, with architects remembering the utopian attempts of the 1910s and 1920s. Take the Tashkent TV tower, a minaret for the space age by a road that exits the city to the north, or the Chorsu Bazaar, where an enormous concrete dome is covered with blue and turquoise mosaics. By the late 1960s, when the city had been rebuilt, housing blocks were covered in gigantic Timurid tile patterns, and the light baffles of municipal buildings recalled the latticework of mosques and madrasas.

State Museum of History of Uzbekistan, Tashkent, Uzbekistan, 2021, © Armin Linke, Tashkent Modernism. Index exhibition.

Construction of Lenin Museum, now State Museum of History of Uzbekistan, Tashkent, Uzbekistan © Kinofotofond Tashkent, 1969-1970.

State Museum of History of Uzbekistan, Central Atrium, Tashkent, Uzbekistan, 2021, © Tashkent Modernism. Index exhibition.

Tashkent Television Center, façade mosaic by E. Ablin, Tashkent, Uzbekistan, 2022, © Armin Linke, Tashkent Modernism. Index exhibition.

Delegation House of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the USSR, Tashkent, 1975, © Grace, 2022.

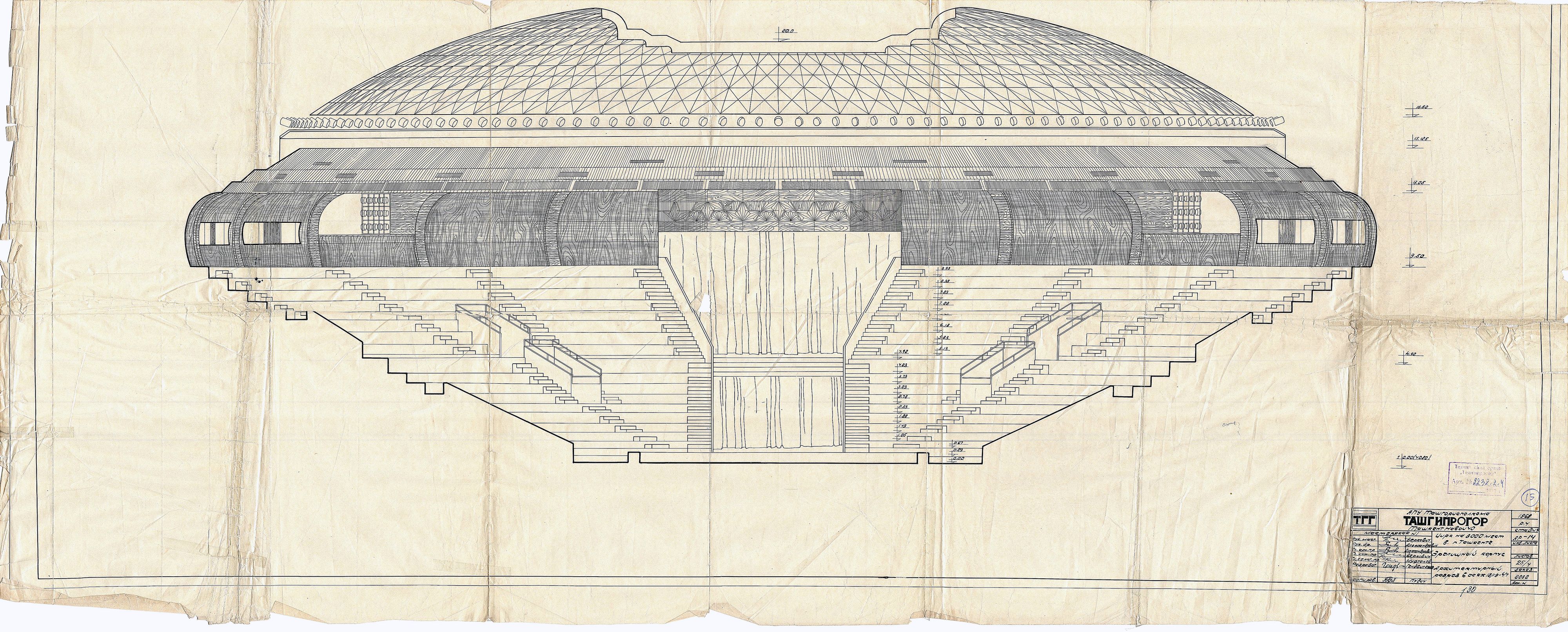

Tashkent was the southernmost metropolis of the USSR, and among the Soviet empire’s biggest cities, each of which had its own architectural typologies. The State Circus, for example, is unique to the city. It looks like a partially submerged, giant UFO, with its azure dome and hefty concrete supports alternating with delicate latticework above ground. The original paint is peeling off, and children play football between the fountains. The Lenin Museum — opened in 1970 to mark the centennial of his birth — is protected from heat and sunlight by cast-concrete screens that reference Islamic architecture. Where its interior once housed a monumental Lenin statue, there is now an empty space, but the temple-like building retains its sacrality. It became a model for Lenin museums in other Soviet cities.

After Uzbek independence in 1991, most of Tashkent’s buildings have not been particularly well-preserved. Treated as relics from the very recent past, one that people preferred to forget about, many structures had been covered up — including the State Museum, which now hides behind a thin front made from Alucobond and glass. Despite its flatness, the cover’s pilasters and arches evoke a classicist exterior. In the 90s and 2000s, when everything Soviet was emphatically rejected, modernist architecture was superseded by a taste for a different, sleek kind of monumentality and representation, which centers glass façades and columns. Much of Tashkent’s modern architecture was ignored, hidden, and destroyed.

On the opening day of the conference, Boris Chukhovich, the architectural historian who works at the University of Montreal and is currently a visiting scholar at the Politecnico di Milano, asked a fundamental question. “How should we name the architecture we are talking about?” The ACDF project chose to go with Modernism, but there is a certain awkwardness about it. The buildings may recall post-war Modern — at first glance they look like distant cousins of Oscar Niemeyer or Louis Kahn — , but with some dating from the 1980s, they’re too recent to fit squarely within Modernism’s accepted timeline. Chukhovich, a slight and soft-spoken man who was born in Tashkent, cautioned against easy categorizations. There is a danger, he said, in perceiving the Uzbek capital as a secondary phenomenon of the Communist world without fully understanding its specificity. “If we didn’t preserve anything from authoritarian regimes, there’d be no history,” said Rem Koolhaas on the second night of the conference when questioned about the merit of saving Soviet architecture. His keynote positioned preservation as a fundamental aspect of Modernity: it “coincides with revolutions,” as if it was, in itself, a motor of history rather than a way to simply conserve it.

Tashkent State Circus, project section © Tash Giprogor, 1975.

The ACDF came up with a list of 40 buildings in Tashkent, 15 of which are now filed for preservation. The strategy distinguishes between significant elements that should be kept, parts that can be modified, and features that need to be recovered — like the exterior of the State Museum. Many of the buildings are still in use, such as the residential building nicknamed Zhemchug — “the pearl” — after a shop that used to occupy the ground floor. Made from monolithic concrete, its architect, Ophelia Aidinova, conceived the building as a vertical mahalla with small, village-like units stacked on top of each other and verdant suspended courtyards on every third level. The construction was not cheaper or faster as the architect had promised, but the inhabitants were quick to appropriate the common areas, adding rooms, balconies and brickwork to their apartments. Questions of authenticity and conservation call for answers that go beyond restoration. Koolhaas claims to be a firm believer in the authentic, but then again, he is also the architect who wrapped a 1960s restaurant in Moscow’s Gorky Park in polycarbonate to create The Garage Museum of Contemporary Arts. With Koolhaas, there is no concept that can’t be turned against itself. “We have to allow components to relearn their own authenticity,” he adds.

The effort to preserve Soviet Modernism in Tashkent is not the only endeavor of the Art and Culture Development Foundation. Established in 2017, the foundation aims at international cooperations, among them the touring exhibition around Tashkent Modernism, but also a show of pre-Islamic Uzbek artifacts in Berlin and representations at the Venice Biennial. The foundation is eager to represent the country’s culture internationally, presumably to fashion a position between Russian and Chinese claims to power. “Our long-term strategy at the ACDF revolves around a holistic approach to cultural preservation and education,” Gayane Umerova, the head of the foundation, told me over email. “We aspire to create a legacy that will endure, enriching the lives of generations to come.” Local interest has shifted, Umerova remarks. “We seek to foster a sense of pride and awareness among the people of Uzbekistan while building bridges of understanding and appreciation with the international community.”

Panoramic Cinema under construction, Tashkent, Uzbekistan © Sutyaghin family archive.

Theater Arena, Tashkent, Uzbekistan, 2021, © Armin Linke, Tashkent Modernism. Index exhibition.

When I stepped out of the State Museum and onto the intersection, the area felt a little disjointed. The city is generous with space, a legacy of Soviet urban planning; the blocks are separated by wide boulevards and traffic hums ceaselessly, yet it feels almost calm. Closer to the city center, the panel-constructed blocks lining the roads are interspersed with intricate pre-revolutionary brick buildings and a contemporary hybrid of classicism and Orientalism — think tapered Khivan columns and mirrored windows. Within this, Modernist buildings are neither isolated nor out of use, but they tell the story of a forgotten urbanist vision.