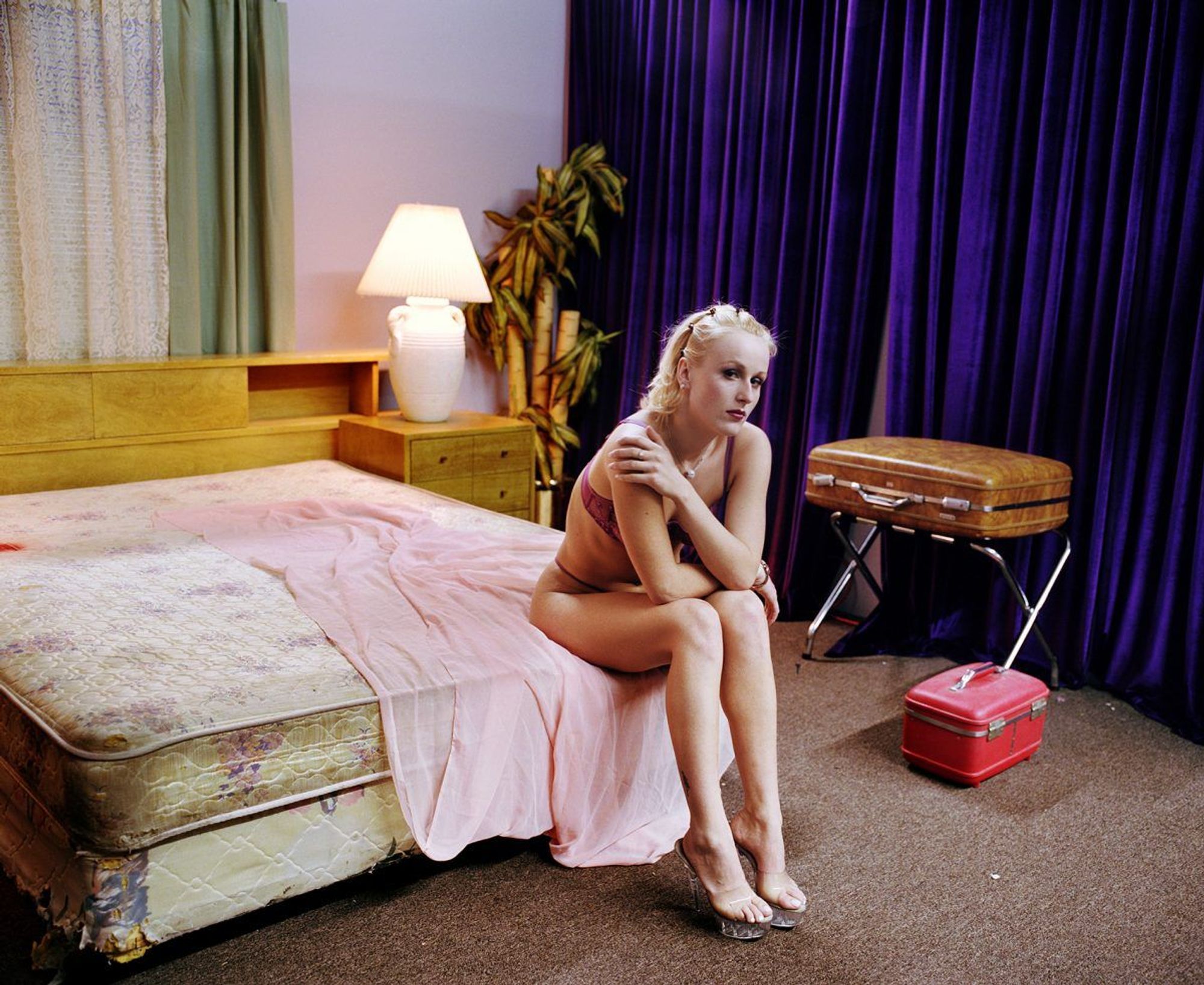

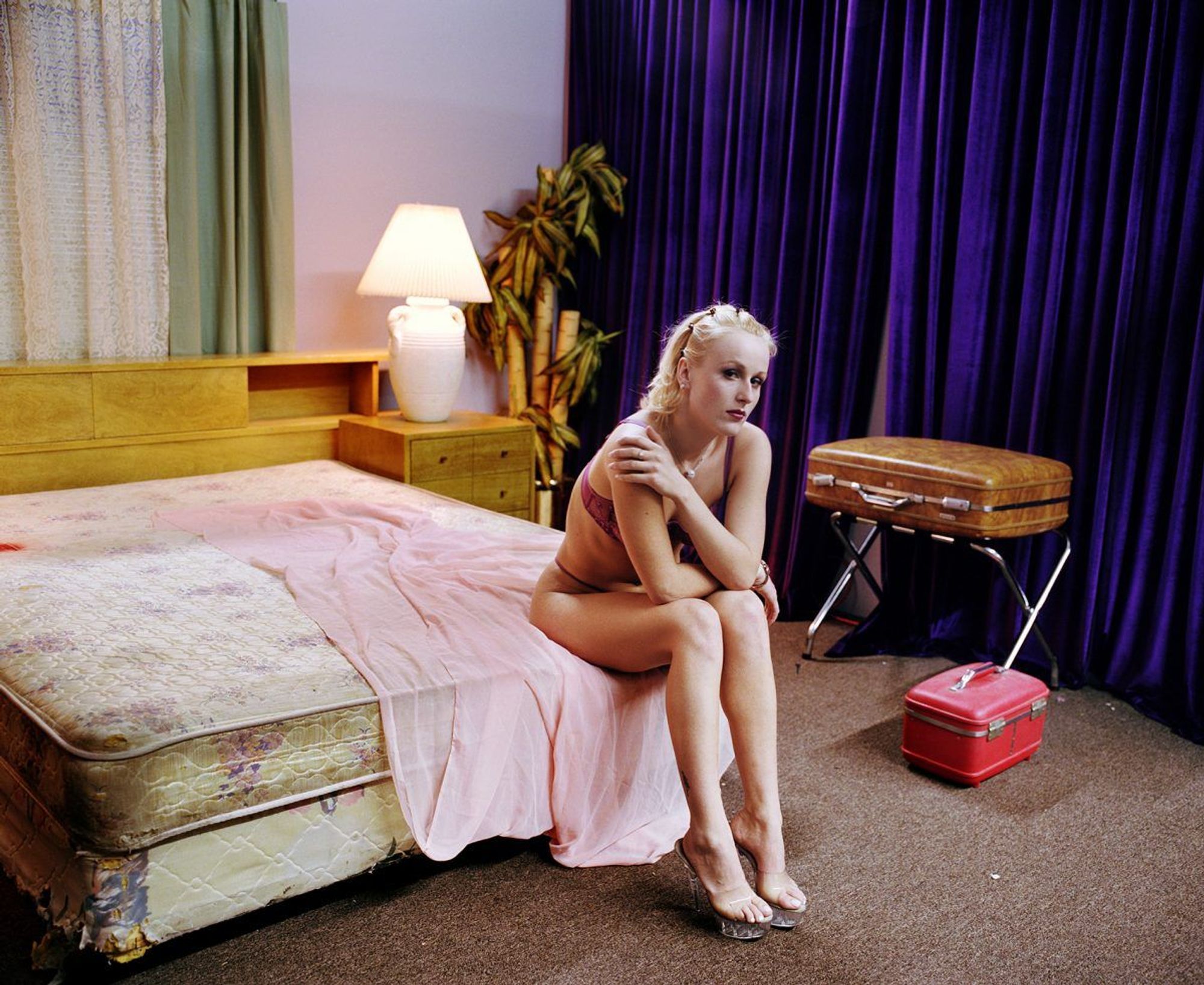

Larry Sultan, Sharon Wilde, 2001. © Estate of Larry Sultan. Courtesy Casemore Kirkeby, San Francisco; Yancey Richardson Gallery, New York; Thomas Zander Gallery, Cologne.

Film still from the movie Pleasure by Ninja Thyberg. Courtesy Neon

About an hour into Pleasure, Ninja Thyberg’s graphic, deeply unsensual 2021 film about the adult movie industry (now released in the U.S.), a pair of fledgling porn stars are shown hiking in the Hollywood hills with the intent of seeing the Hollywood sign. Bella, a nineteen-year-old whose real name is Linnéa, has recently moved to Los Angeles from Sweden, and her dream is to become the most successful porn performer in the city, maybe in the world. If she has any other aspirations, Pleasure is not all that interested in exploring them, making it appear as if she had been born the moment her size 6 stilettos first touched American soil outside the airport. Thyberg means for her pretty blonde lead, whose soft face makes her resemble a competitor-brand Chloë Grace Moretz, to represent an archetype, an ambitious girl chewed up by an industry that runs on female flesh. In the hiking scene, she grumbles and sounds like a whining child; her companion, a Floridian named Joy, turns on her heel to gee her up. “I’m just not interested in seeing that sign,” pouts Bella, “I know what it looks like.” “Don’t you want to see anything in L.A. beside a fucking porn set?” Joy shoots back, annoyed. “No,” Bella grunts.

Film still from the movie Pleasure by Ninja Thyberg. Courtesy Neon

Because Pleasure is set in the present day, the porn sets Joy and Bella see — and by proxy, the ones we see — are almost impossible to tell apart: white McMansions, leased out as Airbnb’s or rented on a daily basis, decked out in the manner of a model home. Always, there is an enormous slouching couch, either in a stain-revealing cream, or in functional wipe-clean pleather; always, there are one or two bright canvases of abstract splashes that might well have been bought in haste at an IKEA. Often, there is an arrangement of cut flowers in a glass vase, looking worryingly like the kind of floral arrangement viewers might remember from the home of an elderly relative or, perhaps, a hospital. (If the sets were minimalist in a slightly chicer sense, we might have banked on an appearance by the famous LC4 chaise lounge, but the kind Bella performs on in the movie are more Walmart-cum-Wayfair than Le Corbusier.) All of Pleasure’s simulated porn environments look, in other words, convincingly like many sets that currently appear on the front-page of PornHub, reflecting a move in current porn towards speedy and high-volume production. These sets now look as empty and as transient as a hotel room one might stay in for a conference.

Film still from the movie Pleasure by Ninja Thyberg. Courtesy Neon

Perhaps contemporary porn sets’ nearness to the anonymous rooms of conference hotels is easily explicable — porn is, after all, a business. Although Thyberg portrays Bella’s experiences in the industry as a lurid arc and crash of brutality and disgust, Pleasure is at its heart a morality tale about sexism and mistreatment in the workplace. The anonymity of the houses Bella works in, each one separated by long stretches of equally-anonymous L.A. freeway, are an interesting mirror for our heroine: however many times she insists that she isn’t “like the other girls,” her success is predicated on her ability to do all the things the other girls do, and look conventionally sexy as she does them. Any signs of personal taste she does display eventually begin to seem like the equivalent of those bright IKEA canvases as far as individuality is concerned. (Overlook some of the body parts in play, and porn is not entirely different from Hollywood acting — to succeed, one has to be convincingly emotional, attractive in a way that fits into a very narrow set of parameters, willing to work hard and for long hours, and able to overlook a degree of harassment and, occasionally, trauma. One interesting, crucial difference, aside from the obvious: it is one of the few fields where women get paid more than men.)

Film still from the movie Pleasure by Ninja Thyberg. Courtesy Neon

During scenes where Thyberg shows the action from Bella’s perspective — in particular, in one where she is looking at a middle-aged co-star’s feet on a white couch — I thought about the photographs of Larry Sultan, the Brooklyn-born, San-Fernando-Valley-raised practitioner who shot on porn sets in the early noughties, focusing not on the action but on the surrounding décor. The Valley, the resulting book, is full of beautifully composed and refreshingly un-alienating images of various porn performers, the mood often either contemplative or knowingly coy: a pair of shapely legs in black foam platforms kicking into shot beside an ultra-70s stone fireplace and a towering yukka; the pale curve of an ass offset by overlapping patterned throw rugs; a petite bleach-blonde girl perching on a sweep of pale-pink fabric on the bed, set into sharp relief by floor-length, purple curtains.

Larry Sultan, Sharon Wilde, 2001. © Estate of Larry Sultan. Courtesy Casemore Kirkeby, San Francisco; Yancey Richardson Gallery, New York; Thomas Zander Gallery, Cologne.

Larry Sultan, Den, Santa Clarita, 2002. © Estate of Larry Sultan. Courtesy Casemore Kirkeby, San Francisco; Yancey Richardson Gallery, NY; Thomas Zander Gallery, Cologne.

Larry Sultan, Mulholland Highway, 2000. © Estate of Larry Sultan. Courtesy Casemore Kirkeby, San Francisco; Yancey Richardson Gallery, NY; Thomas Zander Gallery, Cologne.

No two houses in The Valley look the same, even if they share a similar lived-in nouveau-riche aesthetic. Sultan first became interested in photographing porn sets after a 1998 magazine assignment during which, entering a Los Angeles family home that was still full of family photographs and domestic detritus, he was greeted by six naked women in slithering, fleshy heap. “It was as if the family had vanished,” he observed, “and this strange new family had come in.” “In The Valley, I wasn’t interested in pornography as a phenomenon,” he told an interviewer in 2008, “but in how it uses domesticity as a narrative. The sex industry can be such a tired, worn-out subject, but when it’s imported into kitchens and dining rooms of a middle class suburban home, something new opens up.” In other words, what drew Sultan to the sets he documented was a different kind of banality: one that had nothing to do with anonymity or emptiness, but with the fact that, to paraphrase Tolstoy, happy families all express their individuality in their homes in ways that are alike, intending to telegraph good taste or status or domestic bliss. “The home,” he said, “is so much about theatre.” A lived-in home and an adult production, then, are not as unlikely a fit as one might think, since what is more about theatricality — the performance of a heightened version of a particular, universal facet of human experience — than porn? When we talk about “interiors porn,” what we mean are gratifying images that offer us a glimpse into somebody else’s home life, even if that life is staged; as in a sexual fantasy, we project ourselves into the image, what is or is not attainable being made irrelevant in the face of desire.

Film still from the movie Pleasure by Ninja Thyberg. Courtesy Neon

Film still from the movie Pleasure by Ninja Thyberg. Courtesy Neon

Near the end of Pleasure, Bella finally has a shoot in a house that more closely resembles something from The Valley, looking out-of-time and baroque in a way that, even if it is in bad taste, certainly reveals taste of some kind on the part of its inhabitants. Walking in, she passes an extraordinary living room decked out in pseudo-antique furniture, upholstered in pale velveteen, and a newel pole at the foot of a spiral staircase that is topped with a large sculpture of a cherub; her black heels rap out a rhythm on a milk-white marble floor, keeping time. In the bedroom where the film is to be made, there is a canopy bed in filigreed gold and deep royal purple, everything looking as if it had been purchased by Louis XIV. It is Bella’s first scene with another, far more famous girl, a stuck-up professional rival; the director wants the mood to be romantic, meaning that he’s presumably chosen the location to imply a certain classiness, a nod to paperback romance novels or to raunchy period movies in which this home might belong to a tycoon, or a prince. Because Bella has by this point been left traumatized by a rough shoot that seemed to tip over into something like rape, and because the other actress is her professional nemesis, she takes the opportunity to sour the scene, turning things dark — an intrusion of the painful and the real into a frothy theatrical simulation. If they are playing house, Bella has cast herself as the frightening, domineering daddy. The contrast between the action and the setting suggests what Sultan described as “domestic disorder,” a phenomenon in which “what is cozy and homey is made uncanny and unsettled.” Once the film was over, I felt moved to fire up PornHub and assess the accuracy of Pleasure’s set design, clicking through thumbnail after thumbnail of sterile white décor until finally, one clip stopped me short — a video by an amateur performer, seemingly made in her studio flat, in which the ubiquitous sectional couch had been appended with a single slogan cushion, turned so obviously to face the camera that I felt sure she had put it there deliberately to make a joke: THERE IS NO PLACE, it read, LIKE HOME.