(LA)Horde, Age of Content, 2023; Photography by Blandine Soulage.

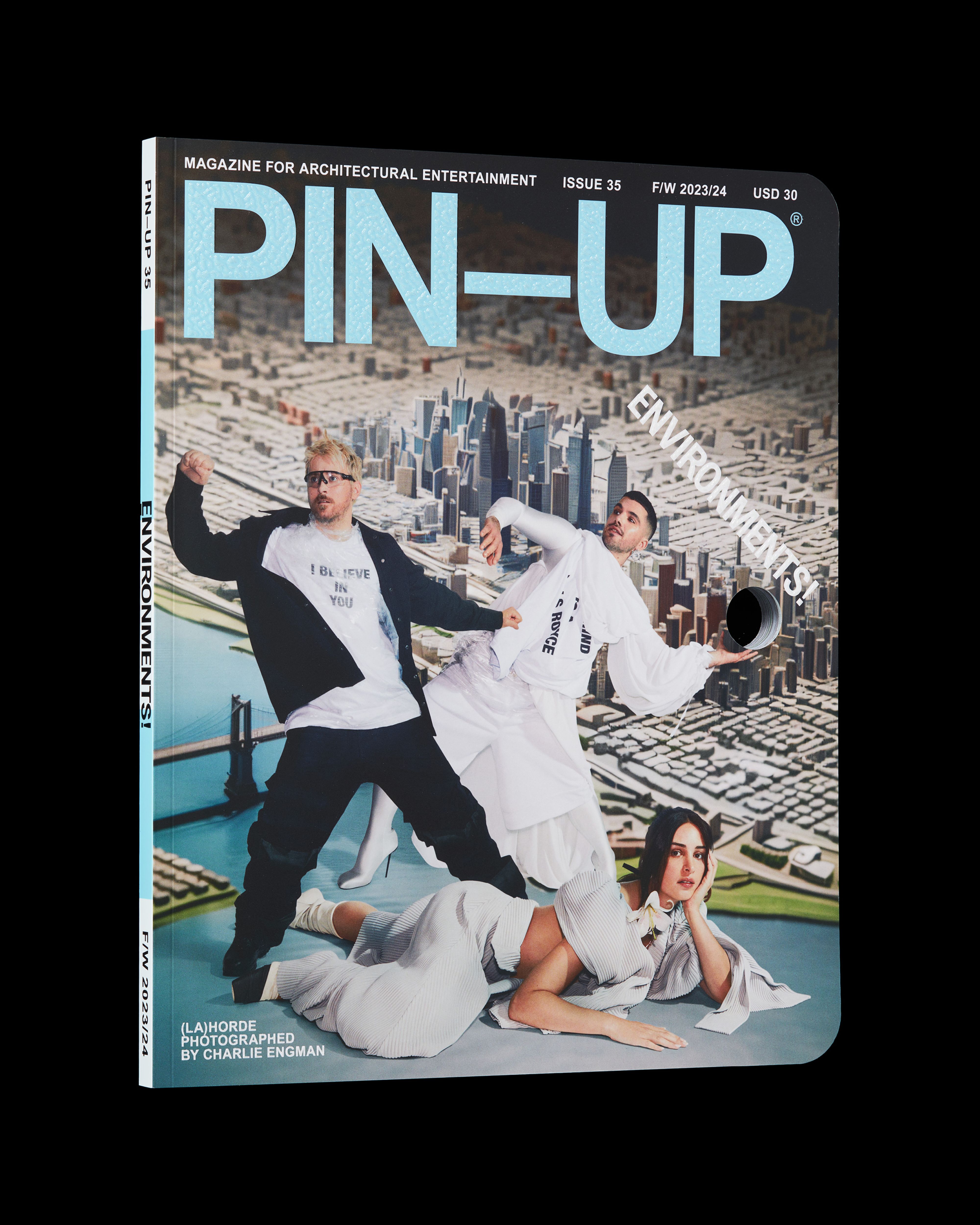

(LA)Horde photographed by Charlie Engman for PIN–UP 35.

When it débuted in 1972, the Ballet National de Marseille (BNM) surprised the world with Pink Floyd Ballet, a radically modern take on a classical form. Fifty years later, the BNM remains just as radical thanks to choreography collective (LA)Horde, who took over the artistic direction in 2019. Formed by artists Marine Brutti, Jonathan Debrouwer, and Arthur Harel in 2013, (LA)Horde ignores the distinction between the worlds of art and dance, flowing seamlessly between environments, deconstructing class signifiers embedded in movement practices, and applying a transgressive and psychologically intense approach to institutional structures. Besides working alongside figures such as Nicolas Di Felice of Courrèges, Glenn Martens of Diesel and Y/Project, the multi-disciplinary collective Groupe CCC, and the filmmaker Spike Jonze, (LA)Horde have also produced work for pop icons like Sam Smith and most recently Madonna. The collective has staged major BNM and non-BNM productions alike over the years, including Room With A View (2020), a frenetic tour de force that deals with societal and environmental collapse; To Da Bone (2017), both a performance and a documentary featuring jumpstyle dancers where real and virtual bodies blend and blur; Marry Me in Bassiani (2019), a staging of a traditional Georgian wedding produced with dancers from the Tbilisi-based Iveroni Ensemble; Age of Content (2023), another key example of the collective’s evolutive “post-Internet dance” approach, which redefines movement in the contemporary multiverse. In the spirit of the collective, all questions were answered in the single voice of (LA)Horde.

Cover PIN–UP 35, Fall Winter 2023/24 featuring (LA)Horde, photographed by Charlie Engman

Jesse Seegers: When you decided to come together, did you have a guiding concept?

(LA)HORDE: The idea was to create a house, both a roof protecting us but also a mental space where we can bring projects in and dissect them together. This is when we picked the word la horde. You know how there’s gender everywhere in the French language — from a chair, to the sky, to the moon — so we kept the feminine “la,” but put it in parentheses because we were already interested in a non-binary vision of the world and the idea that the question of gender was bigger than just the spectrum between feminine and masculine, a more nebulous vision.

JS: In your work there’s a range of scales at play: the smallest is the body; then there are the stage sets and locations for your films and performances; and finally there’s the planetary-scale distribution of your work online through digital media. Starting with the smallest, how do you bring fashion into your practice?

(L)H: We’re very lucky because we grew up with a community of queer people who were working in very different aspects of many creative fields. We frequented graphic designers, videographers, cinematographers, musicians, DJs, composers, and fashion designers. The designers we work with are very dear friends with a shared vision of how clothing is socially way more deep and interesting than is generally acknowledged today. When we create a show, the hardest part for us is to costume it, because it narrows the possibility of what we’re saying and gives a dancer a particular social identity. We’ve started working with Salomé Poloudenny, a Paris-based designer who shares the same perspective. She’s very experimental in terms of asking how we can create meaning through what the dancers are wearing and how the clothes serve both the subject and their dancing. For example, in Room With A View, all the clothing is upcycled, because we thought it was very important when we were talking about environmental collapse that we “dig” — you can’t necessarily tell, but it all came from thrift and secondhand shops. Salomé is amazing, she’s so smart and precise, and has contributed a lot to the construction of an identity for us. For Age of Content, we worked a lot with Glenn Martens at Diesel — it was fun to work with a friend, and also with a much bigger company.

(LA)Horde, Age of Content, 2023; Photography by Blandine Soulage.

(LA)Horde, Age of Content, 2023; Photography by Gaëlle Astier-Perret.

JS: You describe your work as “post-Internet dance” — what does that mean?

(L)H: We invented this neologism by mistake when doing our first interview. It was with a dance blog, and we were trying to describe our approach. Because we were already so interdisciplinary and belonged to the field of contemporary art, we adapted a term already very common in the art world, “post-Internet art.” There was this new understanding that even if people are independent artists, they are part of a bigger dialogue, and what happens to be out there in the world is a result not only of synchronicity but also the fact that we’re all tuning into the same frequency and thinking about the world more collectively. It’s given rise to new aesthetics, though that’s not what we’re interested in here, rather that the work process is more collective. Our idea of post-Internet dance was an acknowledgment that the new tools we have today to share movement will impact how choreographers develop their work.

JS: That’s really interesting, because in your older work, for example Tout commence par une gavotte [Centre Pompidou, 2015], we can look back at that moment around 2015 as the last gasp of the promise of web 2.0 social media. The Arab Spring being an example of, “Social media is great, look what it can do for people!”, but then we were like, “Oh shit” — with phenomena such as Brexit and Trump, alternative no longer means punk but alt-right.

(L)H: We were always aware of these two sides of the coin. We refer to a saying by Michel Foucault, originally from Paul Virilio: “The invention of the ship is the invention of the shipwreck.” Today we have more background, so to any terrorist attack you can say, “What happened before which created an environment where people wanted to retaliate?” We have so many more perspectives on everything, and are completely lost in the chaos of reality and different points of view. It’s not that the world has become more complicated, it’s just that the tools we have today make the chaos more visible.

(LA)Horde, Age of Content, 2023. Photography by Gaëlle Astier-Perret.

JS: I love the way you phrase it: “making the chaos more visible.” It feels like an important element in your work. Often there is violence — for example the question of police brutality — sometimes represented explicitly and at others alluded to more subtly. These references are frequently juxtaposed with very gentle motions, heightening the contrast. The performance makes the chaos more visible in a way that reveals it was always there.

(L)H: This is exactly what we’re trying to experiment with in our new show Age of Content. How can we remain critical, and how do we react to the amount of different — and paradoxical — information that flows through us? But it’s hard even to understand whether our perception of the world is real. This is where we remain very humble by insisting that this is just our perception. This is what our interaction — physical, mental, and visual — with the world is, and these are the questions we want to address collectively. Our work is not a declaration; it’s an invitation to observe what we gathered from the world. When we want to describe Age of Content in a nutshell, we say it feels like an existential crisis through a doom scroll. We rid ourselves of completely building a narrative because we’re very aware of the multiverse we’re living in, aware that human beings are living in alternate realities.

JS: In the classic live theater setting, people don’t have their phones out, but you bring Internet-native ideas into the theater. The Internet is still lurking there, almost like the walls are made of the falling green computer code from The Matrix.

(L)H: There are many things here. First, a very interesting book, Computers as Theatre by Brenda Laurel [Addison-Wesley Publishing Co., 1991]. For example, in theater we use the term “the fourth wall” to refer to the liminal space between what is happening on stage and in the audience. In cinema, the fourth wall is breached when those being filmed look at the camera. So first we have theater, second cinema and video, and third digital technology that is taking theater, but also cinema, and putting it in a device where people are alone in front of a screen. Our work has been seen by more people online than ever in real life, which has created a permeability between our online audience and those who come back to the theater to have a different experience of it.

(LA)Horde, Marry Me in Bassiani, 2019. Photography by Jean-Michel Blasco.

(LA)Horde, Marry Me in Bassiani, 2019. Photography by Jean-Michel Blasco.

(LA)Horde, Marry Me in Bassiani, 2019. Photography by Aude Arago.

JS: Watching Room With A View in Aix-en-Provence, I don’t think I’ve ever seen that many young people, even teenagers, so excited to attend a ballet performance. There’s a concept from Raving by McKenzie Wark called “ketamine femmunism,” which she defines as:

“a collective state emerging out of a constructed situation from which masculinity that expresses itself as domination is subtracted as technically obsolete. Achieved in part by reparative discrimination. It has no necessary ongoingness, memory, or relation to desired futures, and appears only momentarily. Where girls and the familiars get their rave on, where ravespace, enlustment, and xeno-euphoria can happen among them. Not utopian as it can still all go wrong. It touches the surround.”

For me, seeing Room with A View from the outside feels like how I’ve felt that concept internally at raves, both in the ways the dancers move together, but also your quarry stage sets where one can imagine an illicit rave happening.

(L)H: It’s interesting how ketamine has become a subject again, because it’s about dissociative behavior and feeling, and you also have alternative-reality acid trips becoming more popular. Each era has its drug, and now people are letting go of cocaine for more peaceful kinds of substances. Cocaine is really the drug of psychoanalysis and capitalism, and we’re interested in what kinds of breakthroughs we will have with new, different uses of these substances. For example, the last section of Age of Content is a crazy medley of TikTok, jazz, and Postmodern formations set to Philip Glass music. It’s a cacophony of situations, and we call it a dopamine hit.

JS: That’s a nice segue into your set design and how it works with the other elements.

(L)H: In Room With A View, we wanted to give context to the movement we were making — first off, because we are multidisciplinary artists and the idea of installation and creating a sculpture which the dancers navigate was interesting, but also to make them a little bit less abstract and to anchor them in a narrative. This is not an especially fictional narrative, but more a chain of thought, a reflection we have together where we can tell each other stories, without one being more valid than another. The environment was a subject we wanted to address, but we were very wary of greenwashing, and acutely aware of what it means today to make an ecological show. The moment we cracked the code was when we said, “Instead of just talking about the environment, we’re going to talk about collapse, and the aesthetics of collapse, because collapse can also be virtuous.” Of course, the collapse of the ecosystem is horrible, but the collapse of patriarchy is a good thing, and somehow these phenomena are happening at the same time. When we called the show Room With A View, we were amused by the fact that it’s a hashtag for luxury hotels and that these kinds of music environments were also created for this audience of very privileged people. We were thinking about the festivals that happen in Sweden where you’re in a concrete bunker or a marble quarry, and this was the start for us, because marble is used to create the most exquisite artworks but also the most luxurious toilets. There is something special about its having veins — of all the different types of stone, it’s the most flesh-like, and that’s why it was used a lot for sculptures. When we started thinking about marble and its very paradoxical use, we rediscovered Michelangelo’s idea that the act of sculpting liberates the body from the block. For us it felt very much like what we were doing when creating choreography: shaping it little by little to give it the form we imagined.

(LA)Horde, Room with a View, 2020. Photography by Aude Arago.

JS: That’s a very interesting way of thinking about creation across disciplines.

(L)H: When we came up with the idea of a marble quarry, we started to think maybe we could do a sort of photogrammetry of a grotto or a quarry, scanning the environment like on Google Maps so you get this shape of a mountain or building, a process that always ends up with residual artifacts. That’s why there’s this replica marble cutter that moves about on stage during the show. There’s also another analogy. The dance school in Marseille where we created the show was built by the architect Roland Simounet in 1992 — it’s a massive white concrete bunker with very few windows that feels a little bit like the Millennium Falcon from Star Wars. The use of marble was also a reaction to us entering the institution being able to construct something within that kind of building. So there were many conceptual entries into the marble quarry — from the music world where the festivals happen to the institution and the building in which we created it. All of these together are the kind of environment that we like because it provides a multiplicity: they’re not just one thing; they’re conceptually 5,000 things at the same time.

JS: Your work is like a set of transparent matryoshka dolls, with the kernel of the project being projected outwards, taking different forms with different resolutions, different media, and different ways of being perceived at different scales. But there’s still this little doll in the center that’s the core.

(L)H: Yes. The project most like that we’ve done so far is the one with the jumpers. It’s an insane story. After seeing jumpstyle videos, we contacted some of them online. In 2014 we got an opportunity with the Biennale Internationale Design Saint-Étienne — the curators, Elsa Francès and Benjamin Loyauté, offered us this huge, abandoned factory, and we were like, “Oh my god, this is wonderful, let’s build a stage here and have the audience watch something.” But as we were shooting videos on our phones, we realized it was very cinematic, and we also wanted to shoot a video there. The jumpers we contacted in France were from post-industrial zones, mainly in the region of Saint-Étienne. We were creating a new theater in a post-industrial environment in an out-of-use factory, and suddenly it started to click. These were all men from relatively modest backgrounds who were the new Internet workers. One guy was installing the cable for the Internet; another was in cybersecurity trying to identify pedophile behavior online. Guys who, in the past, would have been designated by class to work in factories were now Internet workers, and we brought them back as ghosts into the former industrial environment. They were shy about showing their true faces, so we anonymized them with masks, which was also a way of talking about their online avatars.

JS: You’ve used masks in other performances as well.

(L)H: This was the first, but after that we created a ten-minute performance for a contest in which we won second place. People were like, “We wish we saw the movie,” so we did a one-hour show, and we were filmed by friends, Laure Boyer and Édouard Mailaender, who did a documentary about us making the show called To Da Bone. So at this point we had a film, a ten-minute performance, a one-hour performance, and a documentary about it all. Then we started to re-enact parts from different works in The Master’s Tools, an ongoing project [begun 2017] where our relationship with these dancers takes on multiple forms and the content finds new shapes as we change the container.

JS: Maybe 20 years ago someone like Hal Foster would have written about the Postmodern flattening of “low culture” and “high culture,” a divide that’s inherently classist. But it’s an inheritance from these legacy institutions, right? Ballet is high culture and somebody doing jumpstyle online is low culture. This story reflects the past ten years of context collapse and flattening. The fact that the dancers were also the workers creating the physical infrastructure of the means through which they could then disseminate their images informs how we understand culture in a larger sense. High/low has become an obsolete distinction, and there’s a flattening of roles, values, and the socioeconomic conditions they emerge from and describe. This shift, which you’re both responding to and feeding, breaks down some of these class barriers and the inherent classism that comes with them.

(L)H: And you can ask yourself, is it flattening or merging? Or fusing? Because this flattening is multi-dimensional when you’re talking about the dancers and how they do it through their bodies. We refer to them as thinkers of the body, by which we mean that our body is not just a vessel for our mind and soul but can also think for itself. Because of the dissociative vision we’re starting to have with online news, with drug use, with all these kinds of things, it’s natural that people are so driven into dance now. We’re trying to get a grip on our humanity through flesh, and there is an awakening understanding that, rather than just a carrier, the body is an interface to the world.

(LA)Horde photographed by Charlie Engman for PIN–UP 35.