Miguel Milà photographed by Nacho Alegre. Photo courtesy of Madrid Design Festival.

Miguel Milà photographed by Nacho Alegre. Photo courtesy of Madrid Design Festival.

Casa de Miguel Capilla designed by Miguel Milà. Photo courtesy of Madrid Design Festival.

For 93-year-old Miguel Milà, “the day I dropped out of architecture school was the happiest of my life. I finally felt free.” The star turn at the seventh Madrid Design Festival, Barcelona-born Milà spent six years at ETSAB, his home town’s architecture faculty, but struggled with the math-oriented teaching of the times. Nonetheless, the skills he learned during his studies, as well as the friends, colleagues, and professors he met along the way — among them the celebrated Catalan architect José Antonio Coderch — allowed him to find his true vocation: as an interior and industrial designer. With the help of the husband-and wife curators Claudia Oliva and Gonzalo Milà (Miguel’s son, also a designer), the prolific nonagenarian, who is still working today, has just inaugurated his biggest retrospective yet at Madrid’s Fernán Gómez cultural center.

A hero in his hometown, where people remember his streamlined restyling of the city’s subway cars and still use his street benches, Milà is appreciated by aficionados in Madrid but relatively unknown outside his native land. If the family name seems familiar, it’s because a cousin of his father’s, Pedro Milà, commissioned Antoni Gaudí to build the celebrated Pedrera apartment building in Barcelona (aka the Casa Milà), which Miguel considers the architect’s best work because the client did everything he could to dampen Gaudí’s usual exuberance. “Miguel’s father was an upper-class dandy [Alfonso XIII made him Count of Montseny] who liked high-quality clothes and furniture,” remembers Gonzalo Milà. “His mother, on the other hand, was rather austerely Catholic and hated waste. A family member once overheard my grandmother say, ‘My greatest dream is to go into a big cathedral and clean everything.’”

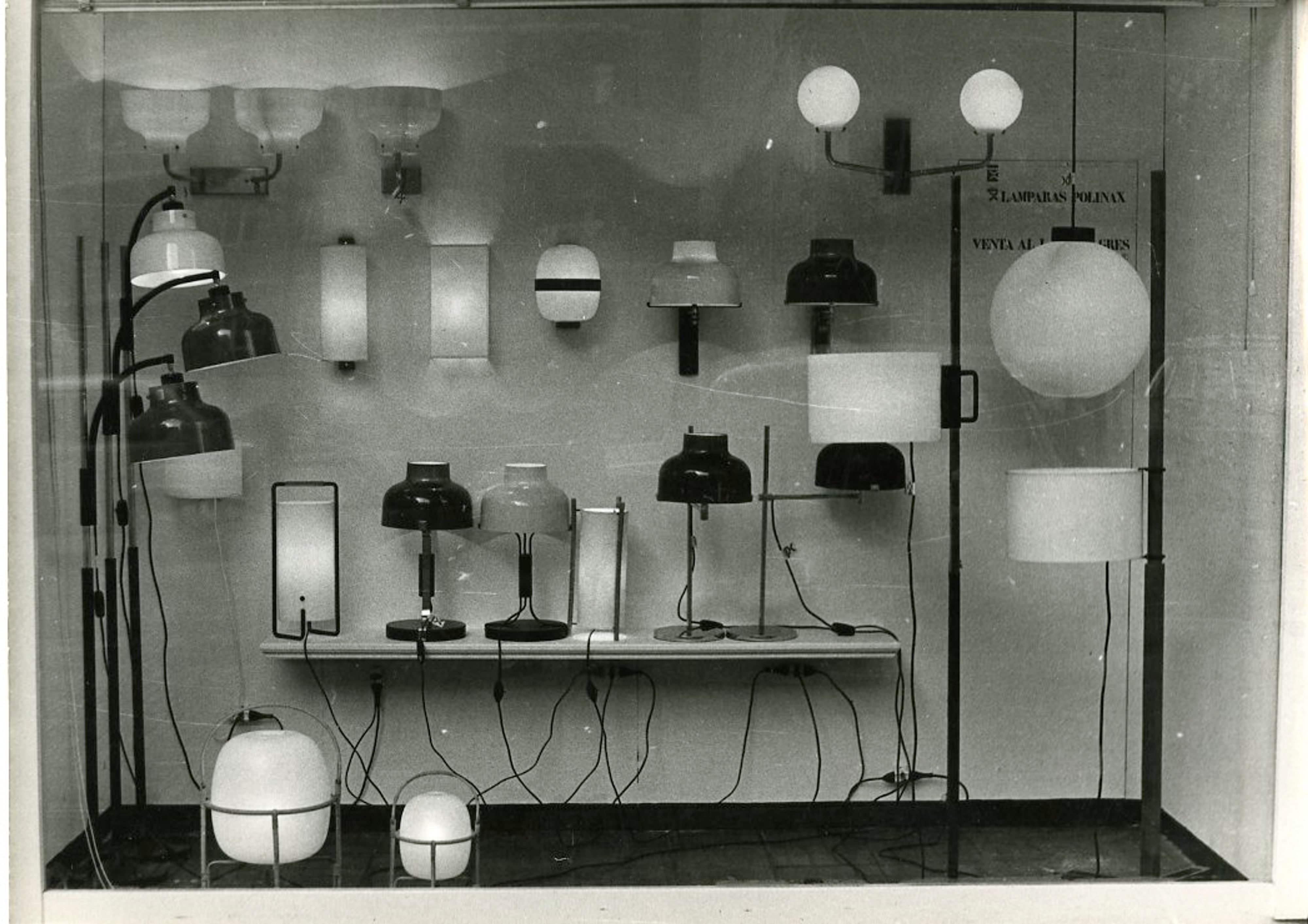

Exhibition view of Miguel Milà, (Pre)Industrial Designer at the 2024 Madrid Design Festival. Photo by Mercedes Pelaez; courtesy of the Madrid Design Festival.

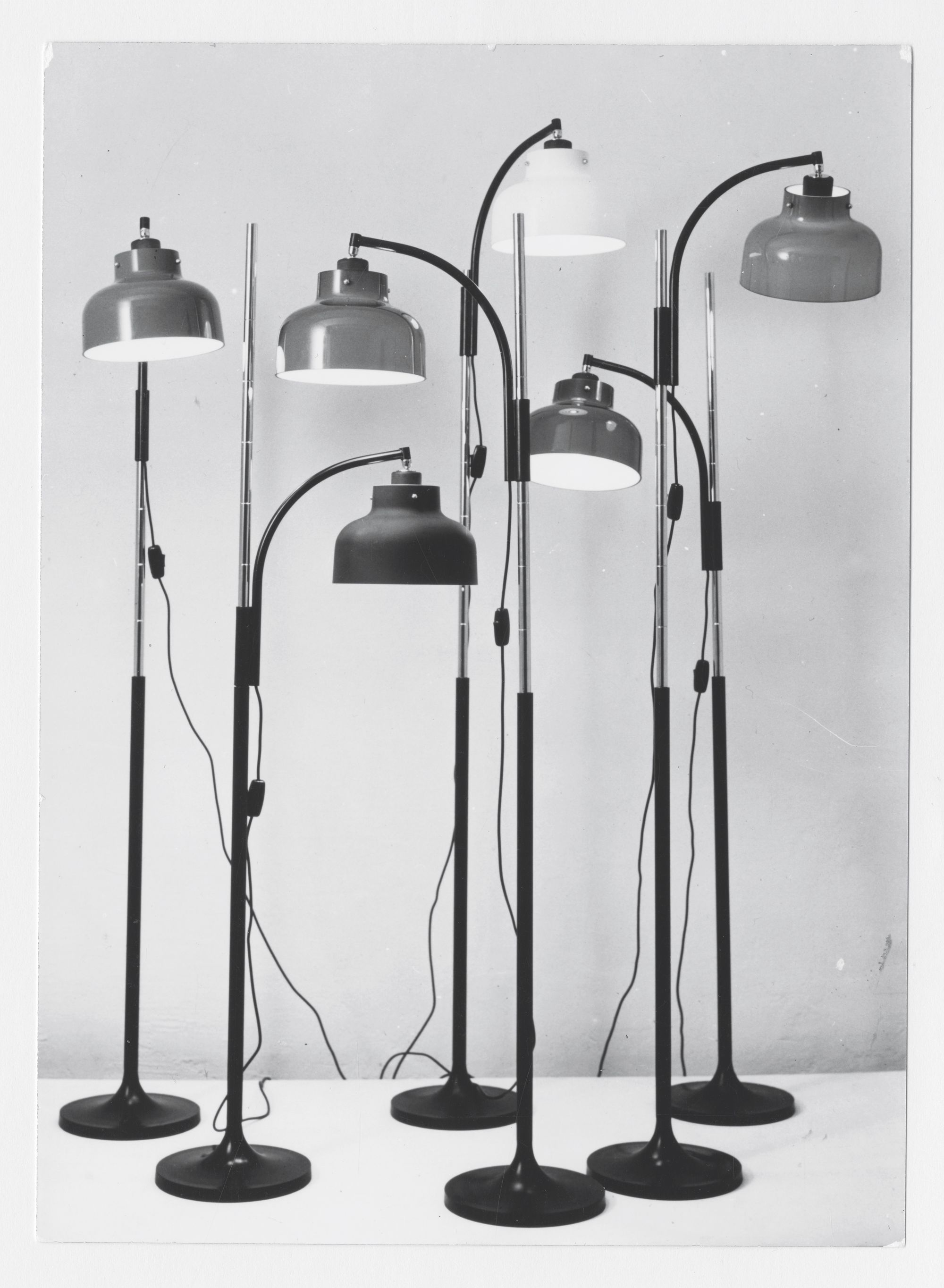

This mixture of quality and sobriety is a defining characteristic of Miguel Milà’s oeuvre, which combines the timelessness of Scandinavian design with a rather patrician Catalan cachet. Take his series of standard lamps from the late 1950s and early 1960s, each of which was a refinement of the one before. The first, the 1956 TN — which stands for tía Núria, since he designed it for the study of his writer aunt — defines the basic concept: a simple bulb and shade attached to a bracket that slides up and down an iron pole so that Aunt Núria could use it both at her desk and in her armchair. Though the forms are minimalist, the manufacture is complex, with many different parts, including rubber wheels that tended to get stuck. Over the next few years, with each new iteration, he refined and improved the idea, until finally he arrived at the 1962 TMM, in wood, with simple metal rings instead of wheels, and the number of parts reduced to barely a dozen. In the Fernán Gómez show, the lamps are displayed next to each other so that visitors can chart the evolution of Milà’s thinking, which was to a large extent based in the empirical observation of how his designs performed in real life.

Another long-term search for economy concerned his public benches, the first of which was commissioned for a 1981 revamp of Barcelona’s Plaza Real. Realized in wood and lightweight aluminum, making them much easier to install than the hefty iron objects of yore, their forms were designed for comfort after Milà observed an old man struggling to get out of one of the city’s low-slung traditional models. Over the years, he sought to reduce the amount of material used with each new model he brought out, culminating in the 2014 Harpo line of chairs, benches, and loungers, designed in collaboration with Gonzalo “to take up a mere tenth of the volume required by other benches of similar dimensions.”

Miguel Milà’s studio. Photo courtesy of Madrid Design Festival.

Miguel Milà’s Harpo chair. Photo courtesy of Madrid Design Festival.

At the time Milà started out, in the 1950s, Spain was just beginning to emerge from the autarky phase of Franco’s long rule, when contact with the outside world was limited and industrial production essentially non-existent — whence the exhibition’s title, Miguel Milà, (Pre)Industrial Designer. Núria Sagnier’s lamp, for example, was made in collaboration with the blacksmith who fashioned it, a process greatly helped by Milà’s own penchant for bricolage, a bug he caught during adolescence. Indeed many was the object or prototype he knocked up in his impressively equipped workshop, such as the bamboo-and-leather fly swatter he initially designed for his wife, who found the everyday plastic varieties unaesthetic.

Milà began his career working with his architect brother, Alfonso, who had set up in practice with fellow ETSAB graduate Federico Correa. “They lacked suitable lamps and furnishings for the interiors of the buildings they were constructing,” explains Gonzalo, “and Miguel, who understood architects, was able to design just what was needed.” Since 1950s Spain was not a land of plenty, the stripped-back interiors Milà produced were a function of both taste and necessity. Later, in the far more prosperous 1970s, when he fitted out houses and apartments for Coderch, the same sobriety prevailed, only with ostensibly more luxurious materials. Summing up the approach that has guided his 70 years in practice, Milà reminds us that “a chair is more often empty than occupied, a lamp spends more time off than on. My obsession is to make functional objects that, since they are often not in use, are also beautiful.”

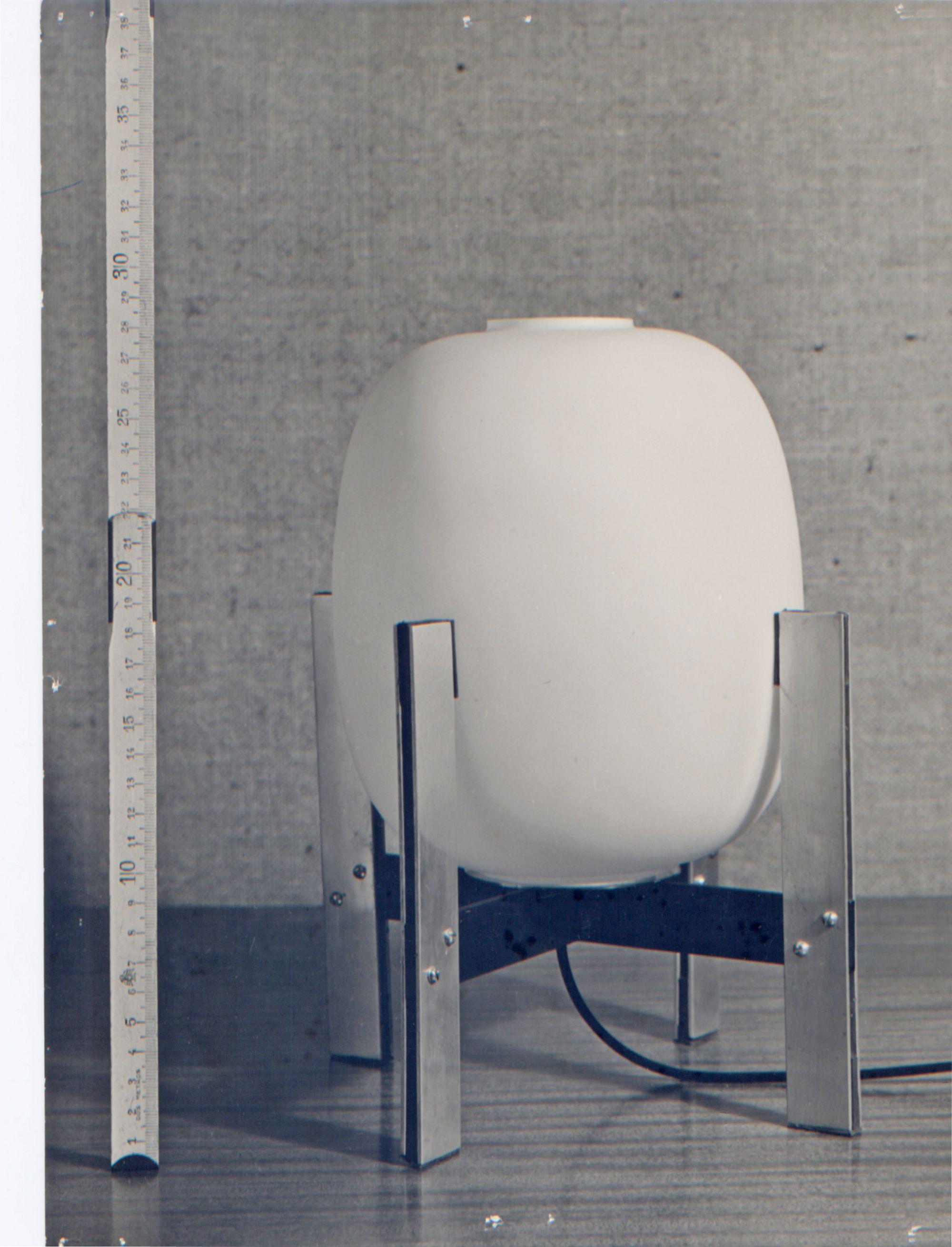

Cesta Metalica by Miguel Milà. Photo courtesy of Madrid Design Festival.

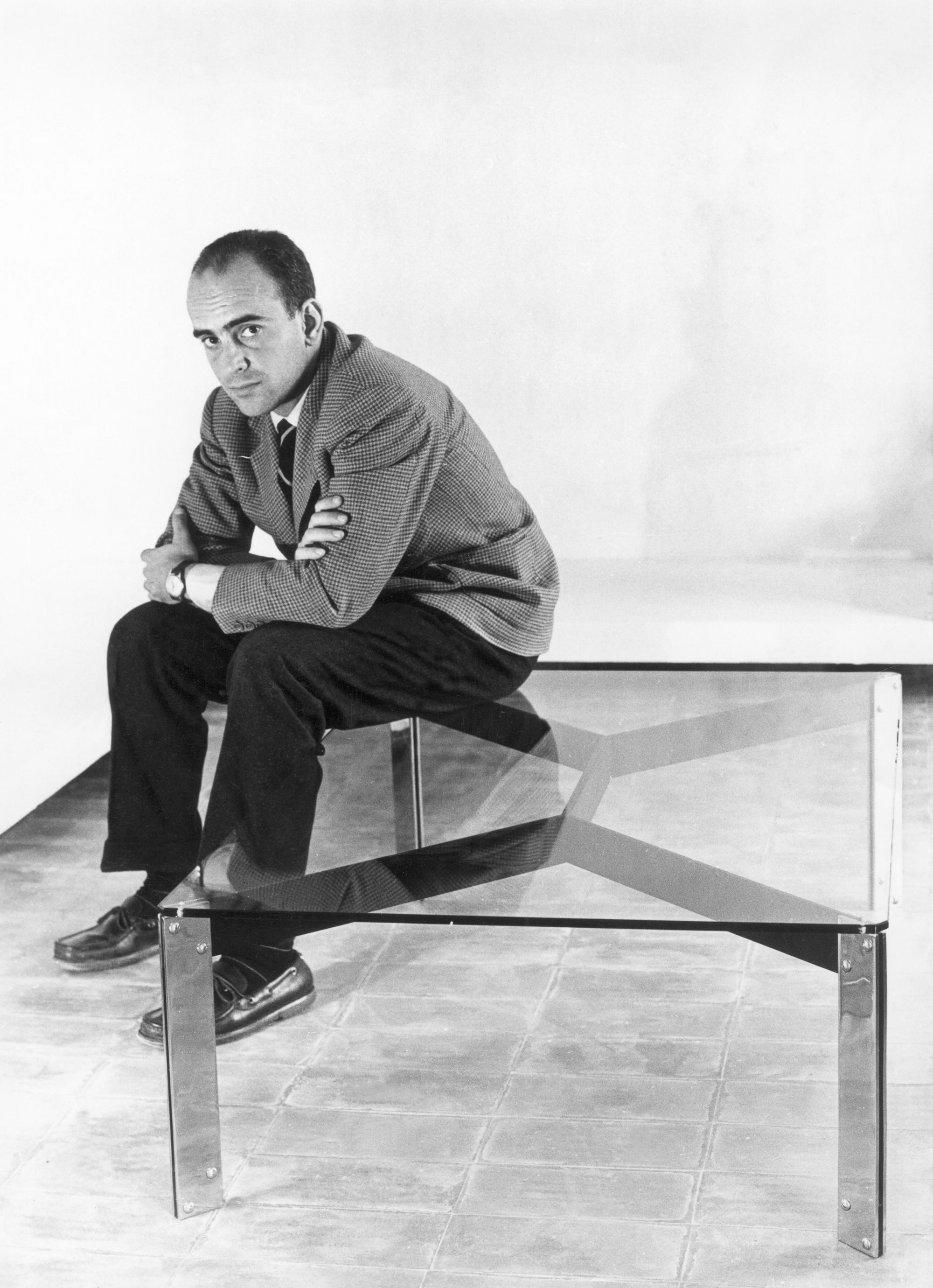

Miguel Milà seated on a glass table, circa 1961. Image courtesy of Madrid Design Festival.

Miguel Milà’s lamps. Photo courtesy of Madrid Design Festival.

Archival image of Miguel Milà’s studio. Photo courtesy of Madrid Design Festival.