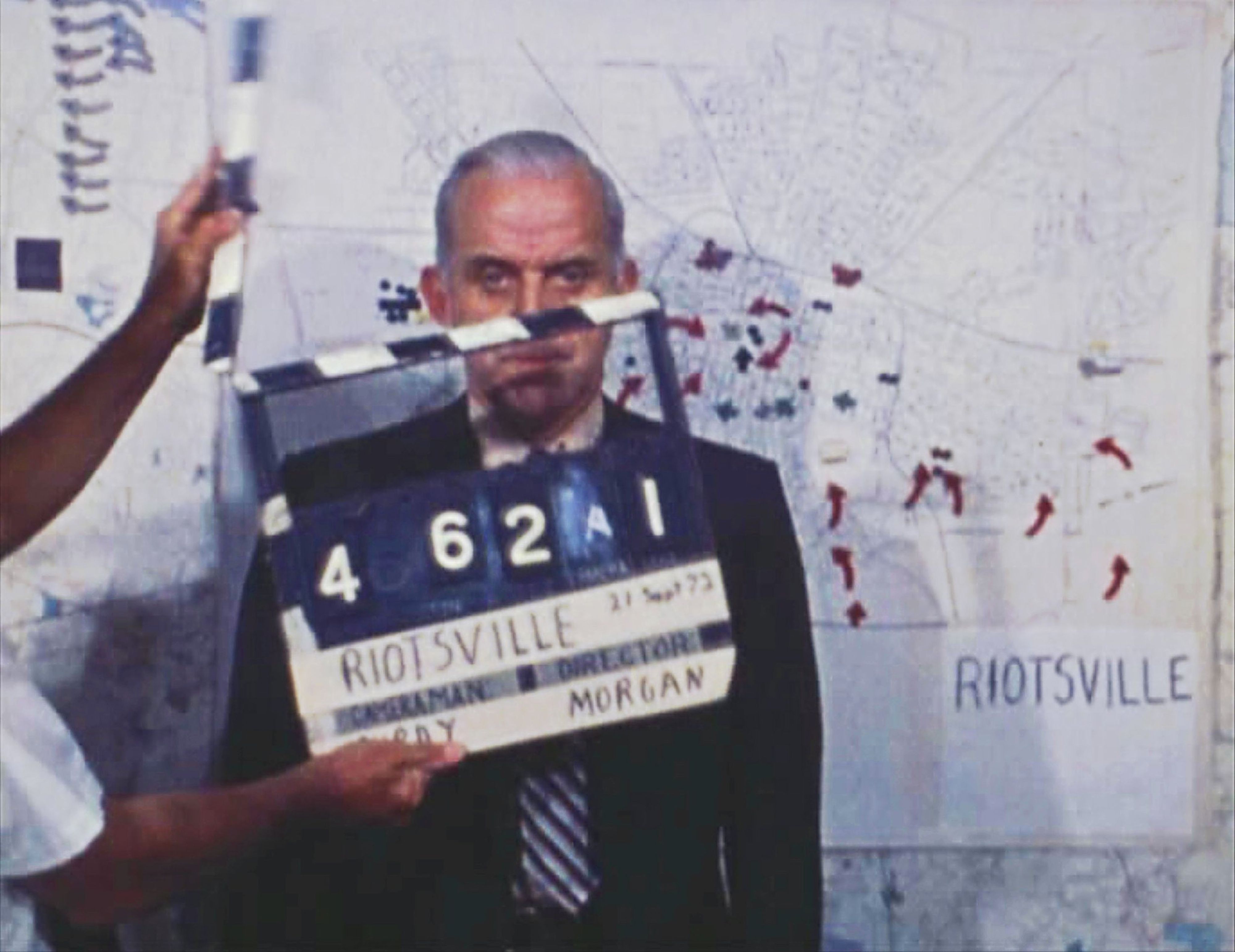

A scene from Riotsville, USA. Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures.

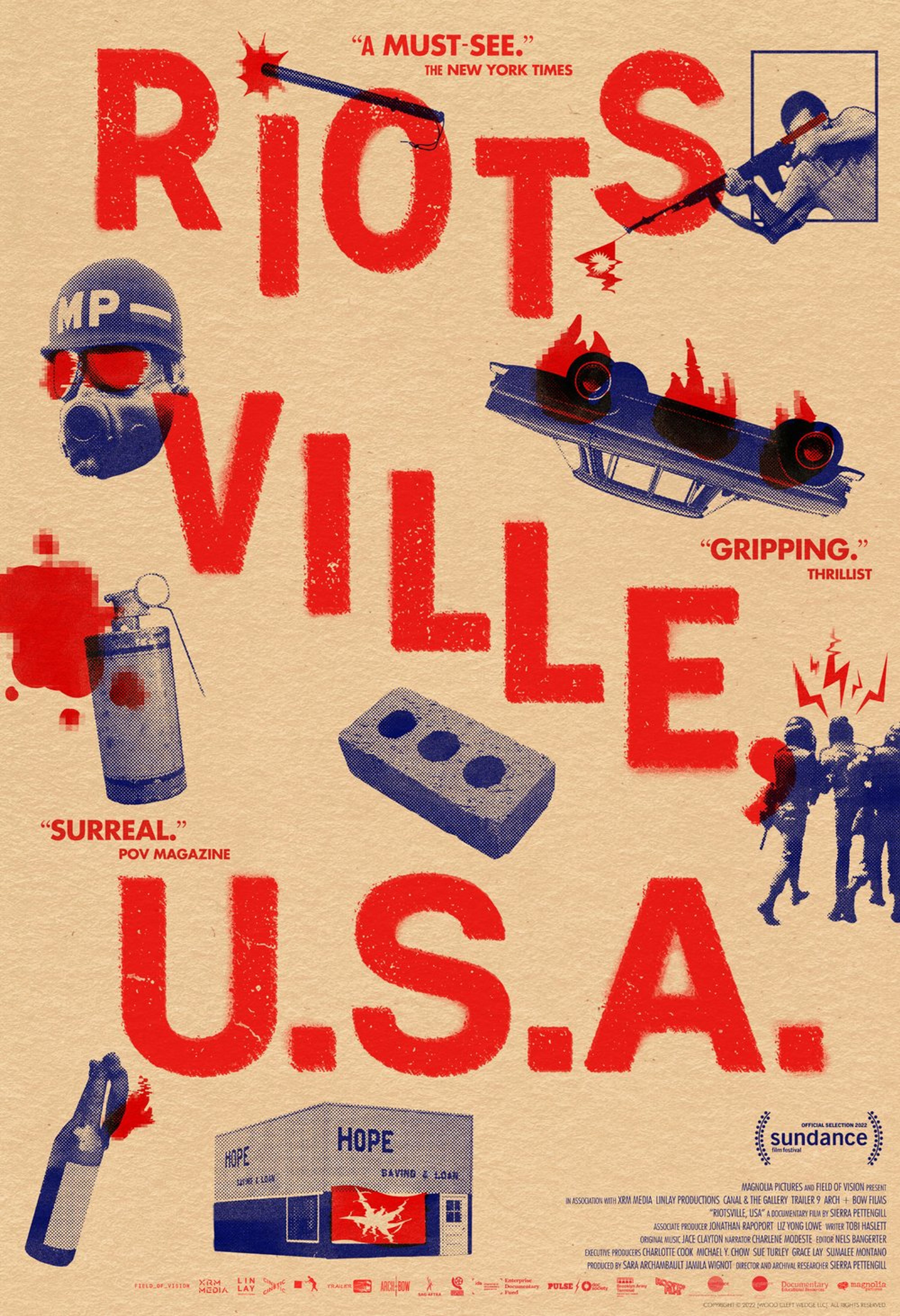

Theatrical one-sheet for Riotsville, USA. Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures.

Riotsville, USA is an archival film that explores the historical phenomenon of riotsvilles, simulated towns built on American army bases in the late 1960s to train police and soldiers in “riot suppression” through choreographed reenactments. Director Sierra Pettengill worked collaboratively with a team that included Tobi Haslett, who wrote the film’s voiceover, Charlene Modeste, who performed it, editor Nels Bangerter, and musician Jace Clayton to carefully unpack the historical context of police militarization in the 1960s. In the process, she challenges any sense of historical inevitability while also criticizing television and film media’s role in supporting government narratives. Ahead of the film’s opening at Film Forum in New York last week, Pettengill spoke on the roots of police repression, violence as represented in nonfiction and the limits of material history.

A scene from Riotsville, USA. Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures.

PIN–UP: Riotsvilles were part of a series of programs that America pursued in the wake of the rebellions of the late ’60s that gradually led us to an increasingly militarized police force. You emphasize that this is public history. Why is that important?

Sierra Pettengill: I think there is something reassuring to audiences to find out that something was secret and that we had no way of knowing. I think there's a kind of self-soothing that comes with that idea, as opposed to a public history that played out on television and for obvious reasons has been wiped from the greater cultural narrative. The Kerner Commission report [issued in 1968, which attributed the riots to a lack of economic opportunity and suggested anti-poverty programs but was largely ignored by policymakers] was a bestseller. That it’s news to a lot of us is a telling story about the lessons we’re determined not to learn. The New York Times was reporting on riotsville in real time. Half of the footage of riotsvilles is from ABC and BBC.

Besides the material from broadcast news, much of the material in the film was shot by the US Army and did not exist digitally until you requested it from the National Archives, sight unseen. What was your first reaction to these images?

When I look at the final film, a lot of the moments in that footage that first struck me have wound up there. I worked with an incredible editor who followed his own instincts, but the things that really struck me at the beginning stayed too. It’s this mix of absurdity and deep, dark violence. Everyone in riotsville is a soldier dressed as protestor, and there’s a moment where a Black soldier [dressed as a protestor] is getting arrested and howling and being physically shoved into a tank. The cut to the audience of white men, some of whom are literally smoking cigars, laughing, is deeply chilling. It’s a very quick reversal: at first it seems silly, and then you see how this might actually play out. It became a kind of driving force in the film to make sure that this feeling of absurdity is experienced by the audience as indicative of the callousness of the people in power.

A scene from Riotsville, USA. Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures.

A scene from Riotsville, USA. Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures.

You are very careful about what images you show, and in what sequence. What sort of ethics are you proposing in working with this footage?

We were very deliberate about what images are in the film and what images are not. There was originally an idea that we would show no footage of riots. It's very necessary that we cover [protests during the 1968 Republican National Convention in] Miami in the way we do, to show the real-world application of this. I didn’t want it to exist in some sort of abstract fantasy. But we put that footage at the end as a way of countering the government’s narrative structure, that there is a set of protests and then police repression is the reaction. In this film — and in America — police repression is what results in protests. The structure of the film is very deliberate in that way.

I was hesitant to put protest footage in the film in part because the film is about a repressive apparatus, and I don’t think it does justice to the vitality of those movements and the conditions under which those films were shot. It didn't seem fair to be pairing them with this deeply violent state imagery. That work deserves its own proper appreciation and context. It’s hard to work with material that is so implicitly and explicitly violent, and a lot of work went into not repeating the harms of the original footage. That's why the onscreen text and the voiceover are so important, to undercut that as much as possible.

A scene from Riotsville, USA, a Magnolia Pictures release. Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures.

There’s a larger recalibration occurring around how violence gets represented in nonfiction film. Where do you hope this conversation is headed?

I think that is a really important conversation and it’s ever evolving. It really is a case-by-case thing and has to do with how it’s used and who uses it. As a white filmmaker especially, it doesn't feel like [footage of the 2020 protests] is my territory to be working with, for example. A lot of Riotsville, USA covers white people with power, but also the way their thinking trickles down to the [white] population: the middle-aged housewives in Michigan who are target shooting and the volunteer riot posses in Chicago. It’s the preparation for violence and how that moves its way either top down or through society. In terms of this film, the goal was to show the threat and practice of white violence without needing to subject a Black body to it.

A scene from Riotsville, USA, a Magnolia Pictures release. Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures.

You were working with archival footage that has its own material history and limitations, which gets mentioned in the film. How did you work within those limitations?

I wanted the film to feel like the process of going through this [material] and trying to figure it out. And call attention to the holes in the archive. The Liberty City organizing meetings [for those protesting the 1968 Republican National Convention] are silent. Oftentimes when you're working on a film, if footage is silent, it's like, “Oh well, I guess we can’t use it.” That’s one way that absences in the archive can be become absences in the narrative, and I’m trying to work with that and against it in this film. I was also influenced by Hito Steyerl and the idea of the traces that digital material takes with it. It was important to remind us that we’re in 2022 and we’re looking at this from a distance. I didn’t want it to feel immersive, like you’re transported back to 1968. I wanted to show how the digital traces of this footage remind us of the systems that it’s passed through to get to us. We point out which footage is public domain. Archival films are really expensive to make, as most of these archives are corporately owned. So some of the footage that we wind up with that’s fair use is really bad quality. I wanted to lean into that, making the material conditions of the making of the film visible.

The final shot of the film is a long a zoom into an image, until we just see the pixels. Is that what you're getting at?

I like to leave the ending open; it’s meant to be an invitation. By visually going to abstraction there, getting close to something and just seeing a lot of gray, you create imaginative possibility. It’s not like you get down to the core of things and that’s the end of the work. That’s an image of a city, a territory that needs to be open for all of us for imaginative possibilities.