Detail of Sabine Marcelis and OMA’s collaboration on the Repossi flagship store in Paris. Photo by Cyrille Weiner. Courtesy of Studio Sabine Marcelis.

Sabine Marcelis photographed by Ari Versluis for PIN–UP

Sabine Marcelis’s studio is on the second floor of a no-frills former energy factory in an industrial neighborhood in the port of Rotterdam. It’s a decidedly unfussy choice of location for the athlete turned designer, whose elegant candy-hued resin pieces have burned up both the collectible market and the millennial design feed over the past few years. Their glossy sheen in sweet pinks, mints, and glowy oranges belies the hard work that goes into their creation. A self-described “production nerd,” the 36-year-old Eindhoven graduate is most at home with rolled-up sleeves in the workshop, which she shares with her friend and producer Sotiris De Wit. Marcelis and her team will spend weeks perfecting the density and statics of resin, her favorite material, alongside glass, the substance she works with most. The resulting pieces, inspired by the elements air, light, and water, defy strict typologies of furniture design: resin pieces that function as tables, stools, or sculptures, and glass designs that straddle the line between light source, art piece, and mirror. Thanks to her sense of color and understanding of space, her projects are also starting to defy the scale of conventional design, encompassing fashion, interiors, architecture, and outdoor lighting sculpture. Since starting her studio ten years ago, Marcelis has now become an indispensable part of Rotterdam’s vibrant scene of designers, artists, and architects. And they are lucky to have her, because it almost didn’t happen. Her initial destiny was sport — it was a health issue that cut her snowboarding passion short, leading her to follow her creative instincts.

Detail of Sabine Marcelis’s Shapes of Water/FENDI Fountains, 2019. Made from resin on travertine plinths. Installation commissioned by Fendi for Design Miami. Photo by Carl Kleiner. Courtesy of Studio Sabine Marcelis.

Felix Burrichter: If the title of this story was “Sabine Marcelis: Snowboarder Turned Designer,” would that be accurate?

Sabine Marcelis: I guess so yes, but my snowboarding career wasn’t as successful as I would’ve liked it to be. So maybe: “Aspiring Snowboarder Turned Designer: From the Slopes to the Workshop”— that would be the headline.

There seems to be some confusion — where are you from?

A lot of people think I was born in New Zealand and then immigrated to the Netherlands, but it’s the other way around. My parents are somewhat nomadic and restless. When I was ten, they decided to move the entire family to the other side of the world. They’d never been to New Zealand and wanted to go on an adventure.

Where in New Zealand did you live?

In the North Island countryside, near the beach. The mountain for skiing was three hours away, but in New Zealand that’s nothing. We would drive there in the morning and come back at night. You have a different idea of distances in New Zealand, very different from people in the Netherlands. I think it’s a good mindset to have — that the world is not so big.

Detail of Sabine Marcelis and OMA’s collaboration on the Repossi flagship store in Paris. Photo by Cyrille Weiner. Courtesy of Studio Sabine Marcelis.

Detail of Sabine Marcelis's Totem Light for Side Gallery, 2019. Made from resin and neon (+transformer). Photo by Pim Top. Courtesy of Studio Sabine Marcelis.

How did you get into snowboarding?

I got to choose where I went for my last year of high school, and opted for a skiing town in South Island. It was an outdoor-pursuits college, so you could take snowboarding, rock climbing, and kayaking as subjects. It was a very alternative school. Between the ages of 16 and 21, I was snowboarding, doing back-to-back winters between New Zealand and Mammoth, California. I also spent a season in Whistler, Canada. And then one day I got sick — my appendix exploded, and it was very bad. Several surgeries. It was horrific. I survived, but it was scary. I fell into a crisis. Do I really want to be snowboarding? It was such a big part of my life since I was 14, so when I stopped I was really lost. And then I remembered that when I was younger, I was always super creative. I used to make and sell my own jewelry, and I would make bags and jewelry and sell them next to my parents’ flower farm stall at the market.

Your parents were flower farmers?

Yes. They grew and sold flowers. We lived on a big piece of land and they built a greenhouse where they grew the flowers. They mostly grew chrysanthemum

and celosia — they’re the ones that look like brains. They did that for a while, then they stopped.

Did you like growing up on a flower farm?

I did. Next to the greenhouse there was also a kiwi fruit orchard. As kids we always helped a lot with picking the kiwi fruit. We were definitely put to work.

Sabine Marcelis, Boa Pouf for Hem. Made from wool, nylon, PU foam, and wood. Courtesy of Studio Sabine Marcelis.

Sabine Marcelis photographed by Ari Versluis for PIN–UP

Sorry, we got sidetracked with the flowers. Tell me how you ended up in design school.

My sister had just finished studying industrial design in Wellington and suggested I stay with her for a bit. It looked like fun, so I thought I’d try it too. My first-year tutor was Lee Gibson, who is now the footwear design director of the Nike Jordan brand in Portland. He’s a very inspiring person. But after two years of industrial design in Wellington I needed a new challenge. So, during a trip back to the Netherlands, I also visited Design Academy Eindhoven. It felt very free and interesting, so I applied and got accepted. It was a bit of a culture shock, because in New Zealand the teachers hold your hand and guide you through the curriculum — you can make everything at the school, and you’re surrounded by other students the whole time. In Eindhoven, it was much more like real life: you have a meeting with your teacher, they give you advice, and then you don’t see them for a week. You’re left to your own devices a lot. And that gives you freedom to do what you want to do. I also learned very quickly that if you have ideas that you cannot physically make yourself, you need to partner with companies, specialists, or fabricators. And that’s the basis of creating work in the real world.

What were your plans once you were done with college?

I was determined to get my own studio because I didn’t want to have a boss or anything like that. So, the moment I graduated, I canceled my lease in Eindhoven and moved to Rotterdam, where you could get an antikraak house. Kraaken means squatting, and antikraak was a policy where the city would rent empty real estate very cheaply so that people wouldn’t squat it. I think I paid 150 euros a month for a four-bedroom house. But it also had a downside — the city could kick you out at a week’s notice. That first year I moved four times, after completely renovating each of those houses every time. But it allowed me to have my own studio space, even if I had no work. I would just go there every day and be like, let’s get to work. [Laughs.]

Sabine Marcelis, SOAP table for Etage Projects. Made from semi-polished acrylic polyester resin. Photo by Pim Top. Courtesy of Studio Sabine Marcelis.

What kind of projects did you eventually work on?

I’m a nerd when it comes to production methods, and I know how a lot of things are made. As a result, my friends would ask me to help them out with production or product development, especially for fashion accessories.

Did your love affair with resin begin then?

I had already worked with resin before, but it was the cube shape that made it magical. The slight translucency in the corners makes it seem lighter — it starts to have this glowing effect. Resin is an amazing material to manipulate. It can be completely transparent, completely opaque, polished, reflective, matte... I still haven’t found its limits. The reason I’m a designer is to find those. I like to trap myself in situations where I have to deliver — if I don’t I let someone down. So you just have to find a way, and I really love that challenge. I like a good deadline, figuring it out together with the team. It’s a bit of a game.

Top: Sabine Marcelis, Candy Cube for Side Gallery, 2017. Made from high polished polyester resin. Photo by Titia Hahne. Bottom: Sabine Marcelis, SOAP table for Etage Projects, 2020. Made from semi-polished acrylic polyester resin. Photo by Pim Top. Both images courtesy of Studio Sabine Marcelis.

Top: Sabine Marcelis, Stacked Fountain for Etage Projects, 2022. Made from resin and metal steel on a travertine plinth. Photo by Titia Hahne. Bottom: Sabine Marcelis, SOAP column for Etage Projects, 2020. Made from polyester resin. Photo by Titia Hahne. Both images courtesy of Studio Sabine Marcelis.

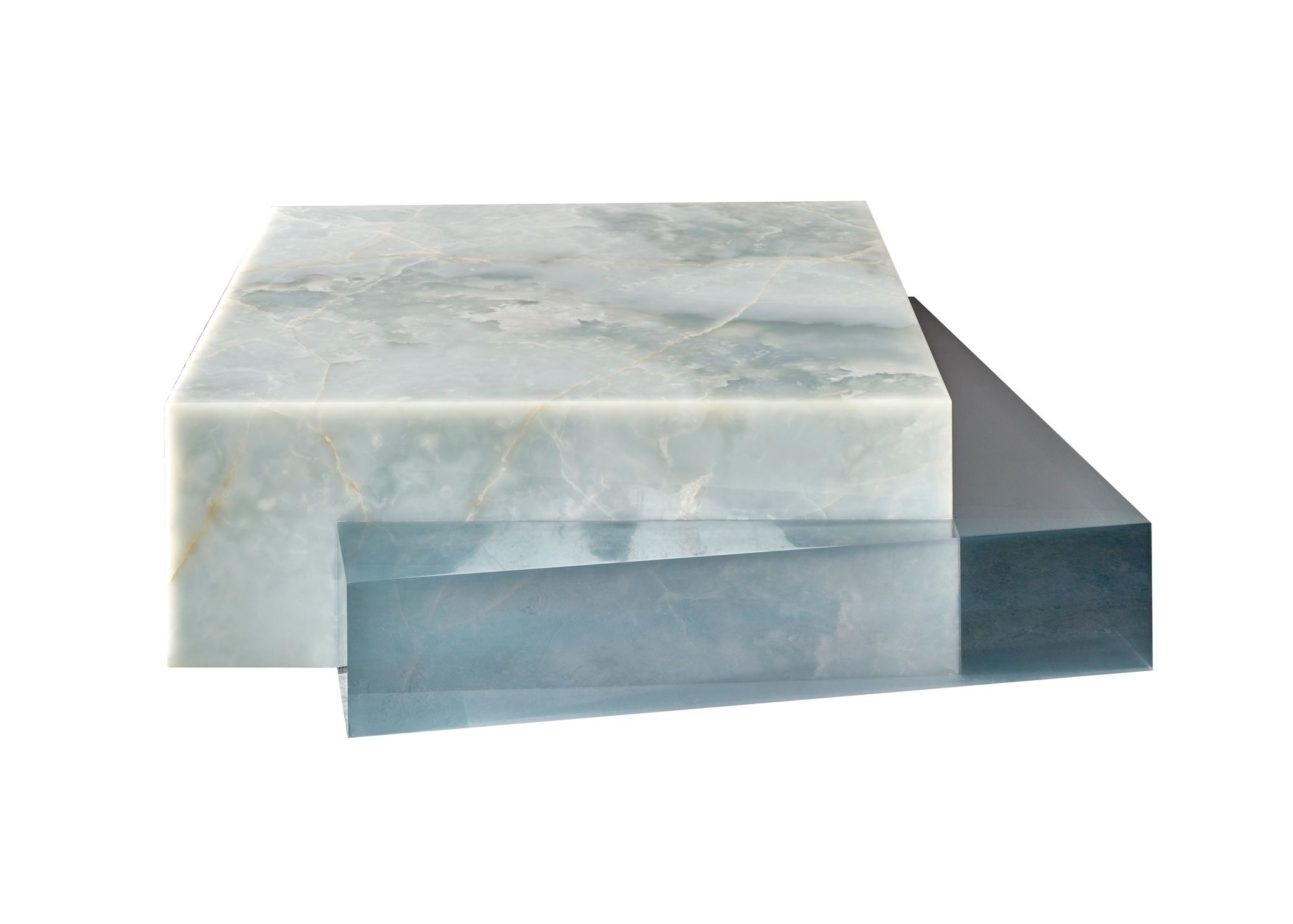

Top: Sabine Marcelis, Stacked Fountain for Side Gallery, 2019. Made from high polished resin and onyx. Photo by Pim Top. Bottom: Sabine Marcelis, Totem lamps for Side Gallery, 2019. Made from resin and neon (+transformer). Photo by Pim Top. Both images courtesy of Studio Sabine Marcelis.

There’s an important architecture legacy in Rotterdam, and I’m specifically thinking of those remarkable resin models Vincent De Rijk made for OMA in the 1990s and early 2000s. I see that lineage reflected in your work.

Oh yes. Sotiris De Wit, my production partner, used to work for Vincent De Rijk. Vincent is amazing, and I actually first approached him to make the cubes. He wasn’t available, so Sotiris stepped in. We eventually combined our studios in the same building because we were on the phone all day long to each other. This is a lot more practical: I’m upstairs, he’s downstairs with his company S.T.R.S.

Some of my favorite projects of yours are your spatial installations, where you directly engage with the architecture. Does the proximity to Rotterdam’s architecture scene have anything to do with that?

For sure. You’re always a product of your surroundings. Before coming to Rotterdam, I didn’t know much about architecture. But it’s a small city, and I always knew architects who were working at OMA, like Ippolito [Pestellini Laparelli, now of 2050+], who asked me to work on the Repossi project in Paris. And then obviously also being with Paul [Cournet, Marcelis’s life partner, who spent eleven years at OMA before founding design and architecture studio CLOUD]. I’ve learned so much through him and from other architect friends. I’ve also been fortunate not to be pigeonholed into a specific scale of design. I love it when people see opportunities for me to do things in different scales, and in fields that I’m not necessarily trained to work in.

OMA came to Sabine Marcelis in 2016 to collaborate on the Paris flagship of jewelry brand Repossi. Marcelis experimented with resin to create varying degrees of transparency throughout the space. Photo by Cyrille Weiner. Courtesy of Studio Sabine Marcelis.

Over the store’s three floors, she also created various layers of glass, mirrors, and aluminum — playing with transparency, color, and reflectivity in conversation with the architecture and the jewelry on display. Photo by Cyrille Weiner. Courtesy of Studio Sabine Marcelis.

The Dutch Pavilion you designed for the 2017 Cannes Film Festival is a great example. Can you tell me more about it?

At Cannes, every country has its own pavilion where business meetings are held. They’re never very sexy spaces — just a tacky tent on the beach with some sofas and a fridge. The Dutch Nieuwe Instituut teamed up with the Eye Filmmuseum in Amsterdam and approached me for the project. The brief was to celebrate 100 years of De Stijl, the Dutch Modernist art movement, but to also create a functional meeting room. So I just looked at it as an extruded Mondrian painting, but with Maarten van Severen and [Gerrit] Rietveld sofas to sit on. Entering, you saw flat planes of color against a white background, but as you walked through the pavilion you discovered that these planes were in fact three-dimensional volumes, and that there was a gradient in color saturation that allowed for a certain transparency. That project was the first time I realized you could make a hybrid of object and space.

Is there a hybrid quality to your work in general?

My designs are usually elementary or minimal shapes. The cube, for example, was initially designed to be a podium for fashion accessories, but then found its way into all these different contexts. Lorde even used it during her tour as a stage prop. I love it when the work is not overly specific. There’s an ambiguity that leaves space for interpretation. That’s also the reason I don’t write massive texts about my work — it’s usually just a short description. If people see other things in it, that’s more interesting for me.

A key project exhibiting Marcelis’s work with architecture and space was her 2017 Dutch pavilion at the Cannes Film Festival, which extruded De Stijl paintings into three dimensions by playing with perception and perspective using simple gestures of colored glass and metal supports. It’s reminiscent of the 1960s Light and Space artistic movement, and it anticipated her 2021 update to the research center at Het Nieuwe Instituut in Rotterdam, in which she used reflective gradients and subtle transparencies to lighten up the space and its custom USM furnishings. Photo by Lothaire Hucki. Courtesy of Studio Sabine Marcelis.

Do you find there are common misconceptions about your work?

I think people sometimes expect me to have a grand plan, or that I have some sort of color theory. I don’t. I work from intuition and from things I like or that fascinate me. But generally I’m not that interested in what other people think. I once received an internship request from someone who wrote, “It’s obvious you know a lot about the occult, and I want to learn from you.” [Laughs.] That was probably the biggest misconception of my work.

When I interviewed Konstantin Grcic a couple of years ago, he said he used not to have a sofa in his house, and had never really designed sofas either. But then he had a baby, and felt compelled not only to buy a couch but to design one too. Has becoming a parent also changed your approach to design?

It sounds clichéd, but it does put things into perspective. Suddenly there’s someone else with a longer future than your own to consider. You wonder, “What is he going to think of the material choices I’ve made?” That’s why we’re keeping the resin pieces very limited, and they’re also expensive, so they require serious consideration for someone to purchase them. Hopefully they’re something very special and unique that will be passed down through generations. They should never be in mass production. At the same time, we’re doing a lot of research into alternative materials. At first, I was very worried because I thought I was never going to be able to work in a similar way as I’ve been able to with resins. The challenge is always the translucency, because a lot of bio-based resins are opaque. You lose the whole play of light. We’re working on resolving that, and we’re now finding new biomaterials that are completely circular in their production process. Not a lot of people have worked with them yet — we aim to be at the forefront of using those.

Sabine Marcelis, Boa Pouf for Hem. Photo by Titia Hahne. Courtesy of Studio Sabine Marcelis.

Speaking of materials, let’s talk about No Fear of Glass, your 2019 exhibition at Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Pavilion. What is your relationship to that space? Was it the inspiration for the pieces, or did they already exist?

The space came first. Luis [Sendino from Side Gallery] asked me what my dream project would be in Barcelona, and I said, “A solo show in the Mies van der Rohe pavilion.” It was almost a joke, but he made it happen. I was a bit shocked. It’s such a beautiful, perfect space, so the project was daunting to me. In the end I approached it similarly to the Cannes pavilion, by extruding material — a combination of travertine pulled up from the ground and the marble and glass pulled out from the sides, and together they form the chaises longues. The only curve in the pavilion is found in the Barcelona chair, so that informs the functional pieces, which are all curved. And the water fountain also plays a big role. It was so difficult to make — nights and nights of despair! But there was a deadline and it had to work, even if that meant pushing the limits of what’s possible.

Marcelis created the installation No Fear of Glass (2019) in response to the architecture of Mies van der Rohe and Lilly Reich’s 1929 Barcelona Pavilion. Inspired by the Barcelona Chair, Marcelis crafted two chaise longues using arcs of colored glass set in travertine, the same material as the pavilion’s floor. Photo by Tim Top. Courtesy of Studio Sabine Marcelis.

While the architect had supposedly been instructed to not use too much glass, Marcelis makes that material the main focus. Photo by Tim Top. Courtesy of Studio Sabine Marcelis.

I understand that the title of the show was inspired by Josep Quetglas’s 2001 book about the Barcelona Pavilion, Fear of Glass. What makes you unafraid of glass?

I’m well-known for my resin work, but most of my production is actually in glass. So for me, in my studio, there is no fear of glass. At the same time, I was absolutely intimidated by the space of the Barcelona pavilion.

It seems to be the way you approach projects in general: conquer your fear by just forcing yourself to do it.

Yes. It’s like doing an extreme sport. I had never worked on a project that has so much legacy and so much emotion in it already. I had also never done a project that upset anyone. I knew people would have strong opinions about the Barcelona Pavilion. While we were setting up, several tourists stopped by, trying to enter, and even confronting us about what we were doing. Comments like, “This doesn’t belong here!” “Take it away.” “Don’t you have any respect?” I’m more used to only positive responses.

Sabine Marcellis's Barcelona Pavilion installation, No Fear of Glass, 2019. Photo by Tim Top. Courtesy of Studio Sabine Marcelis.

Tell me about your current exhibition Color Rush at the Schaudepot, Vitra’s public archive of design pieces.

Yes, the Schaudepot presents a sort of timeline evolution of the history of design. But, instead of sorting the history of design chronologically, I’ll be doing it by color. It’s a new way of looking at the collection, juxtaposing designs from all decades directly alongside one another and comparing how a particular color was applied in different eras. Is it in the material? Is it applied to the material? How has it aged? What material was used?

Did you get your sense of color from growing up on a flower farm?

Not really. I would say my sense of color comes from spending time in the mountains. The best colors occur when you are above the clouds. At sunset, when the clouds and the sun mix, you get the most insane combinations. How do you harness this ephemeral moment in a permanent object? That’s the question I always ask myself. I was also always fascinated by how snowboard

goggles can alter the way you experience space. If it’s a sunny day, you put on the reflective goggles, but if it’s a white-out day and you can’t see any depth of color, you put red lenses on. It’s interesting how you can manipulate your experience of space through color.

Detail of Sabine Marcelis’s Shapes of Water/FENDI Fountains, 2019. Made from resin and travertine plinths. Installation commissioned by Fendi for Design Miami. Photo by Carl Kleiner. Courtesy of Studio Sabine Marcelis.

Sabine Marcelis, Mirage, 2021. Made from glass mirror. From Gallery COLLECTIONAL's inaugural show, The Shape of Things To Come. Photo by Rami Mansour. Courtesy of Studio Sabine Marcelis.

Sabine Marcelis, Gradient mirror, 2019. Made from glass mirror. Photo by Pim Top. Courtesy of Studio Sabine Marcelis.

In addition to the pieces you make with Etage and Side gallery, you also work with industrial design companies. cc-tapis, Established & Sons, HEM, Arco, IKEA... who else?

That’s it.

That’s actually less than I thought.

It’s not necessarily the direction I want to go in. The thing that excites me most about being a designer is figuring stuff out myself. When you work with a company, they will do that for you. It’s a luxury but it also means I miss out on the part of the design work that I find the most rewarding. I’m also pretty good at understanding the intent behind a collaboration. I’ve had meetings with brands where they’ve essentially already designed the project. And that’s when

you wonder, “What do they still need me for? Or do they just want a copy of something I already did in the past?”

Sabine Marcelis, Stroke 1.0 for cc-tapis. Made from wool. Courtesy of Studio Sabine Marcelis.

Your work with IKEA stands out because it’s such a ubiquitous brand. What got you interested in the project?

I often get requests from people who like my work but it’s way over their budget. Most of the time, I can’t even afford my own work. I liked the challenge of making something accessible but without losing the soul of my more expensive work. How does the materiality change when you think about mass production? The first design I did was a lamp with a slash in it, very simple — just a single sheet of metal with an LED behind it, doing all the work. After that the IKEA team asked me if I would be interested in doing a full collection of lighting, glassware, tableware, and rugs, which is coming out this fall. During the process I developed so much respect for them and it’s taught me so much — about sustainability, about packaging, but also about making things attainable throughout the world.

The quintessential piece that every designer wants to do is a chair — it’s considered the holy grail for architects and designers.

Not for me! I haven’t yet thought of a fantastic, brilliant idea for a chair. So, until then, I don’t think the world needs a chair from me.