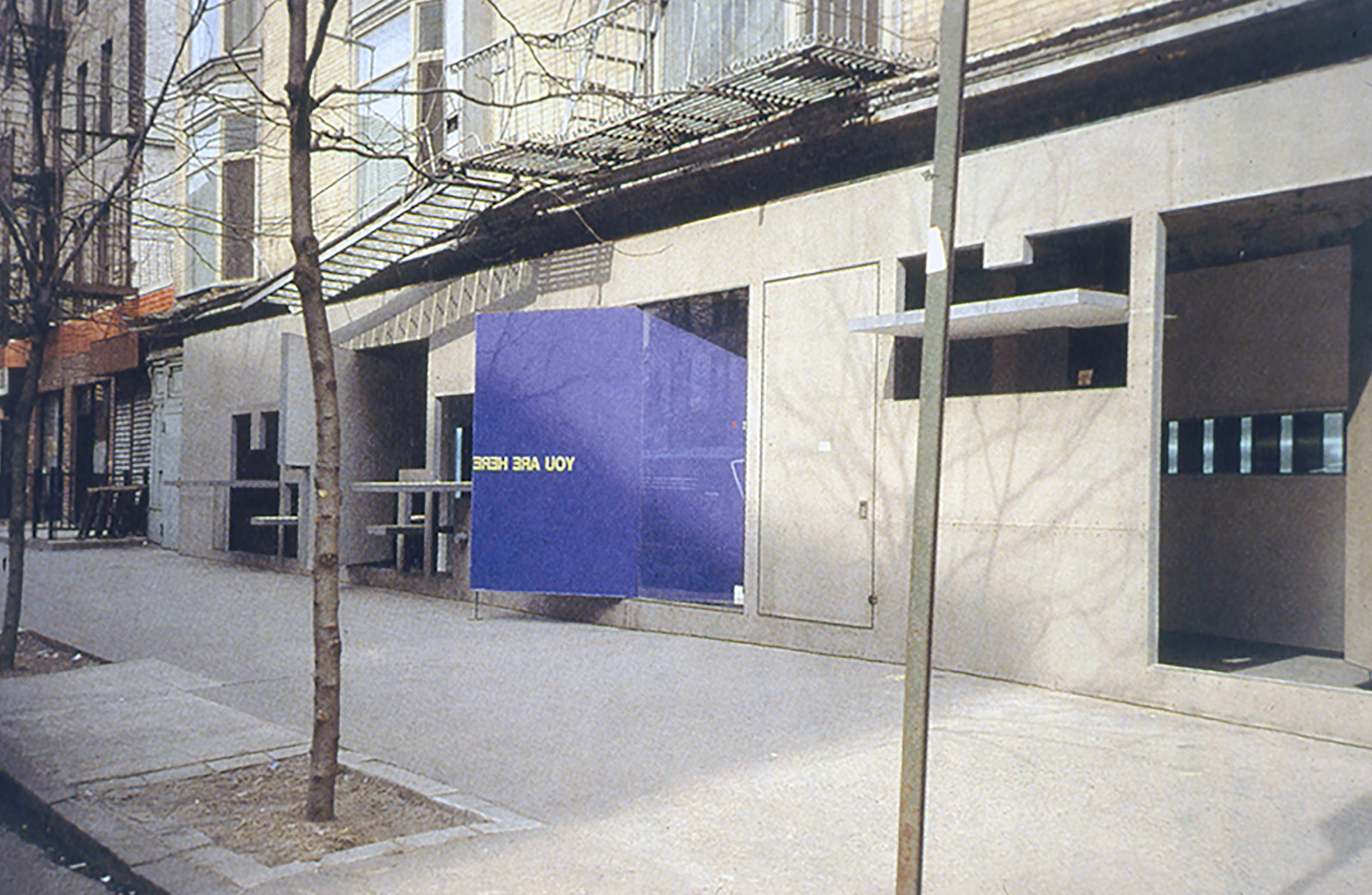

View of Laura Kurgan’s seminal show You Are Here: Information Drift, which ran at storefront for Art and Architecture from March 12 until April 16, 1994.

On the occasion of Storefront for Art and Architecture’s 40th anniversary, Nadine Fattaleh reexamines curator Laura Kurgan’s 1994 exhibition You Are Here: Information Drift in which Kurgan deployed novel technologies to explore the relationship between digital environments and built spaces.

In a short essay entitled My Atlas, Brazilian-Czech philosopher Vilém Flusser (1920–91) rehearses a conversation with his grandfather over atlases, the dominant mode of geographic representation in the pre-digital age. By way of his grandfather, the author discovers that objections to the atlas’s “orienting functions” triggered a crisis of confidence in the stability and certainty of modes of apprehending space. With newly proliferating loose paper maps of vertiginous lines, points, and polygons, “the conventionalism, the intention inherent in cartographical representation became apparent to the reader.” Flusser’s point is that cartography is not a neutral science, but a value-laden practice of representation marked by political motives and their associated pictorial rules. The result of this reckoning is an ambiguity at the horizons of possibility arising from the map’s evolving status. “My grandfather often told me that for him, looking at an atlas was like opening a door leading towards a dreaded and at the same time desired future,” Flusser recalls. “It allowed him to see into a future in which it would be impossible to orient yourself and in which art, science, and politics were melting together, just like they did on his maps.”

This simultaneous feeling of “terror and fascination” may have been the experience of exhibition-goers as they crossed the pivoting doors separating the bustling streets of SoHo from the gallery space at Storefront for Art and Architecture in the spring of 1994. Curated by Laura Kurgan, You Are Here: Information Drift was “a computer-based multimedia installation that sought to question the relationship between digital environments and built spaces by playing on orientation and disorientation in this interaction,” as Storefront’s website recounts. On the eve of the show’s almost 30-year anniversary (and 40 years after Storefront’s founding in 1982), at a moment in time when the Global Positioning System (GPS) has become a ubiquitous and opaque system that infiltrates countless aspects of our lives, there are many questions the show posed that are still worth considering today.

View of Laura Kurgan’s seminal show You Are Here: Information Drift, which ran at storefront for Art and Architecture from March 12 until April 16, 1994.

Exhibition photo from Laura Kurgan’s You Are Here: Information Drift.

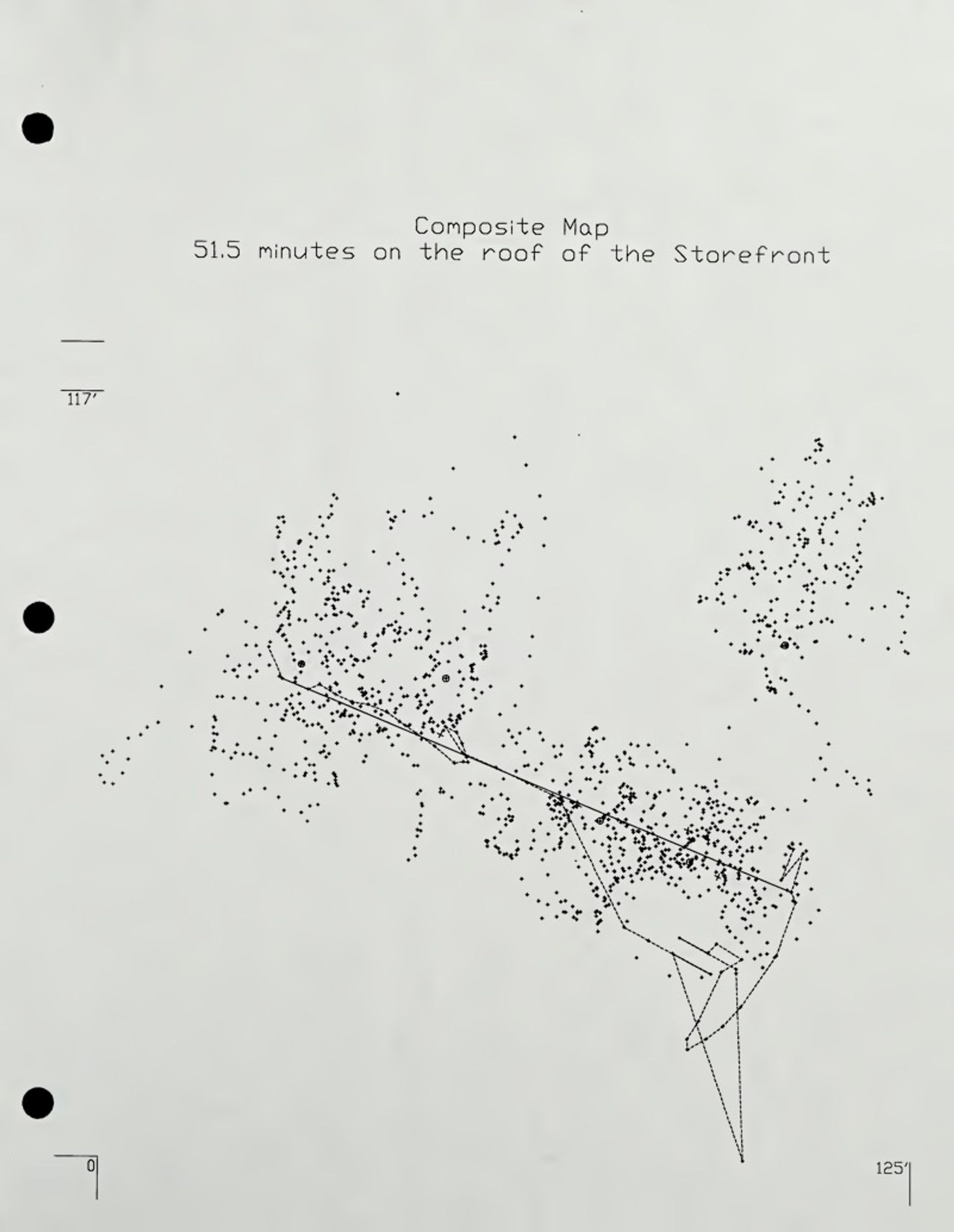

Kurgan’s installation and exhibition on GPS was exactly the theater of operation where art, science, and politics became intermeshed in the world of digital cartography. Via a portable GPS receiver fitted to the Storefront rooftop, which transmitted live location readings onto screens in the gallery space, a “map” was produced that did not take the form of a singular node indicating a definitive location, but rather a series of breadcrumb-like points that approximated a stability through processes of scatter, reference, correction, and average. The instantaneous data appeared on the Head-Up Display (HUD), a “spin off” interface designed to mimic the prosthetic navigation system that decked military-aircraft cockpits. The installation commingled a commercial receiver, first available on the market in 1991, and a military retrofit, used during the first Gulf War that same year.

With an ironic poetics of space derived from technical jargon and GPS promotional literature, and a slick, eerie aesthetic recalling military tableaus, the show bespoke the impossibility of geographic certitude in a world of expanding technologies of location. There was a precise literalism to the its central message: our lust for orientation has left us adrift in an amalgam of indefinite positions. The here always points to an elsewhere. But perhaps the disorientation experienced by greater exactitude can be understood as the loss of a moral compass, or the increasing impossibility of a politico-ethical bearing on the world.The political stakes of the show amounted to far more than what one contemporary review provocatively termed “geographic existentialism.” Today, few of us really understand the proliferating network of satellites, base stations, and receivers that allow us to determine our location. But the growing awareness that the devices we carry in our pockets are constantly transmitting private data to corporations and governments alike marks a shared feeling of dread at this unspeakable future foretold, in some way, by Kurgan’s exhibition.

Exhibition photo from Laura Kurgan’s You Are Here: Information Drift.

You are Here, as the press release noted, sought to trouble “the reassuring boundaries … between museum and society, public and private, human and machine.” Recently renovated at the time, the façade of Storefront, with its technical reversal of the spatial particulars of inside and out, accomplished part of this critique of the cardinal separation of the line. The drift of information staged through the networking of satellites in space, the receiver on the roof, and bits on a screen bore witness to the increasingly complex interplay between digital and cybernetic space and so-called real, perspectival positioning. But the most pernicious distinction that the show seemed, if only implicitly, to put on trial was the separation between the military and the civilian. “The infiltration of the military into cultural geography is deeper and more serious than the face value of its products, now self-mingling with domestic stuffs,” wrote Kurgan, explaining that the range of destructive uses of GPS in military target acquisition andmissile guidance had prefigured the promise of civilian conveniences related to location services in commercial aircraft or in-car navigation that are now ubiquitous.

By inverting this paradigm and placing a military artifact — the Head-Up Display — at center stage in the cultural space of the gallery, You are Here rendered visible the dark shadow of increasingly precise targeted killing exercised at greater distance alongside the promise of geographic exactitude. Was the effect of this juxtaposition meant to disclose the horrors of war to those shielded from its frontiers? I can’t claim with confidence, but the assumption, at least, is that revealing GPS’s place in the military-industrial complex would lead to reflection about the costs of geographic transparency.

View of Laura Kurgan’s seminal show You Are Here: Information Drift.

Looking back with the benefit of hindsight, You are Here appears to fit squarely within a genealogy of installations that seek to deploy the institutional mechanisms of the art world to scrutinize the imbrication of technologies of vision, display, representation, and space-making with militarism and imperialism that are distinctly, if not exclusively, American in nature. These questions seem to have caused, in recent years, a firestorm surrounding the twin patronage of the arts and the military in the works of diverse artists including Laura Poitras, Trevor Paglen, and Eyal Weizman and Forensic Architecture, among others.

To echo Flusser, the days when atlases were books must, indeed, have been very beautiful. But as maps and other military artifacts seep deeper and deeper into our everyday life, the question remains whether art can offer more than nostalgia for the days when it was easier to find our way around the world.