Oslo Neighborhood Lab. Photo by Are Carlsen.

Oslo in the Making at the Olso Architecture Biennale. Photo by Are Carlsen.

In late September, I landed in Norway’s capital for the Oslo Architecture Triennale. A cross-pollination of ideas is how head curator Christian Pagh envisioned the centerpiece of this year’s happening, a multi-exhibition culture house dubbed the “Oslo Neighborhood Lab.” Taking the neighborhood as its guiding theme, the Triennale’s eighth edition focused on creating sustainable and inclusive living by rethinking and remodeling urban planning at the human-scale. The centering of the neighborhood made sense in the wake of Covid lockdowns, which very recently restricted many of us for the first time to our immediate vicinity, putting new emphasis on the importance of ideas like the 15-minute city (ensuring access to all necessities within a short walk or bike ride). And as private equity continues to transform real estate around the globe, projects like Noisy Neighbors, a Malmö-specific case study on how we can prevent neighborhoods from being turned into developers’ assets, felt particularly urgent. Some contributions — for example, the call to action for a co-op located in a parking space or a study on the poetics of daylight — felt fated to remain in the world of ideas. Others were more pragmatic, like JAJA Architects’ proposal for decreasing car traffic in Copenhagen or BIG’s design solutions for decentralized geothermal energy plants. Still, moving through the exhibitions I did feel a creeping concern about the chasm between idea and action, between well-meaning provocations and what could really do the most good for the most people. I wondered if my anxiety was cultural. After all, here I was in Scandinavia where utopian fantasies of urban planning came true.

Oslo Neighborhood Lab. Photo by Are Carlsen.

Freie Mitte by StudioVlayStreeruwitz. Photo by Are Carlsen.

It was my first time in Oslo, but I was quick to catch onto how the city is changing. The majority of the Triennale’s activities were headquartered at the Old Munch, a Modernist building from 1963, about a 25-minute walk from the waterfront where most of the press and exhibitors were staying. In a way, Old Munch has been left behind as the city’s energies have focused on developing the waterfront with high-profile cultural institutions, including the New Munch (the reason for the Old Munch’s new moniker), a Juan Herreros-designed 13-story “eyesore” (that’s how the locals I spoke to described it). Rebranding as MUNCH, the museum’s new location opened in 2020 right beside Oslo’s famous opera house, for which Norwegian firm Snøhetta won a World Architecture Award. This glacier-inspired white marble landmark was completed in 2007, marking the first chapter of a massive urban redevelopment project known as “Fjord City,” which is still underway today. Where the waterfront was once home to shipping containers and industrial fishing boats, the city has now devised a cultural district. The latest phase has seen the completion of the nearby light-filled Deichman Library (Atelier Oslo + Lund Hagem, 2020), the gargantuan gray slate National Museum (Klaus Schuwerk, 2022) on the Aker Brygge boardwalk, and of course the new Munch Museum.

The Munch Museum by architects Gunnar Fougner and Einar Myklebust, photographed in 1963, shortly after completion. Photo: Teigen Fotoatelier/Norsk Teknisk Museum/DEXTRA.

Construction site of the current Munch Museum at Bjørvika, December 2020.

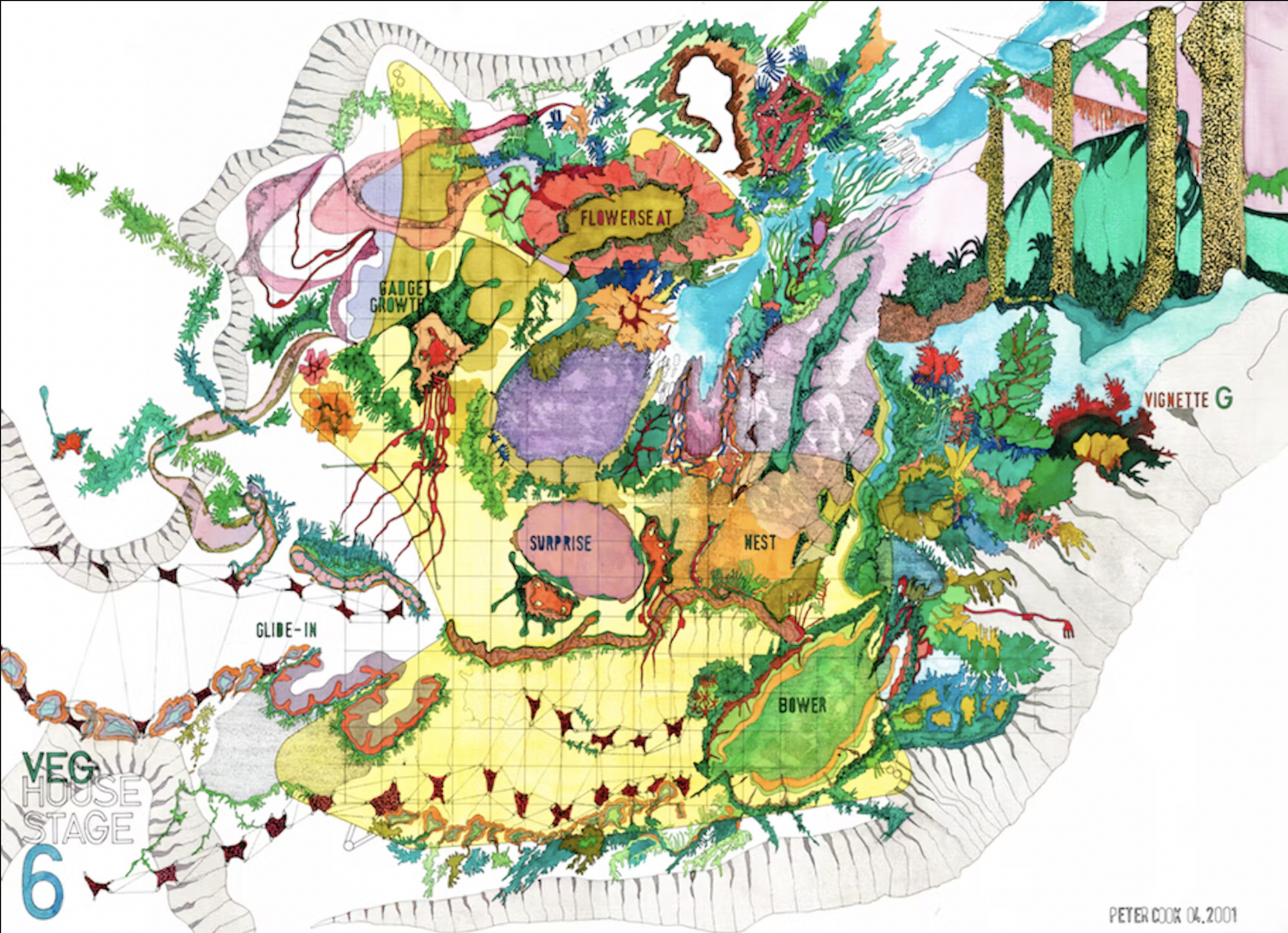

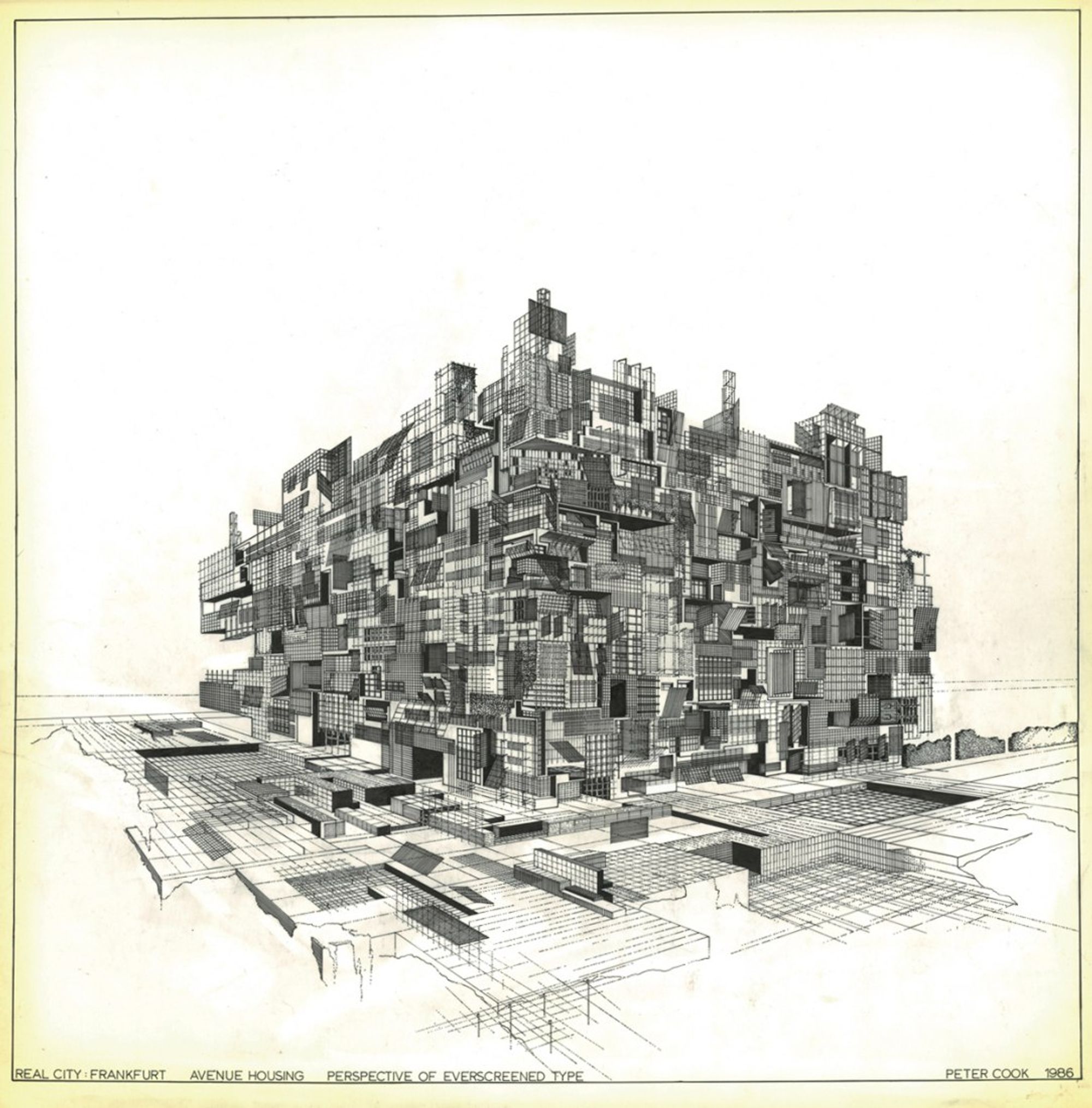

This agenda to congregate all the cultural institutions along the waterfront has left the fate of the Old Munch unclear. This uncertainty was a subject that the Triennale addressed by including proposals from architecture students for how the concrete building designed by Einar Myklebust and Gunnar Fougner could be repurposed — and while it’s not near the water, Old Munch is in a great location, adjacent to a sprawling park with a botanical garden and blocks from the city’s best vintage shopping and hip cafés. The suggestions of how the 1963 building could be repurposed spanned a greenhouse for growing food and a center for music festivals. Also at Old Munch, there was an exhibition by Archigram-founder Peter Cook who presented the beautiful sci-fi speculative cityscapes he’s been drawing since the 1960s. The Triennale’s program there also included a presentation of proposals for the next phase of Oslo’s multi-decade waterfront redevelopment project: Grønlikaia. On view were models made by the winners of an open-call competition held by the developer, Hav Eiendom, which asked for input on how the former industrial harbor can meet the community’s needs and desires for sustainability as it transforms into 1,500 new homes; over 3,000 workplaces, shops, and cafes; and a kilometer of waterfront promenade and public space. As a New Yorker, I’m skeptical of commercial developers paying lip service to sustainability, but here in Oslo, I felt more optimistic. The mixed development near the Opera House, with both housing and restaurants, seemed idyllic with plenty of infrastructure to make the waterfront available for the public to swim, kayak, and sauna (everything free or affordable).

Peter Cook’s Idea for Cities.

Peter Cook, Real City: Perspective of Everscreened Type, 1986. Courtesy Peter Cook.

Global architecture and design biennales and triennials often exemplify how architecture has changed over the years. Where at the turn of the 20th century, international expos acted like trade shows, showcasing the nuts and bolts of construction and engineering, as well as spotlighting innovative new materials, over the past 30 years the discipline has headed toward something more akin to cultural studies and sociopolitical anthropology. The criticism is that the ideas, as well-meaning as they are, become limited to an academic bubble. As I walked each day through the immigrant-rich neighborhood of Grønland on the way to the Old Munch, I did wonder if the ideas in the lab would end up benefiting the working-class people who lived there, or just stay ideas in the form of wall texts and diagrams, mostly for students and journalists. During one of the opening seminar speeches, Katja Lindroos, a co-founder of both the Helsinki-based firm Urban Practice and the Nordic CityMaking Week, had some advice that stuck with me: We don’t need to find the best idea, Lindroos argued; we need to find a vision that enables the most people possible to contribute.

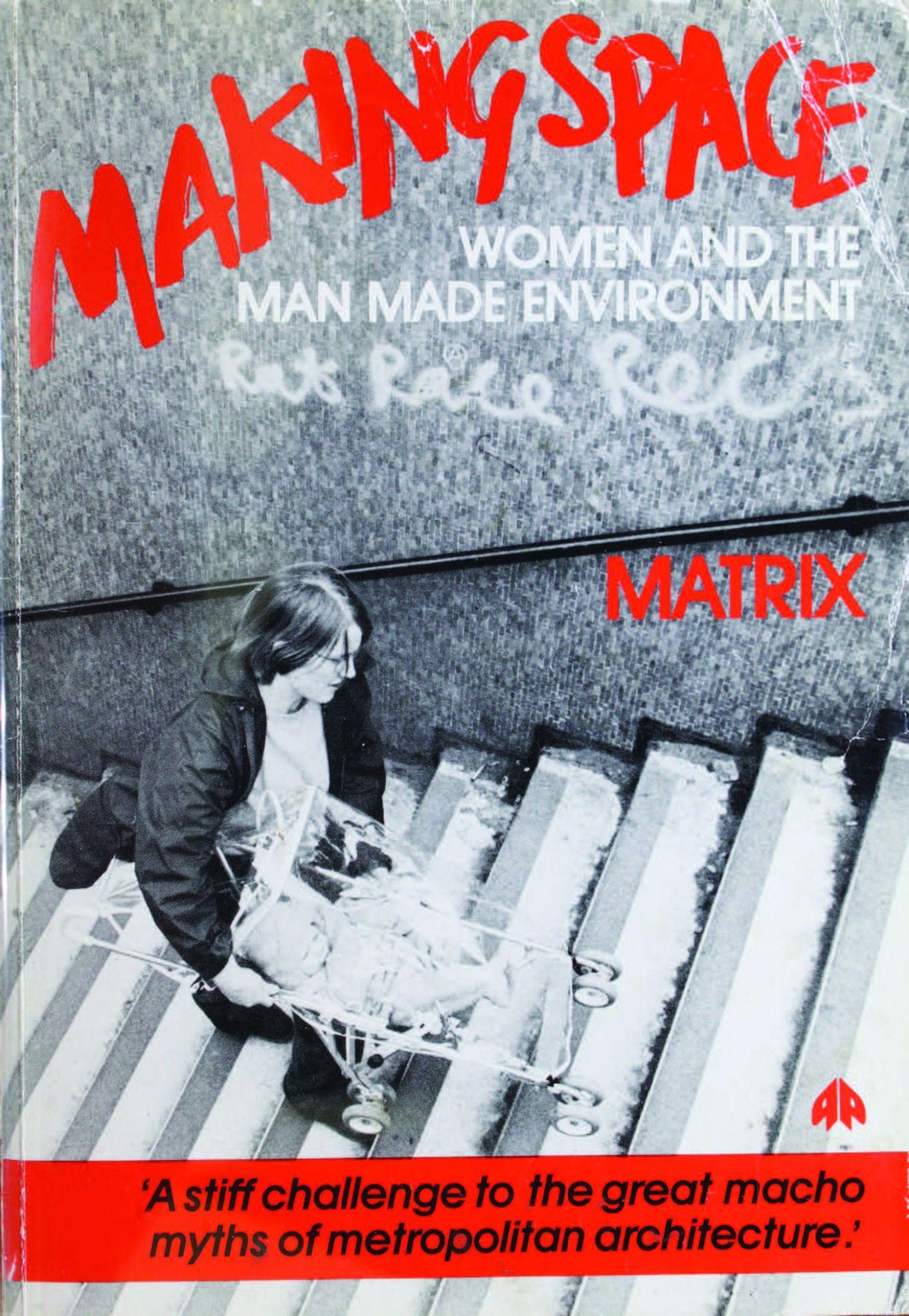

While Old Munch was the Triennale’s beating heart, it was not the only venue to showcase its programming. My favorite exhibition, Coming Into Community, was presented at the National Museum for Architecture, a 19th-century building with a Sverre Fehn addition, a short walk to the waterfront, in between MUNCH and the Opera House and the brand-new National Museum. There the recent history-focused Coming Into Community underscored the hands-on nature of specific architectural interventions from the second half of the 20th century. Matrix, a London-based feminist architecture practice established in 1980, was highlighted — their book Making Space was just republished by Verso. And one of Matrix’s founders, Jos Boys, gave a talk, explaining how the co-operative aligned women architects, lesbian squatters, and tradespeople. (Boy also spoke about her current project The DisOrdinary Project, a platform for disabled artists to lead accessible design discourse).

Coming Into Community exhibition view. Photo courtesy of National Museum/Børre Høstland.

London-based feminist architecture practice Matrix.

Matrix’s Making Space.

The exhibition Coming Into Community also told the story of Selegrand Hesthaugen, a 1960s housing project located just outside the Norwegian city Bergen, one of the first housing projects where the nuclear family was no longer the main focus. In Selegrand Hesthaugen, one-third of the homes were to be reserved for housing-vulnerable groups — immigrants, people with disabilities, single parents. Participation in the building process ensured costs were kept low. People were empowered with the skills to make their own housing.

Another subject of Coming Into Community was the Svartlamon neighborhood in Trondheim, another Norwegian city, demonstrating how a successful anarchist community was birthed through years of political struggle. In the late 19th century, this gathering of homes was first established as a working class neighborhood on the city’s outskirts, whose residents in the 1940s successfully fought policies to rezone it for industrial use, saving the community. Later when it was on the downswing, counterculture types started moving in the 80s — punk and grunge squatters in a neighborhood that was once again scheduled for redevelopment. In 1996, as a tactic to save homes from demolition, local artists painted murals on the exteriors, and then gifted these artworks to the city. Their tactics worked. Today, Svartlamon is defined as an autonomous eco-community with an owner-operator housing model.

These histories of Matrix, Selegrand Hesthaugen, and Svartlamon all underscore the value of participation and co-determination. They are proof we’ve known all the important stuff about the intersection between marginalization and housing for decades, we just don’t have the solutions embedded in our culture. It all left me wondering what a more hands-on model for biennales and triennales could look like (the mess of Documenta maybe both a paradigm and a warning). What if the next international architecture event was organized as an evening program of lectures and performances after communally-prepared meals and Habitat for Humanity-type cooperative building? Do we need more idea festivals? Or do we already know what’s good for us, and what we really need are more systems to organize our energies?