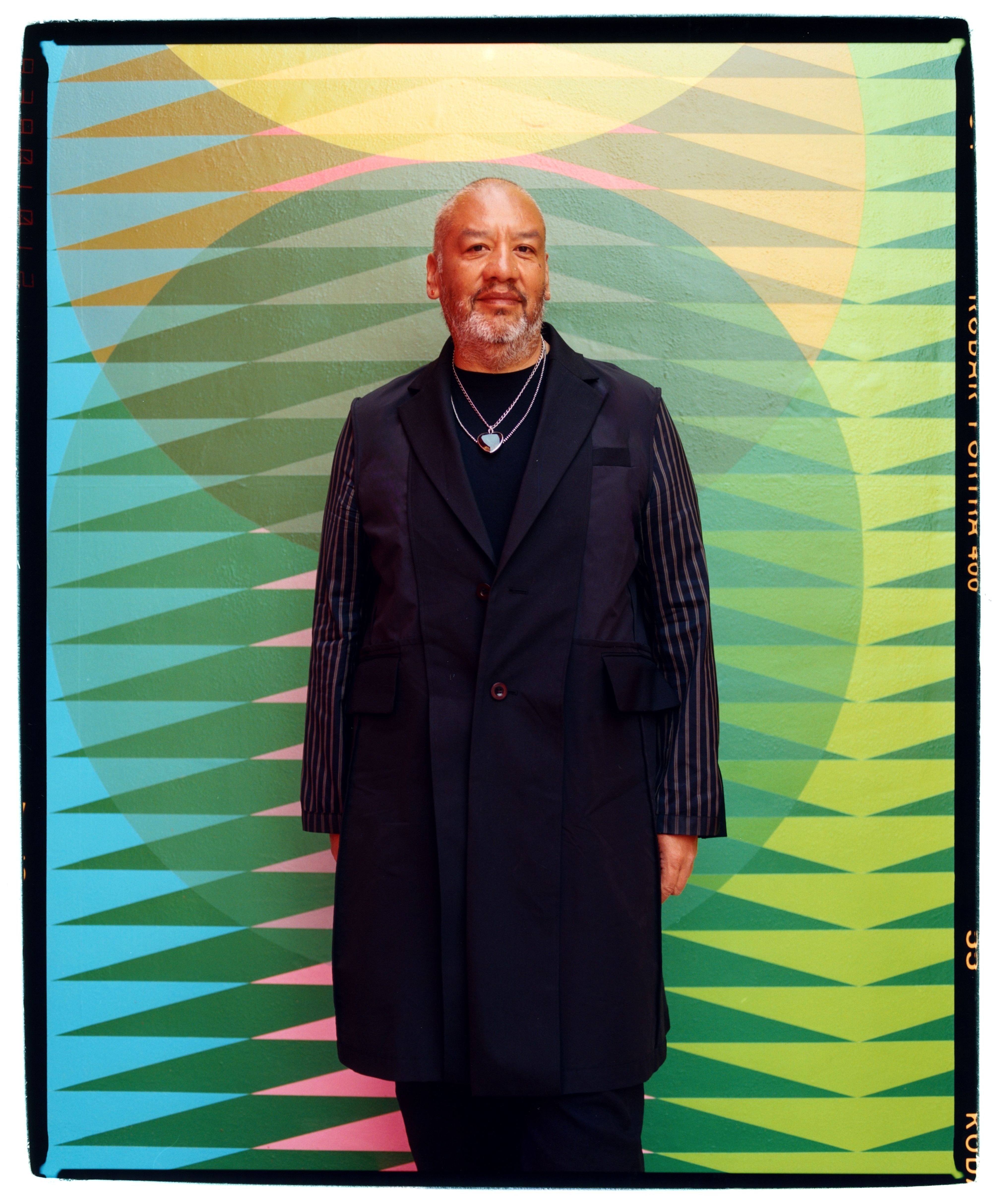

Portrait of Jeffrey Gibson on top of his sculpture, the space in which to place me (2024). Photography by Joshua Woods for PIN–UP.

Jeffrey Gibson photographed by Joshua Woods for PIN–UP.

Jeffrey Gibson, the first Indigenous artist to represent the United States at the Venice Biennale with a solo presentation, pedestals Native American history in contemporary art so profoundly, the near century-old pavilion’s Palladian veneer shakes loose. His career is equally bursting at the seams, with two major upcoming commissions — one opening later this year at Mass MoCA, and another at the The Metropolitan Museum of Art next fall. In Venice, Gibson presents his signature style of prismatic acrylic paintings alongside beaded figurative sculptures and statuesque busts. With works titled instructively, such as IF NOT NOW WHEN and Treat Me Right, the resounding pieces echo primal moments in Native American resistance, casting a new light on Indigenous futurity. If the space in which to place me is an answer, what was the question? Gibson responds: “It’s where I belong.” Born and raised in Colorado, and now living in Germantown, New York, the multidimensional artist represents the United States with a dignified humility: “I feel good about it, I feel good about it.” As we speak big art and beauty, the artist, constantly observing his surroundings, ensures visitors don’t fall too hard for his larger-than-life paintings, flags, and sculptures — literally.

Vere van Gool: In politically charged times, artists often turn to abstract and monochromatic works. And then there’s Jeffrey Gibson to exuberantly paint an entire pavilion in bright enamel. What does color mean to you?

Jeffrey Gibson: Color has inherent meaning. There’s passion, anger, hatred, and love. I think that the way I use color is very much metaphorical —it’s about abundance. It’s a lens that shifts the way we see things and multiplies perspectives.

Exterior view of Jeffrey Gibson’s exhibition for the United States Pavilion of the 60th Venice Biennale, the space in which to place me (2024). Photo by Timothy Schenck.

Installation view of WE HOLD THESE TRUTHS TO BE SELF-EVIDENT (2024) in Jeffrey Gibson Gibson’s exhibition for the United States Pavilion of the 60th Venice Biennale, the space in which to place me. Photo by Timothy Schenck.

How does it feel to represent the United States today?

I’m 52, so I’m not super old, but I do feel like I’ve gone through a few things in the world. I’ve seen and experienced certain political things.. Being a queer person, my understanding of the AIDS crisis — meeting people who were living through that and thinking about how artists used their work as political tools — has shaped who I am. We face so many challenges as a nation and as a human species right now. My hope is that this is an invitation to understand how putting down some of the things unnecessarily occupying our time and attention will only help us.

In what way do you hope your work and presence at the Venice Biennale will shape Indigenous culture?

You have to let Indigenous people lead, which just simply means standing back and giving them the space and opportunity. Just listen and let lead.

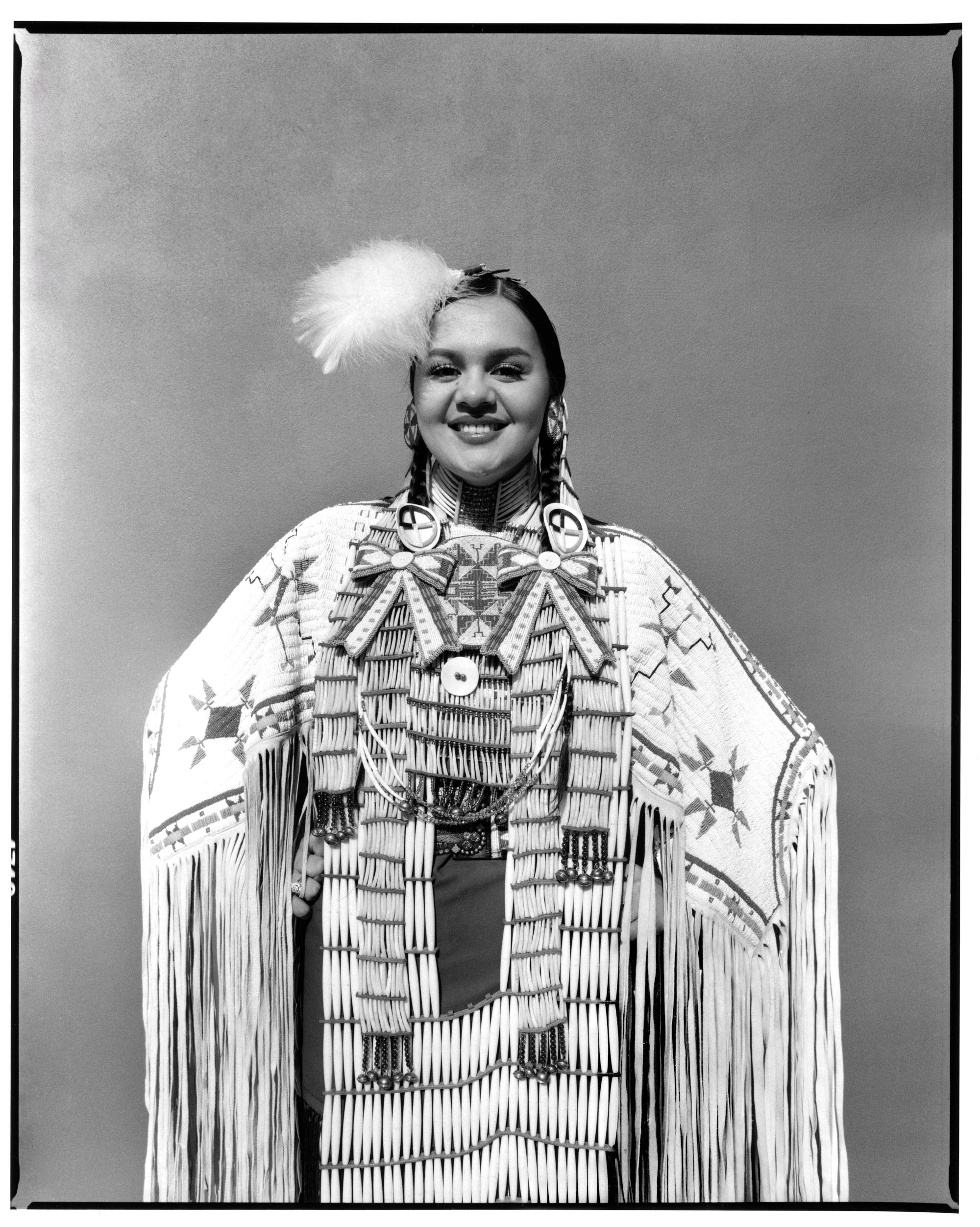

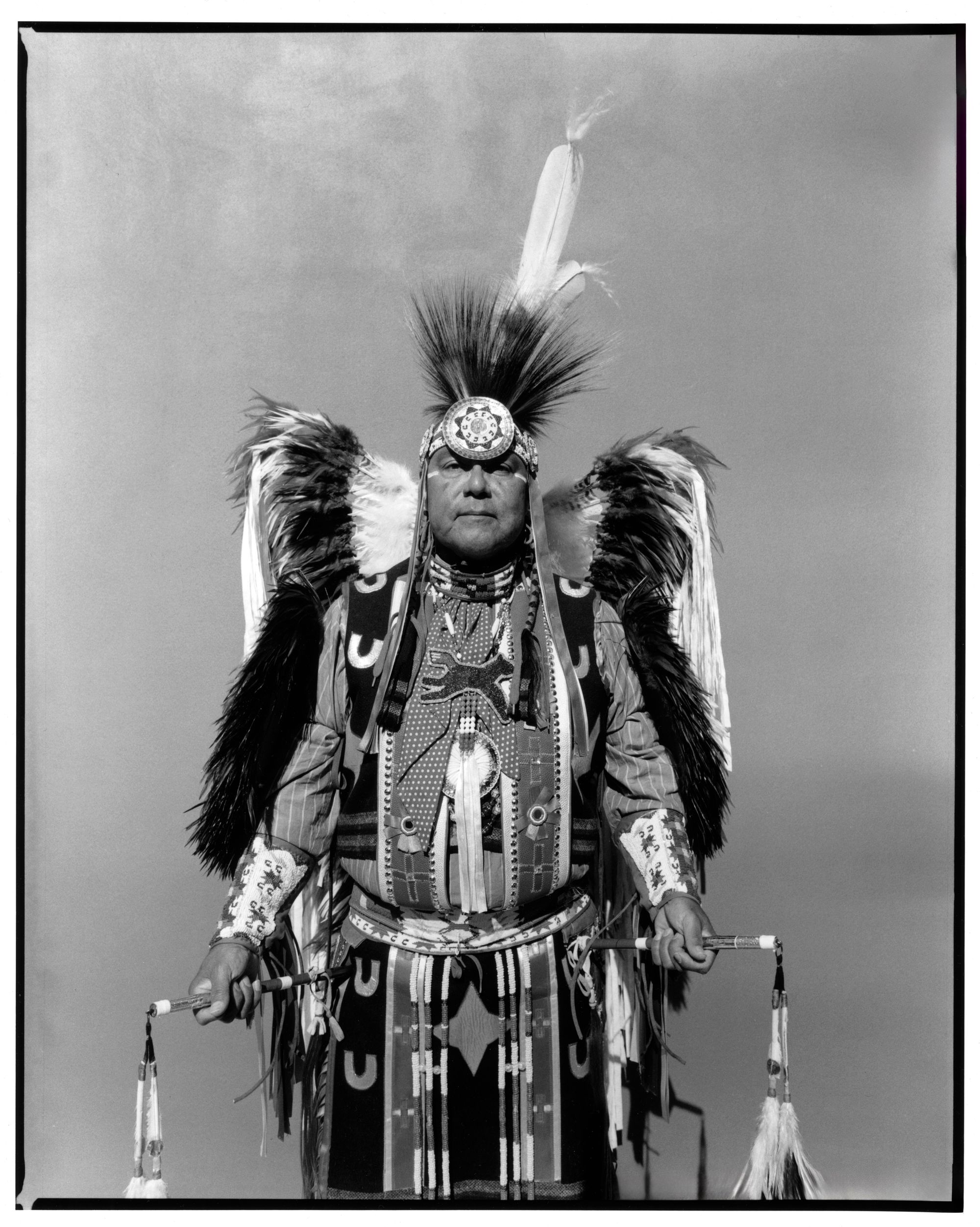

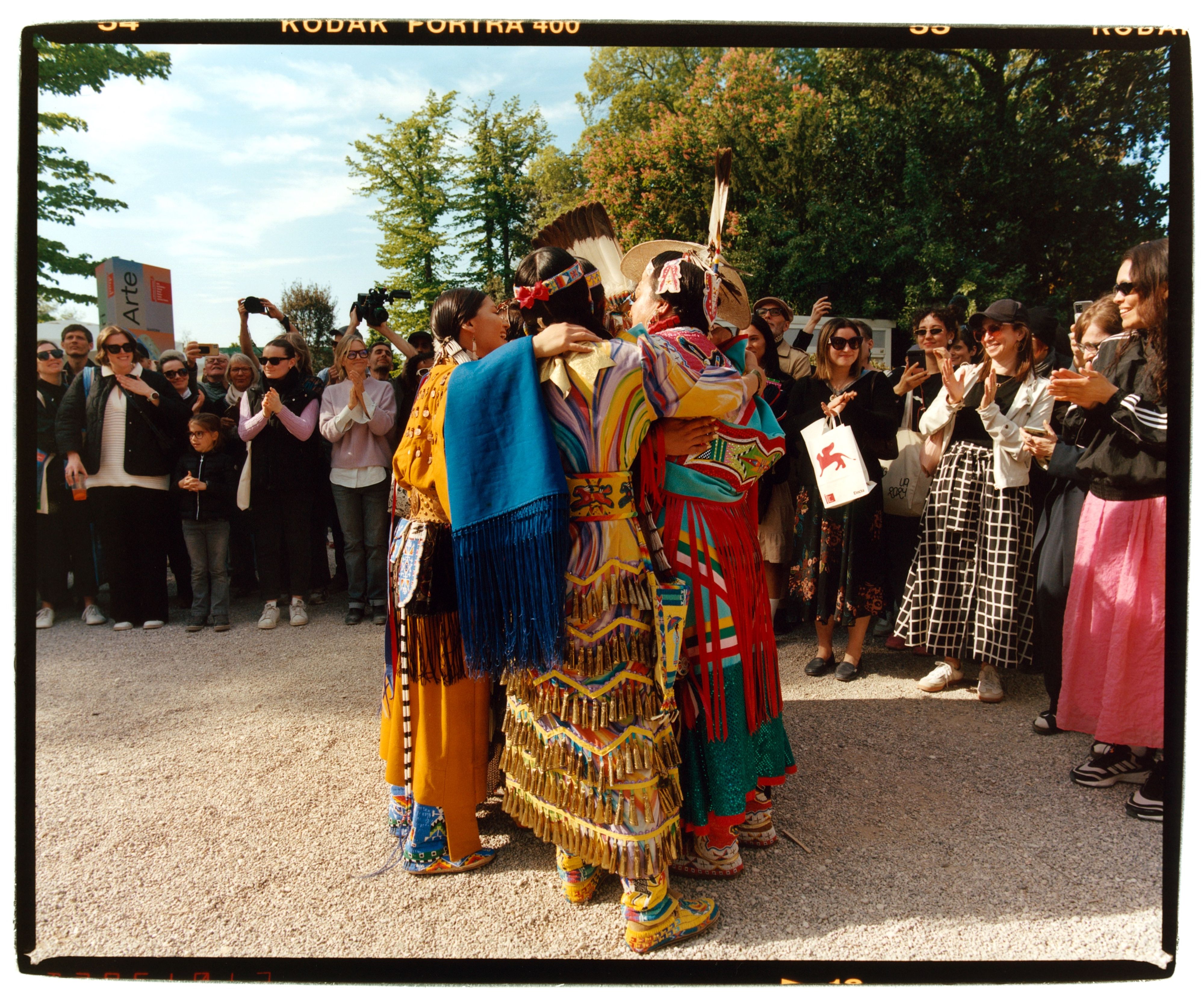

Throughout his career, Gibson has embraced abundance. Challenging viewers to see the world through his “riot of color,” in Venice, Gibson’s unabashed use of materials manifests as an amalgamated bright red pedestal marking the entrance of the space in which to place me. The interactive sculpture, a homage to Indigenous matriarchy, hosts the Jingle Dance. Performing in bright attire, a group of Native American decorated with beads and metal ornamentation swarmed the Giardini to call upon ancestors for strength.

Portrait of Jeffrey Gibson on top of his sculpture, the space in which to place me (2024). Photography by Joshua Woods for PIN–UP.

Detail view of Jeffrey Gibson’s WE HOLD THESE TRUTHS TO BE SELF-EVIDENT (2024). Photo by Timothy Schenck.

Photography by Joshua Woods for PIN–UP.

What does the Jingle Dance mean to you, here in Venice, today?

This jingle you hear is the lid of a tobacco container, something that others might just throw away. The story of the Jingle Dance is as follows: there’s a dream of someone who envisions women adorning dresses, and the sound of movement heals their granddaughter from illness. What I think is so interesting is that the lid, something that could have so easily just become refuse, suddenly gets transformed by another culture into something that supports their belief system. At this point, many people, myself included, perceive the Jingle Dance as a ceremonial dance.

The writing for the space in which to place me, which features the word love twice, ends on the note: “We never dance alone.” Who do you want to dance with the most?

Leigh Bowery. Absolutely. Leigh Bowery’s performances taught me about my own body — we were the same size. To see somebody be able to just go into the streets with reckless abandon, hanging upside down — I think he was an incredible person. And what was his outfit? It was skin.

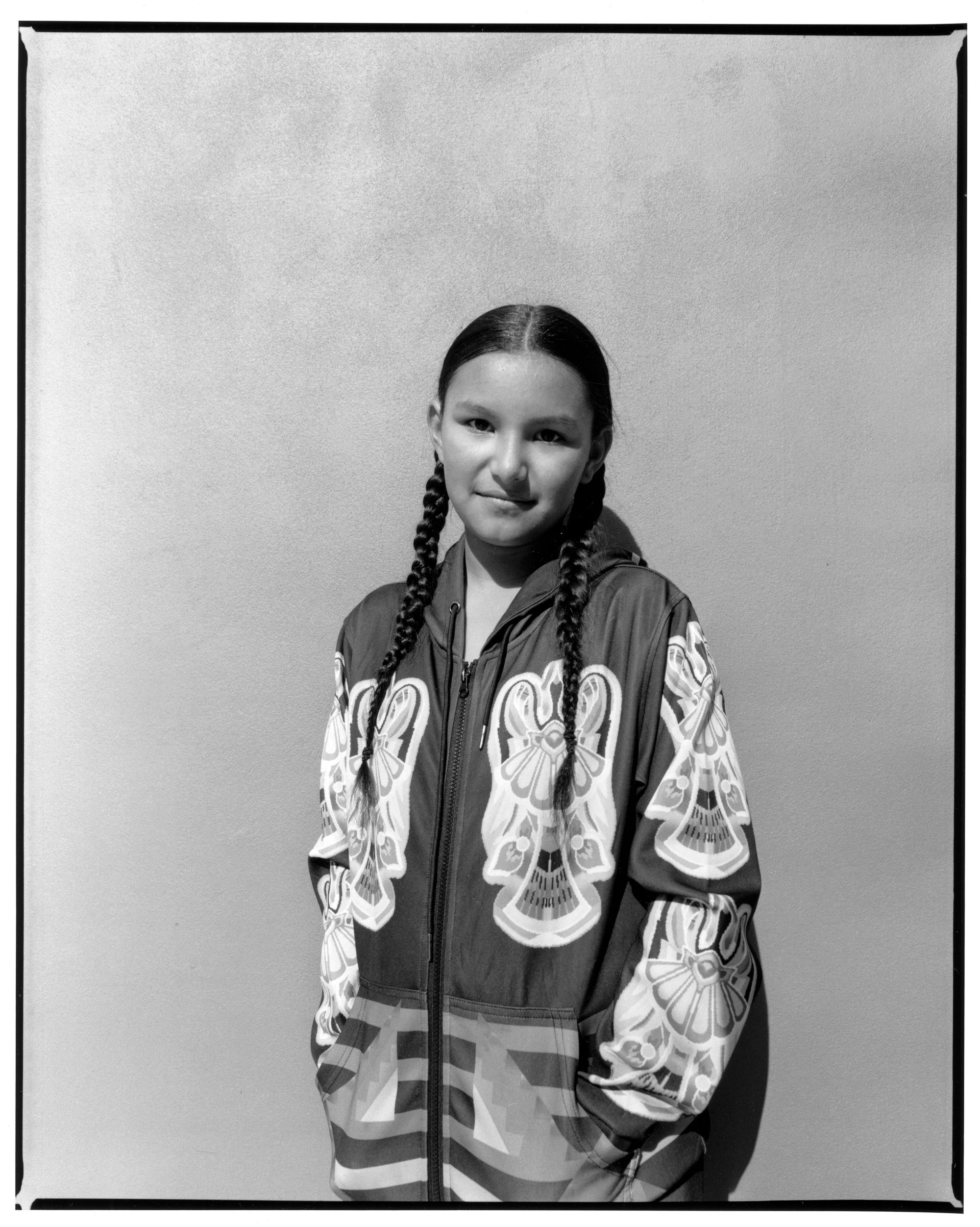

Gibson, who sees the present and future interwoven with the past, perceives Indigenous aesthetics as a root of cultural survival: “It’s like you have to spend the time to learn what was lost, so that you can build upon it to move forward.” When asked how knowledge can shape community, he responds: “For a lot of Native cultures, there’s disruption in our cultural lineages. Stories weren’t told, and knowledge has not been passed on. I always think about how much effort goes into regaining that.” How does this affect him personally? “If information had never been lost, I wouldn’t still be learning how to develop authorship of where we are now to continue forward.”

Photography by Joshua Woods for PIN–UP.

Photography by Joshua Woods for PIN–UP.

Photography by Joshua Woods for PIN–UP.

Photography by Joshua Woods for PIN–UP.

How do such unknown histories influence your relationship to authorship?

I grew up in a time where there was a lot of appropriation. Being a native person and having worked in museum collections and on the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, I began to think about what it means to use the work of somebody else or to refer to somebody, ethically. It kicked me into making sure that everybody is credited when we know who did it, and also making sure that I wasn’t copying anything or anyone. Ideas will sit in my head for years before they start showing up in the work.

After the Venice Biennale preview days, a three-day stint for art world frequent flyers, Gibson’s site-responsive pavilion and position will be open to a different audience: tourists. An expected 900,000 visitors will visit the Biennale in 2024. When asked about an unexpected inspiration behind his pavilion, Gibson falls silent: “That’s a good one. I don’t know. Part of it has to do with the fact that this pavilion came together so quickly and clearly in my mind. Certain things might be surprising to other people, but it’s difficult for me to decipher that.”

Exterior view of Jeffrey Gibson’s exhibition for the United States Pavilion of the 60th Venice Biennale, the space in which to place me (2024). Photo by Timothy Schenck.

How are you influenced by Venice?

The audience here is very international, so I was trying to think about how to interpret nationhood in the history of the Biennale. Many Native people identify with our own nations; for instance, I’m a member of the Choctaw Nation of Mississippi. It’s about breaking out of the umbrella terms of indigenous or Native American and moving into specificity. We have so many tribes represented here during the run of the exhibition. Most of the materials and the aesthetics I used are drawn from 20th century intertribal aesthetics, a period defined by bringing people back together and forming a new kind of vision.

A vision for community. On why the artist cladded the U.S. pavilion in bright red swatches, referencing the Missing and Murdered Indigenous People Crisis, Gibson shares: “The late 1930s, when the U.S. Pavilion was built, was a very traumatic time for a lot of Native people, from urban relocation to extreme poverty and boarding schools…” Interrupted by a visitor who climbed atop Gibson’s amalgamated pedestal sculpture to pose for a photo, — a white man climbed atop an artwork intended as a monument for people historically ignored, and fell off — Gibson expresses care and concern while remaining poised. “He’s okay.” As he returns to the conversation, he speaks with vigor: “I just wanted to renovate the building. I didn’t want to erase it — I just wanted to renovate it.”

Photography by Joshua Woods for PIN–UP.

Installation view of Jeffrey Gibson’s the space in which to place me. From left to right: The Enforcer (2024); WE WANT TO BE FREE (2024); Mural: WE ARE MADE BY HISTORY (2024). Photo by Timothy Schenck.