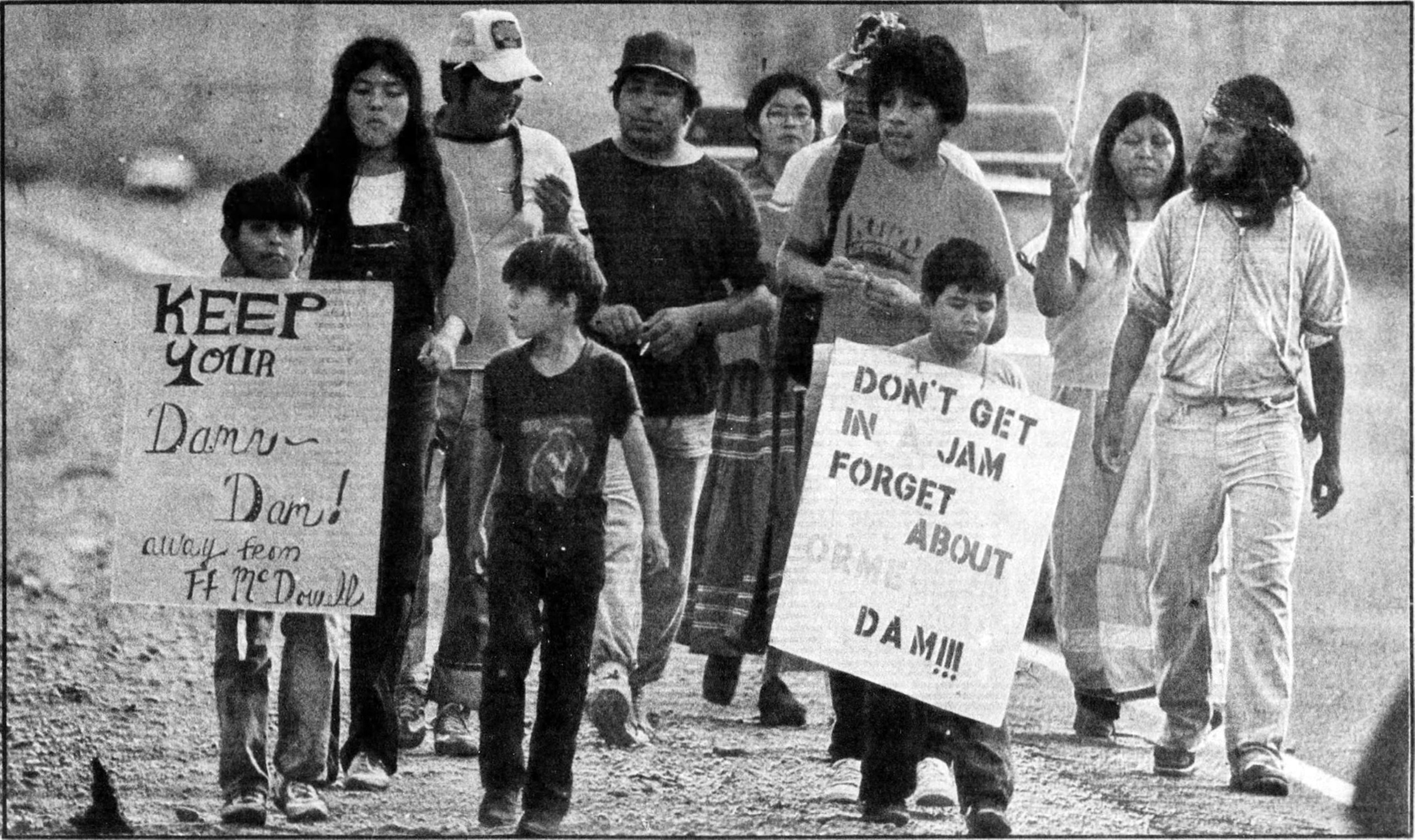

“A necessarily selective survey,” as Chan acknowledges, MoMA’s representation of “environmental architecture” is compromised by “the irretrievable loss of ecological knowledge developed for millennia before European settlers colonized this land.” Transfixed by the Anglo-American milieu of the 1960s and 70s (a spacetime saturated by recent architectural research), the exhibition diligently hints at, when possible, leakages in its inevitable insulation within a settler colonial framework. Yet, when other subjects do appear in the exhibition, they are hung as pictures of resistance insofar as they perform the work of discursive correction and legitimacy. Framed as a salient defense of indigenous sovereignty through documentary photographs and news clippings, for instance, Fort McDowell Yavapai Nation’s decade-long legal battle against a land-effacing dam, which established precedent for resistance through the legislative system, might indicate openings in a remedial framework of environmental institutionalism; however, it also suggests a dismal outlook where any refuge of a world worth living from capitalist development’s ruination machine is left up to the arbitration by its own green governances, bureaucracies, and deals.

What is left unclear in recycling the historical emergence of particular environmental politics — which may have already been bankrupt — is how these sporadic, if individualistic, episodes connected to the larger political ecologies at the time. In his recent book Scorched Earth, Jonathan Crary identifies the tragic negligence, if not dismissal, of many prescient ecological accounts in anti-systemic struggles erupting in advanced capitalist countries in the 1960s and 70s, when environmentalism failed to gain political momentum with broader liberation, anti-war, and student movements. One way to engage with Emerging Ecologies is to identify a sprawling yet patchy field of past praxis from which we may salvage architecture and its history’s political purchase in the environment, only to take it apart to forge new, enduring webs of solidarity with struggles of the many systemic violences of our time, spectacular or slow.