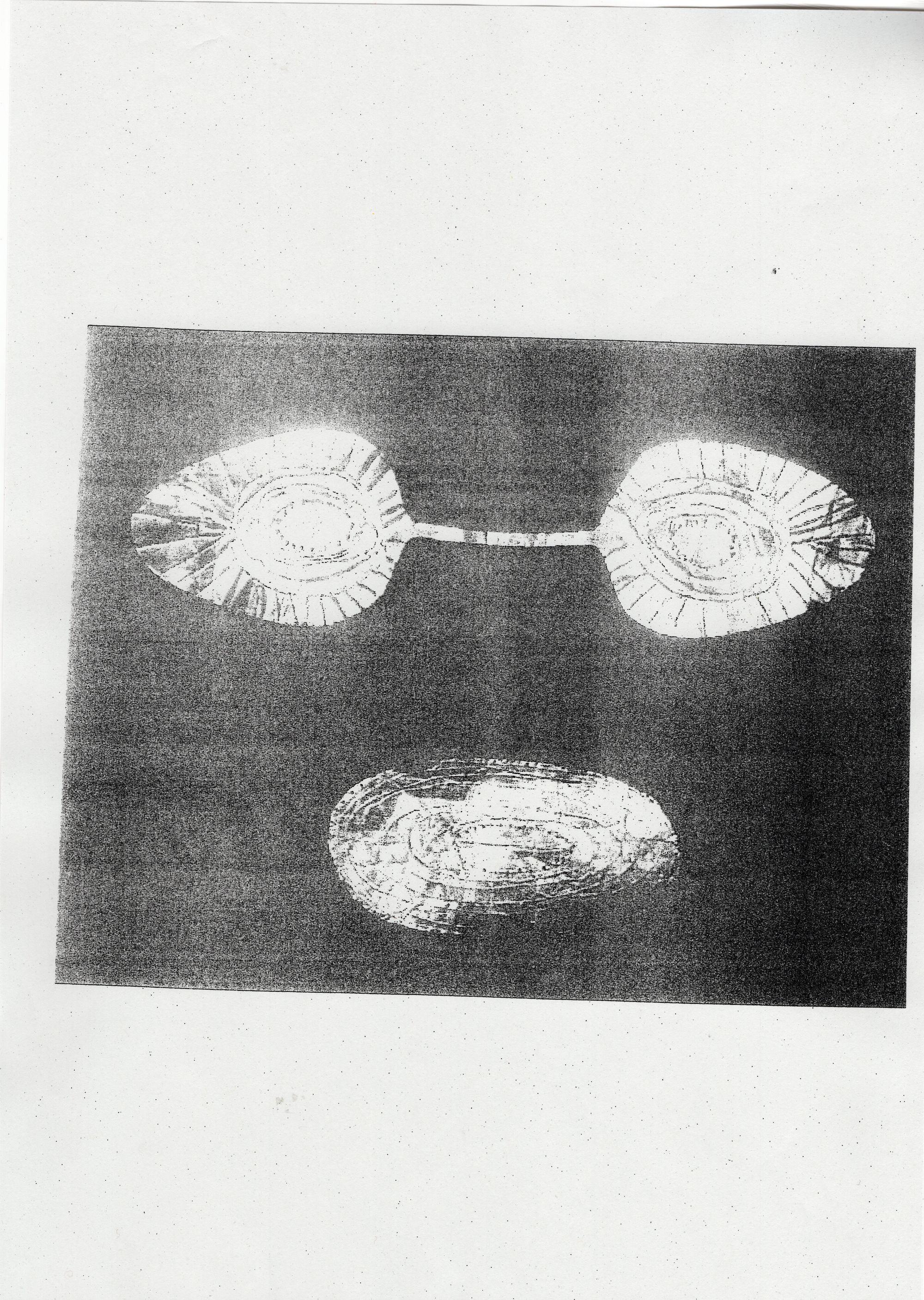

An outline of a Scythian gold earring, a Xerox of one of the many artifacts looted from Ukrainian museums that the artists involved with The Phantom Museum seek to reproduce based on their memories or imaginations.

An outline of a Scythian gold earring, a Xerox of one of the many artifacts looted from Ukrainian museums that the artists involved with The Phantom Museum seek to reproduce based on their memories or imaginations.

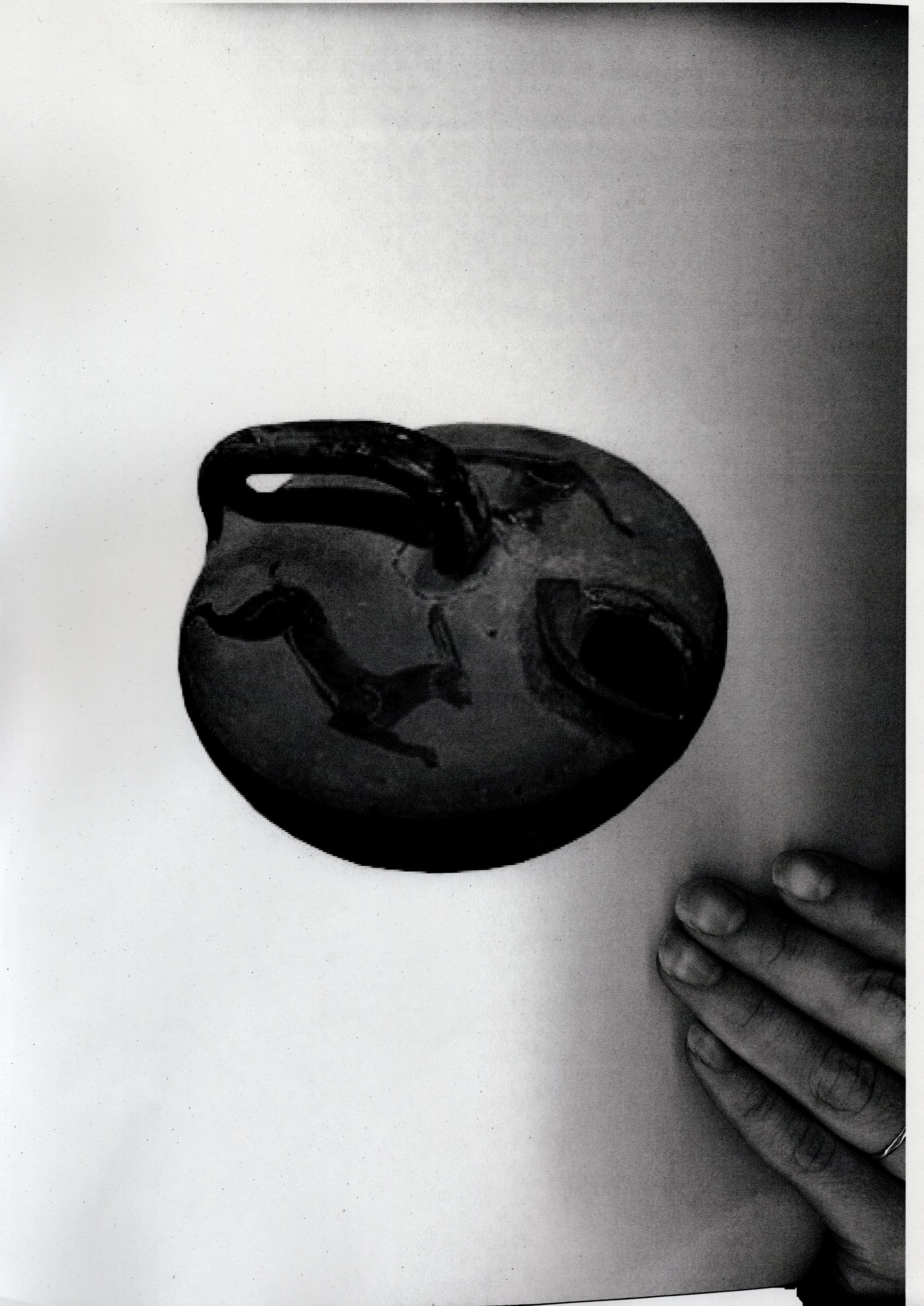

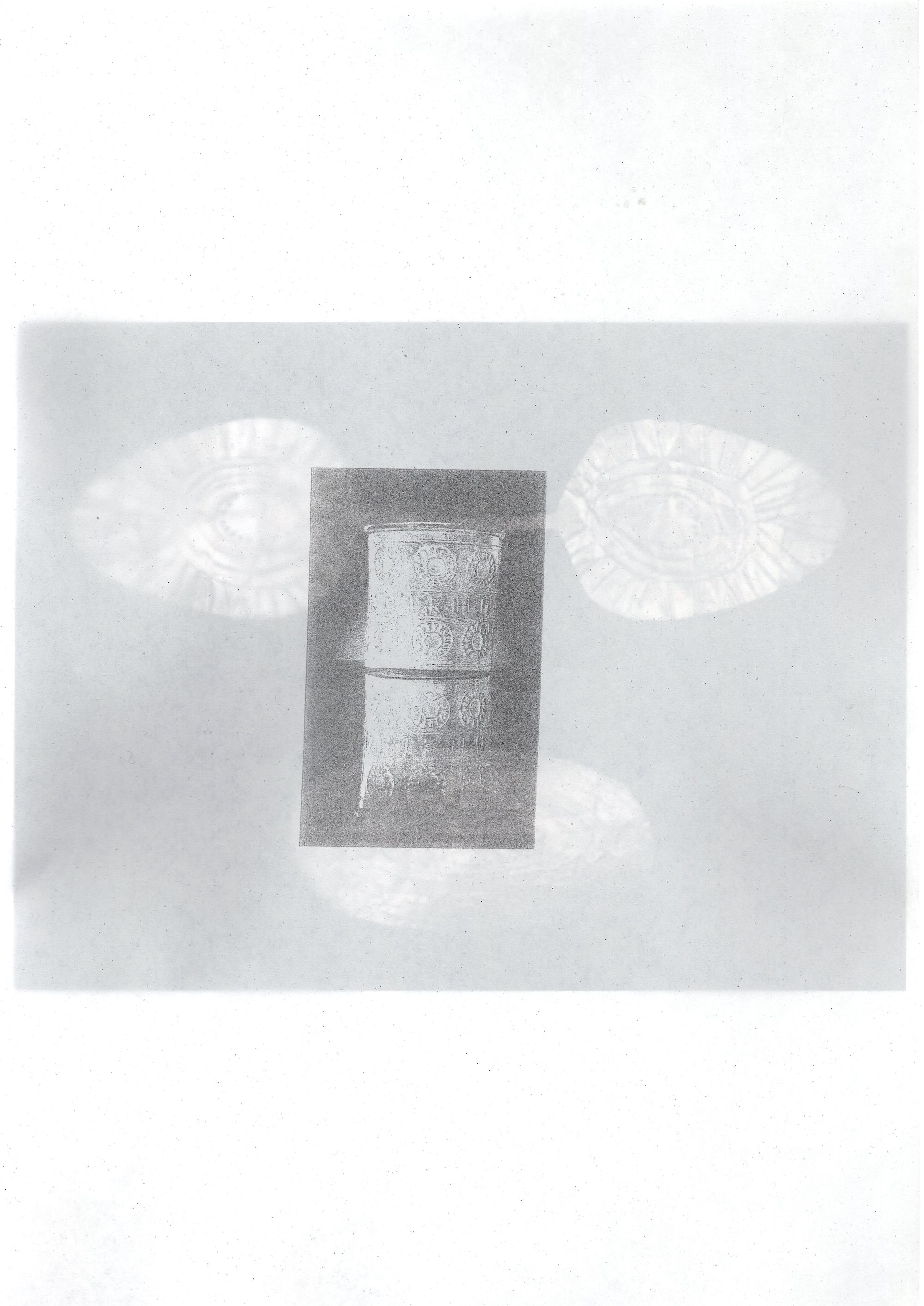

Figurative vessel in the form of a leg dressed in a cothurn.

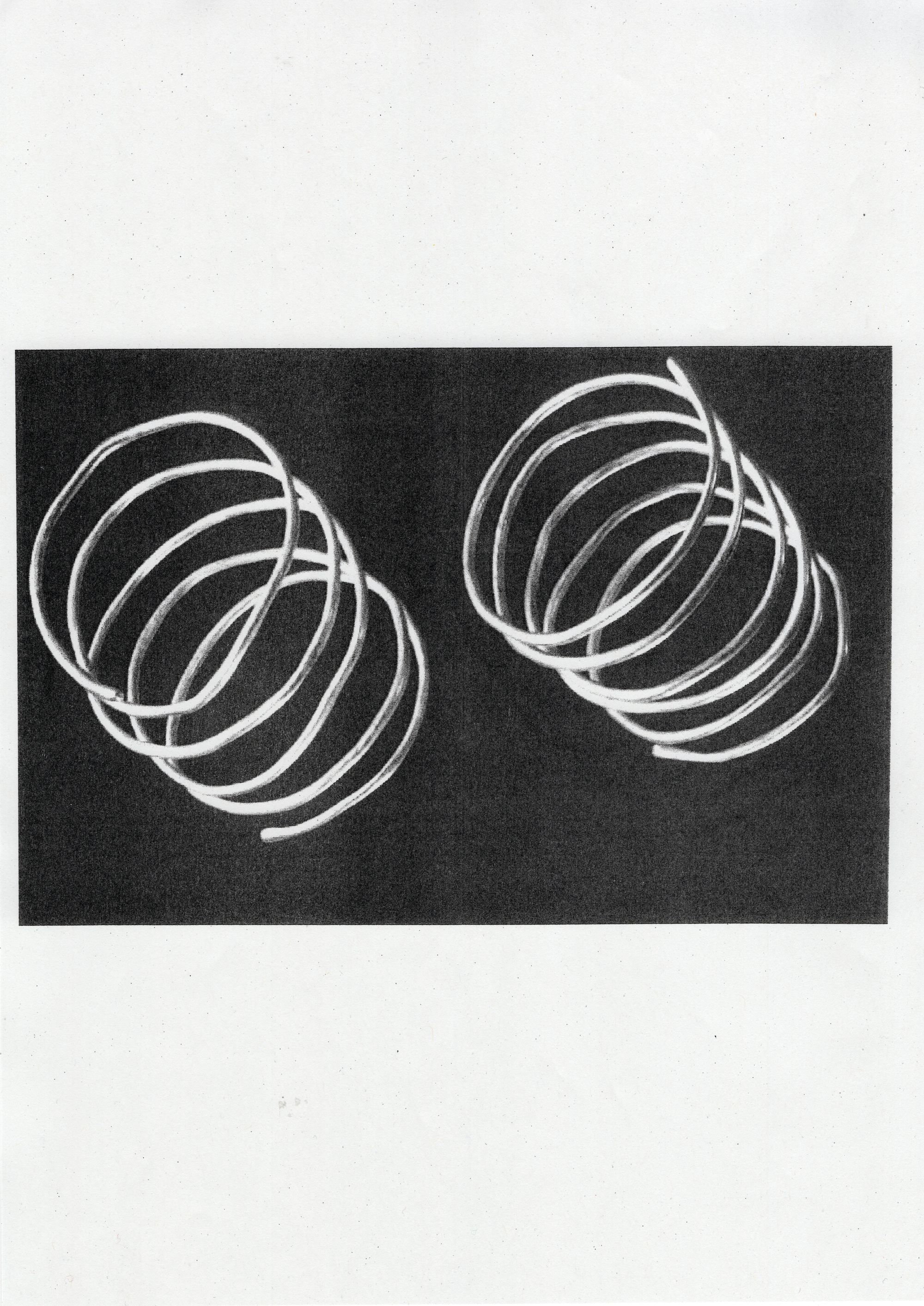

Gold funeral eyelets and mouthpieces appropriated by Russian archeologists during illegal excavations.

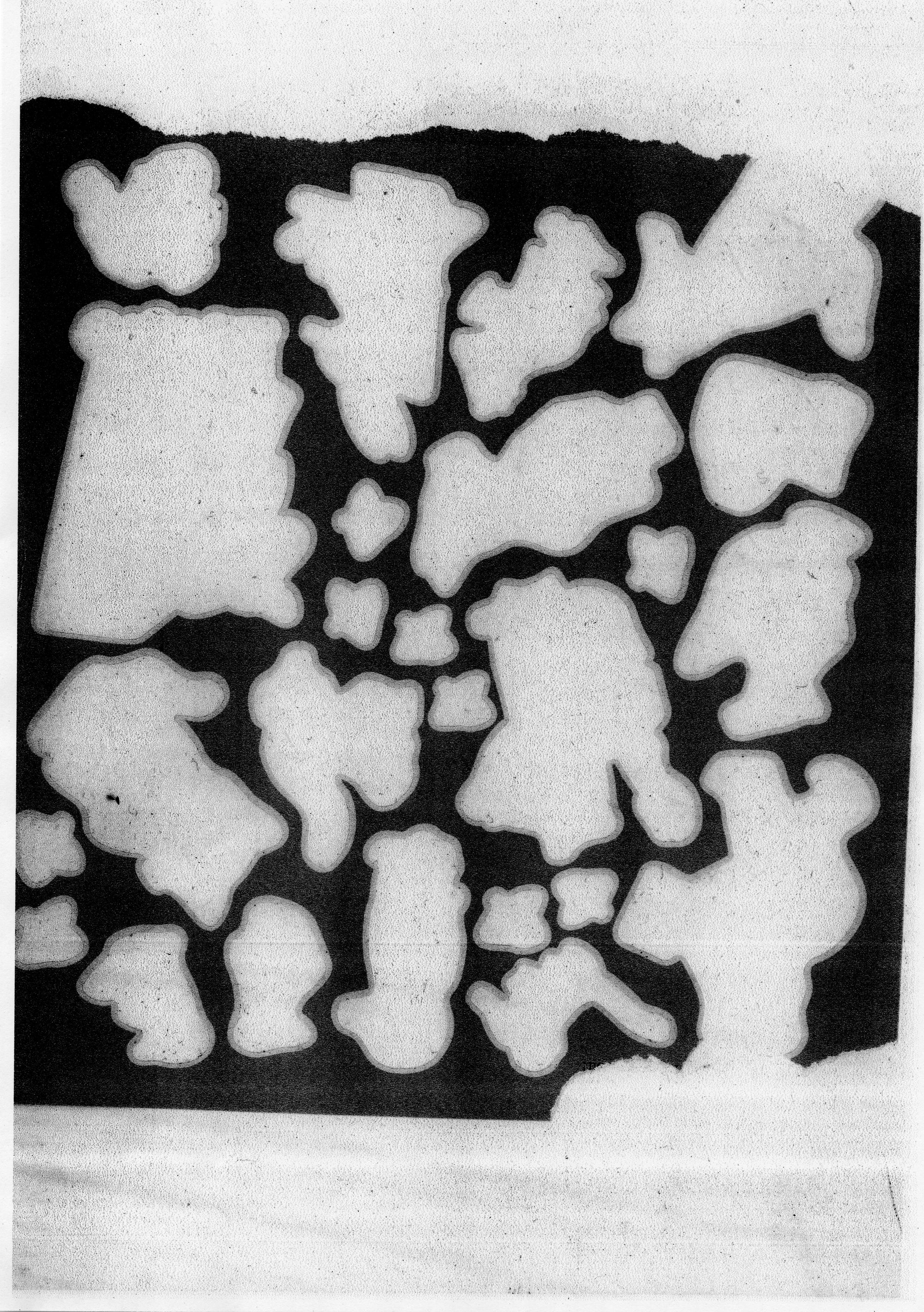

A used sticker pack from The Phantom Museum.

In medical terminology, the word phantom refers to something that exists only in a person’s mind. Phantom pain, for example, is when one feels an ache in a limb that they no longer have. This condition can be treated using a mirror box: a person who has lost one hand inserts the remaining hand into a box with two holes, bisected by a mirror, which creates the illusion of two hands. When the brain is tricked into believing both limbs are intact, the pain diminishes.

By exhibiting “conceptual” copies of artifacts looted from Ukrainian museums, The Phantom Museum brings this same illusory logic to the opening of the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw. The initial stages of The Phantom Museum were guided by the work of artist Olga Gaidash, who has been replicating museum artifacts since her 2021 project at the Khanenko Museum in Kyiv. Gaidash and I had wanted to work together since then, but with the war, relocation, and dispossession, our focus scattered. That is, until we began to conceive of a “museum” of conceptual copies of stolen objects — those existing in limbo somewhere, burdened by a heavy context and history.

As part of a methodical campaign to erase Ukrainian identity, many Ukrainian artifacts have been stolen and installed in Russian museums, where they are presented as “evidence” of fabricated histories. Russia has been systematically destroying and appropriating Ukrainian culture for centuries, but the scale of this erasure expanded dramatically after 2022. In the decade prior to the current, full-scale war, this looting was particularly prevalent in annexed Crimea and the occupied territories of Donetsk and Luhansk. The Phantom Museum recommissions historical artifacts without access to the originals, instead asking artists to reconstruct these objects based on their memories or imaginations, building shared ideas through conversations among The Phantom Museum team members. The replicas were crafted without the artists ever having seen the reference objects, in real life or in photographs. Reference images and research materials were drawn from defunct websites or archaeological details printed in museum catalogues that have been re-Xeroxed many times over.

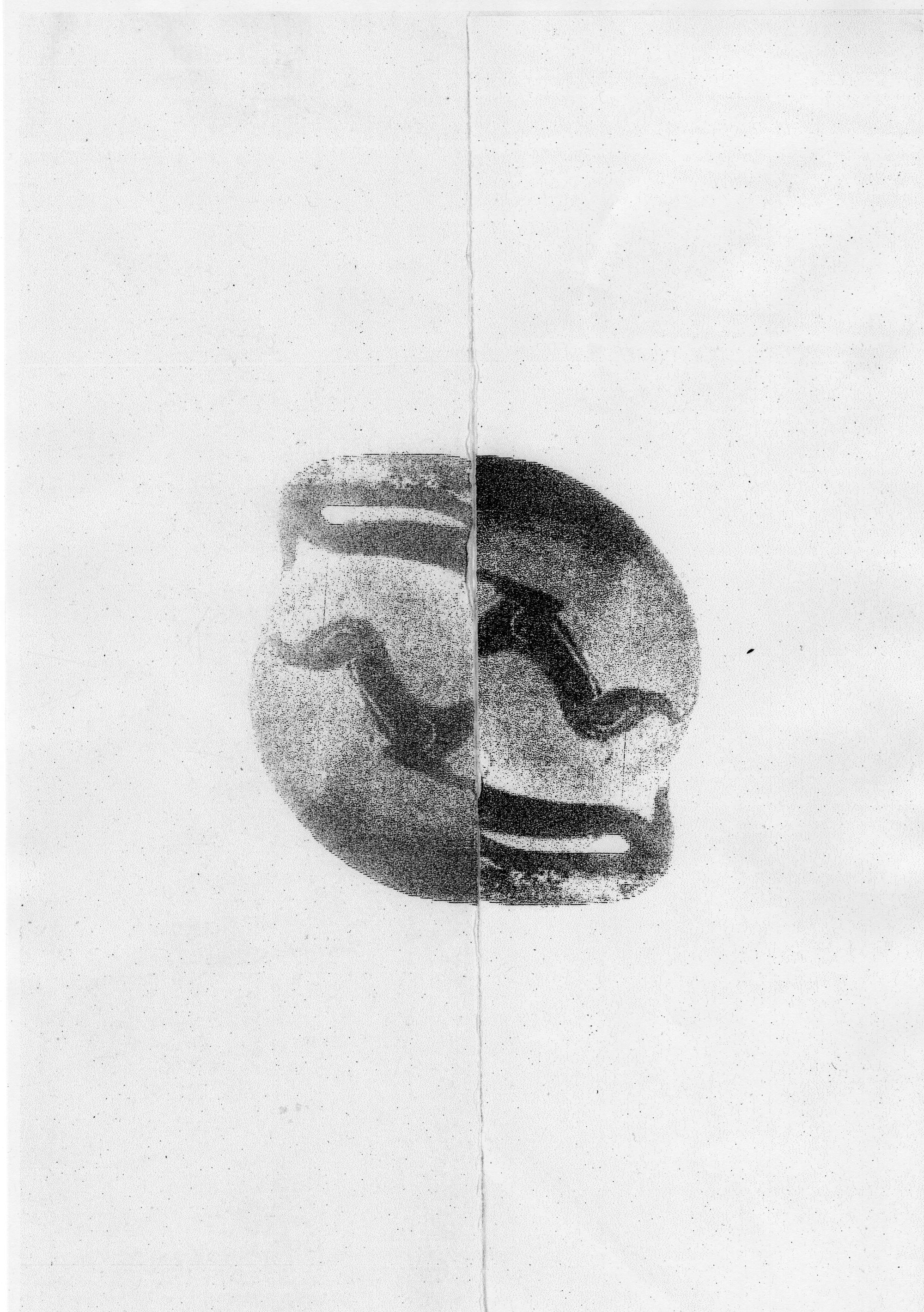

Black-Figure Ascus of the Ionian Culture.

Black-Figure Ascus of the Ionian Culture.

Black-Figure Ascus of the Ionian Culture.

Ivan Bazak handcrafted several replicas for The Phantom Museum: two ancient Greek vessels and an earring decorated with a massive lion’s head — all in wood. The latter was based on a piece of Sarmatian gold, featuring a lion’s mane comprising three rows of spiral cones. While working, Ivan said he was reminded of carving out zoomorphic motifs on the wooden balusters of his house in Western Ukraine, which coincidentally, had also been stolen — torn from the façade after the house was left uninhabited for a long time.

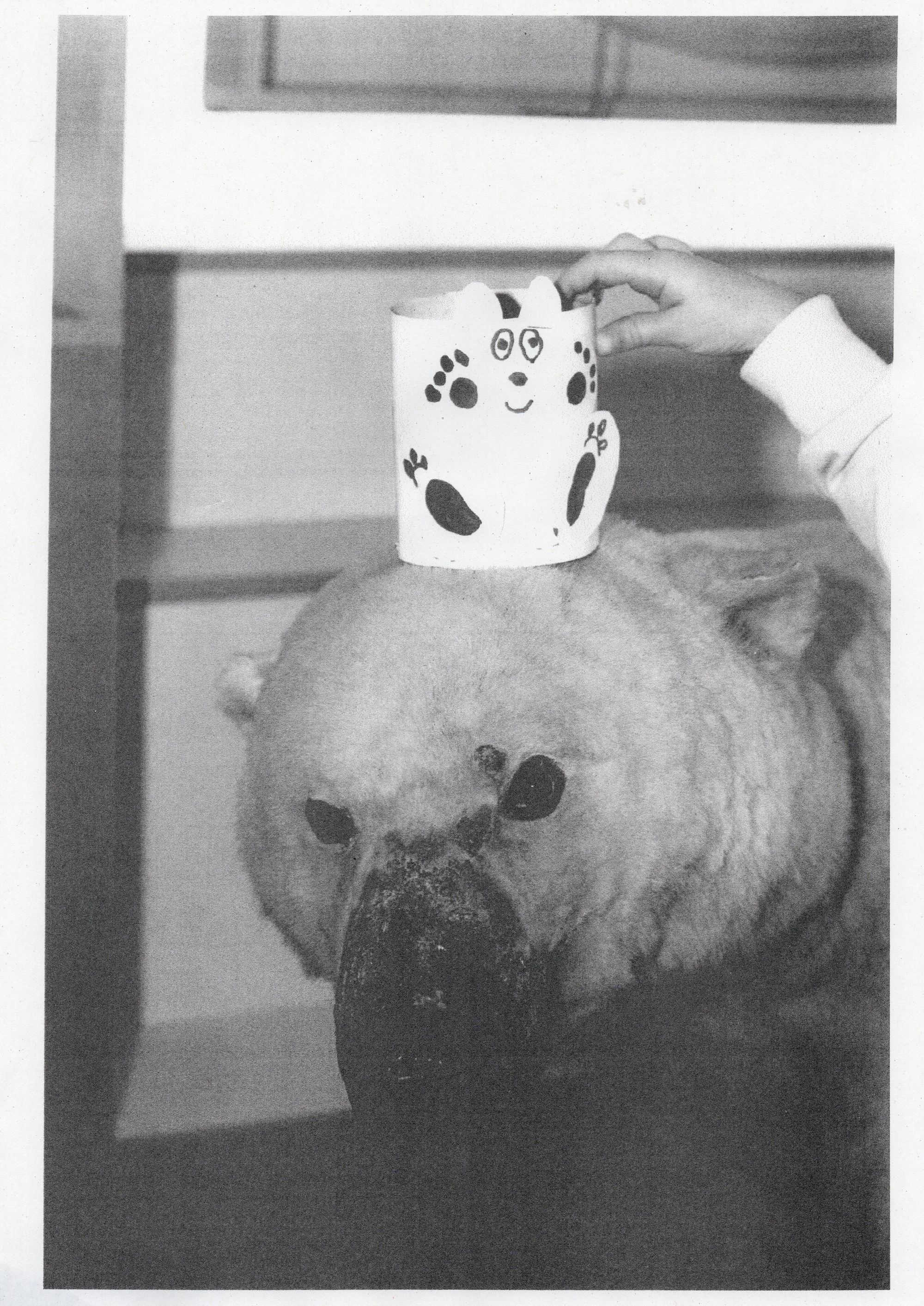

A vessel in the shape of a foot dressed in a cothurn is represented by two objects, both inspired by fragmentary recollections of this artifact from the Kherson Local History Museum’s collection. The first, crafted by Violett e a, integrates the foot-shaped vessel into a platform. The second, a wooden object meticulously carved by Bazak, offers a more tactile interpretation of the referent. Both allude to ancient Greek theatre and the actors’ distinctive cothurnus shoes, designed to add height, enhancing their visibility among vast audiences. The vessels offer distorted reflections of each other, as if seen through a funhouse mirror.

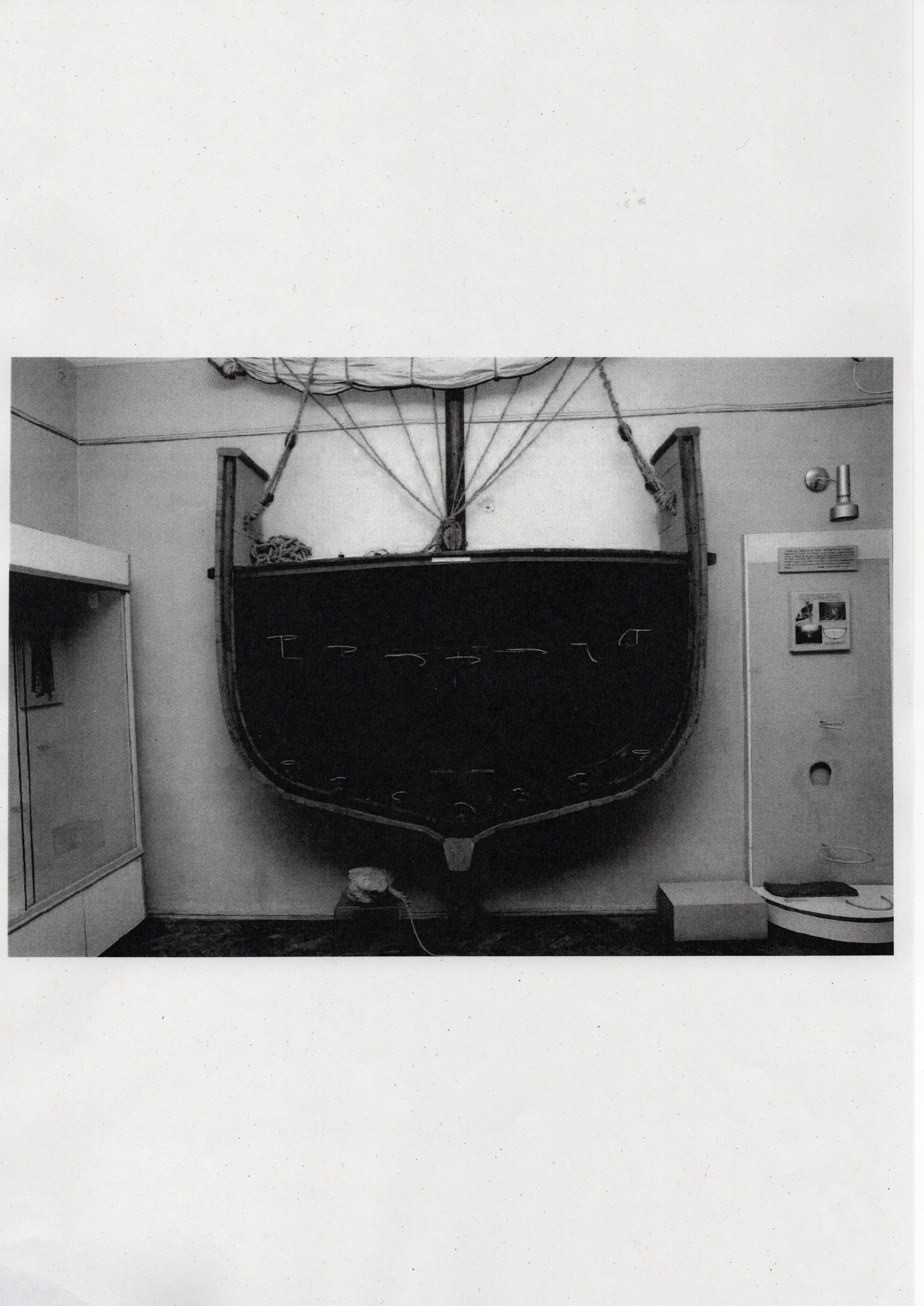

The artifacts sit atop of a double-layered horizontal surface, which allows objects to be partially submerged in its lower layer. The platform, levelled to the ground to evoke an architectural ruin, was made by Centrala, the team of Warsaw-based architects, in collaboration with Violett e a, using found materials in the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw’s storage, including scraps from previous shows, like Maria Prymachenko’s retrospective. Some materials are a bright yellow, some are MDF slabs painted a muted red. The architects worked from the images of looted museum vitrines that abound in recent media coverage of the war in Ukraine.

Sarmatian gold bracelets from Kherson.

Glass cup with Greek inscription “I Will Win,” looted during the illegal excavations from Crimea.

Display case in the Kherson Local Lore Museum after the Russian occupation in October 2022. Xerox sourced from photography by Olena Kravchenko for Hmarochos.

A copy of a polar bear made by a visitor at the Kherson Local Lore Museum. Photo retrieved from the Museum of Nature at the Kherson Regional Local History Museum.

Also on display in The Phantom Museum is a replica of a limestone stele dating between the first and second century AD, made by Oleksandr Koshchei — a prop maker working in Kyiv. The stele depicts Diomedes, hero of the Trojan War, as was traditional in Tauric Chersonese, an ancient Greek settlement and UNESCO World Heritage site that spans much of what is now occupied Sevastopol. In 2023, under the guise of evacuating Sevastopol museums for safety, occupiers removed Byzantine artifacts from Chersonese and have since begun to destroy the site through the illegal construction of propaganda installations. In order to justify their claims to these lands, Russian authorities conduct pseudohistorical tours of them. Occupying forces are currently constructing more than 70 new buildings there, including museums, workshops, educational centers, and an amphitheater. One of these museums, the Museum of Crimea, is nearing completion and is sure to be a powerful source of propaganda. Another new structure, a theater with a 60-ton stage, has damaged the historical site that lies beneath it: the only Roman citadel preserved in the Northern Black Sea region. Russian-state-media images of the construction site show bright buildings, manicured lawns, and bridges resembling stage sets juxtaposed against the backdrop of these ancient ruins.

The notion of theater plays a crucial role in The Phantom Museum. Scenographers and prop makers are usually tasked with creating an illusion of reality on stage. And yet, up close, this reality begins to fall apart, revealing its artificiality. The Phantom Museum seeks to recreate this feeling of reality diminished by proximity, and to question the role of artifacts in the construction of historical truth. A mirror box creates a functional illusion, and the pain is lessened.

Dispossession isn’t just about the tangible loss of land or material possessions, it’s also about the immaterial, often invisible losses that erode one’s sense of self and community over time. The Phantom Museum seeks to confront these losses by exploring how they shape our present and future. Amid Russia’s attempt to destroy Ukrainian culture, it is essential that we employ our transnational networks, imaginations, and fragmented memories and stories to resist and reaffirm our existence.