Installation view: Isaiah Davis, Confessions of Fire, 2025. Photo by Darío Castillo for PIN–UP.

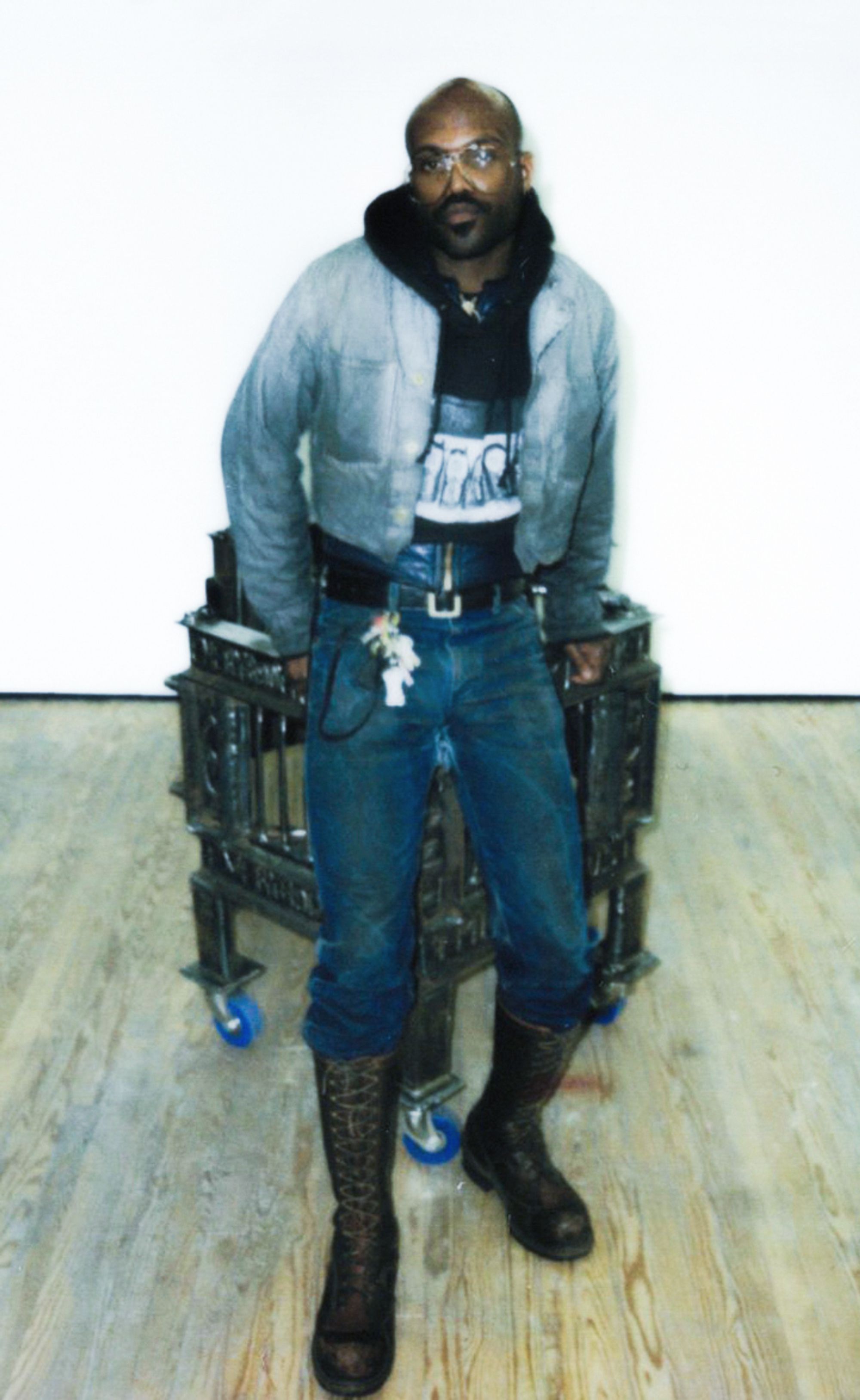

Portrait by Darío Castillo for PIN–UP.

Isaiah Davis’s solo exhibition, Confessions of Fire, is about many things: music, film, slang, sex, class, and the image of the Black artist. But at its core, he says, “it’s a show about steel — about how the steel came to be.” You might also say it’s about how a boy comes to be a man. The works staged at King’s Leap on Henry Street (mostly sculptures, free-standing or wall-mounted, plus four painted signs) reference the artist’s youth pop culture superheroes: Cam’ron, whose 1988 debut inspired the show’s title, and Prince, Michael Jackson, James Brown, Ving Rhames, among others.

Davis discovered the exhibition’s namesake — Cam’ron’s Confessions of Fire — as a six-year-old growing up in the Bronx. He pictured a future self that looked like its cover art, dressed in leather overalls, swinging around a big hammer at a mill somewhere. A version of that vision has been realized at King’s Leap. Although this work foregrounds steel, leather is Davis’s most consistent medium. It’s featured in his video work, in the form of costume, and comprises early sculptures like 2021’s White American Flag. The artist wore leather by necessity as he forged, embossed, and Frankensteined the works in Confessions of Fire. They take the forms of cages, safes, or machines (Remy); padlocks and chains (Gay Secrets); sometimes a phallus, others a hole (Paul and Michael).

Davis’s practice demonstrates how these materials — which he once understood as “hard,” literally and figuratively — are most susceptible to damage at their softest. The more rigid self-belief, it follows, the easier and more disastrously it’ll shatter, especially in the masculine context. Davis looked up to Ving Rhames (best-known as Marsellus Wallace in 1994’s Pulp Fiction) not because he played a gangster, but because of the confidence it took to act a part in which that gangster is sexually assaulted. In 2000, Rhames, a straight man, would go on to play a drag queen in Holiday Heart.

Installation view: Isaiah Davis, Confessions of Fire, 2025. Photo by Darío Castillo for PIN–UP.

Isaiah Davis, Remy, 2025; steel, aluminum, canvas, oil paint, wood. 39.75 x 44 x 33 in.

Cam’ron’s gender-charged self-styling also shapes Davis’s work. Once the rapper wrested a bit of control from his label in 2002, he started wearing the all-pink fits he’s famous for — “an almost camp reassertion” of straight masculinity, Davis writes, in that he wanted to show he was man enough to claim something feminine. Around that time, the rapper popularized pause, East Harlem slang in the vein of no homo. It’s invoked to stop an interaction and linger on the moment an offender said or did something gay. “[Pause is] an opportunity and occasion for straight men to laugh at [heteronormative] rigidity, even as they are bound by it,” Davis goes on — and, in practice, a chance for a collective fantasy of said gayness, among bros. (No homo!) The artist’s work often comes back to this: The policing of queerness, of outsider-ness in general, is what makes it ever-present and an object of obsession.

Confessions of Fire is Davis’s visual exploration of pause, as a linguistic container — the sculptures’ cavities, existent only thanks to their metal, protect or obscure secrets or treasures. Whatever the viewer fills it with is what it becomes.

Isaiah Davis, Slave, 2025; steel. 35 x 21 x 28 in. Image courtesy of the artist and King's Leap. Photo by Stephen Faught.

Isaiah Davis, Slave, 2025; steel. 35 x 21 x 28 in. Image courtesy of the artist and King's Leap. Photo by Stephen Faught.

Morgan Becker: As a kid, why do you think that Cam’ron album cover so captured your attention? Was that kind of imagery out of the ordinary?

Isaiah Davis: This was the late 90s. It was becoming a more computer-centric society. There was this idea of the android — of human beings merging with machinery. And being from New York, an industrial kind of city, that idea’s always been there. What had the most effect on me growing up was Terminator 2. Shaquille O’Neal had a movie called Steel with very similar imagery. It was a cultural narrative: You know, steel, Blackness, fire. Even if you look back to slavery. Cam’ron has a verse where he says: “Back in the days, we was slaves, whips and chains.” He says, “It’s tradition. All I got? Whips and chains. / All I did? Flip some cane.” It’s about oppression, confinement, all that stuff. It’s a part of the Black narrative.

The most prominent works, on that note, look like cages. They’re also creature-like, I’d say more than the sculptures that evoke the human body. Do you understand them as functional — tools to contain and protect? Or as beings with some kind of agency?

If you make a tool, the intensity of the tool has to match the intensity of whatever thing it’s doing. A hammer is a blunt instrument; it looks like a blunt instrument. The tools to get to freedom probably look a lot like confinement — they’ll have the same intensity as confinement.

The form follows the function.

Exactly. I don’t think about them as industrial. That’s just the environment they came from — like the shop gave birth to them. They feel like little companions.

Portrait by Darío Castillo for PIN–UP.

Isaiah Davis, Quick, 2025; steel, aluminum. 39 x 41 x 31 in. Photo by Darío Castillo for PIN–UP.

Portrait by Darío Castillo for PIN–UP.

I thought of them as industrial because you mentioned the importance of class to Confessions of Fire; I assumed you meant steel and leather representing the working class.

It’s more about communication. People who have money communicate to each other differently than the middle and lower class. The language I’m speaking is like slick talk. It’s slang. And a lot of slang comes from the so-called “lower parts” of society. It’s tied into it, down to the materials. But I’m not choosing things like drywall. It’s the guts — the infrastructure, made to last, made to house multiple stories. Actual stories, but height-wise too.

The height thing is interesting. When we were looking at Gay Secrets, you said that piece makes you feel like a giant.

But you know what’s funny? I don’t see any of those sculptures as big or small. They’re all medium-size. You know what I think the perfect height is?

5’7”?

5’11” is the perfect height! It’s medium, even though it’s not the average. It’s fairly tall but not too tall, where you have knee problems. If you’re too short, that has its own problems, like osteoporosis.

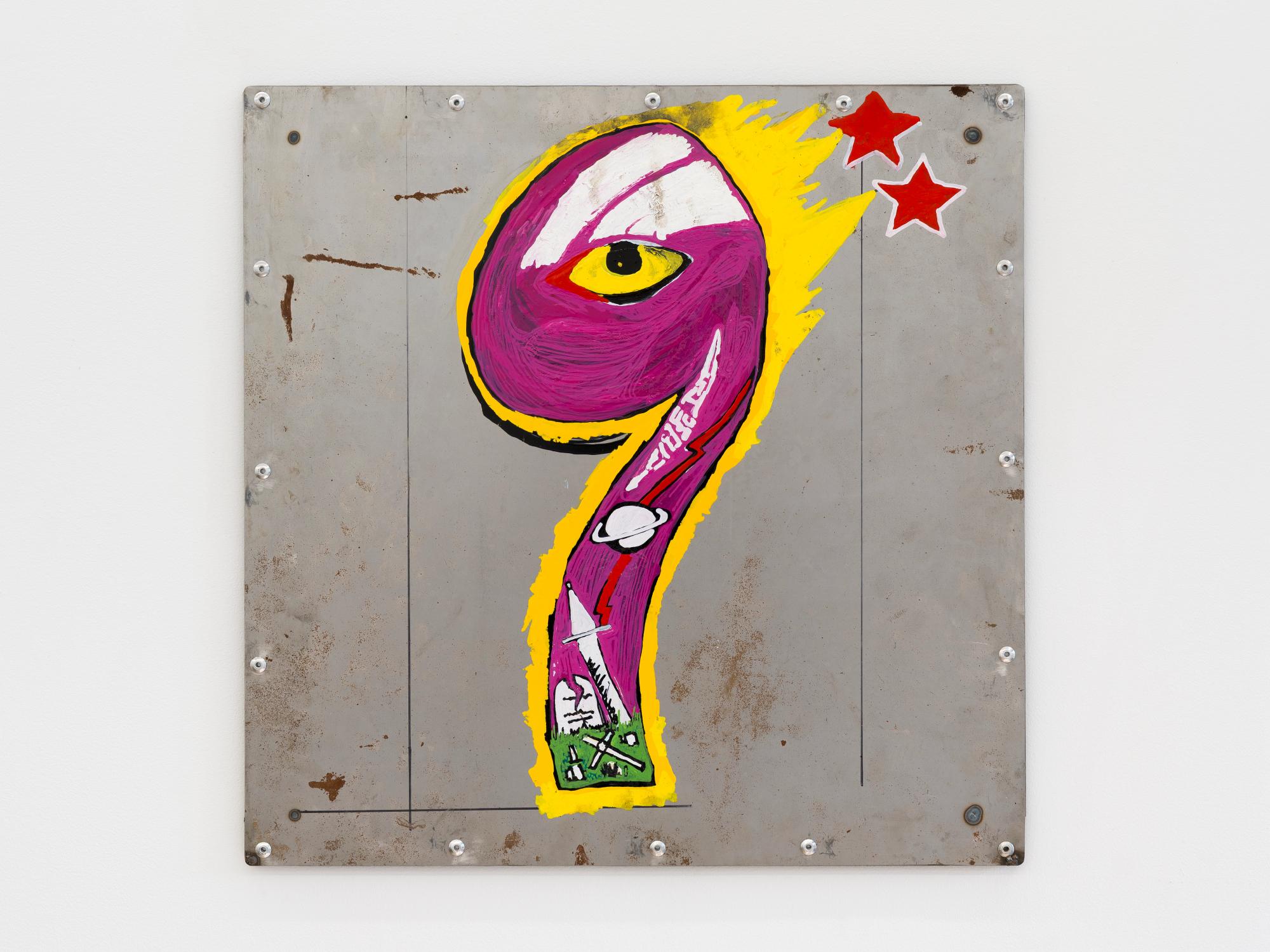

Isaiah Davis, 1999, 2025; steel, enamel, aluminum. 24 x 24 x 0.5 in. Image courtesy of the artist and King's Leap. Photo by Stephen Faught.

Isaiah Davis, 1999, 2025; steel, enamel, aluminum. 24 x 24 x 0.5 in. Image courtesy of the artist and King's Leap. Photo by Stephen Faught.

Isaiah Davis, 1999, 2025; steel, enamel, aluminum. 24 x 24 x 0.5 in. Image courtesy of the artist and King's Leap. Photo by Stephen Faught.

Isaiah Davis, 1999, 2025; steel, enamel, aluminum. 24 x 24 x 0.5 in. Image courtesy of the artist and King's Leap. Photo by Stephen Faught.

So where did you source the show’s materials? Do you envision the final product in your head, or work with what you find?

A little bit of both. Some of it came from the infrastructure of this building that was deconstructed. It’s from Pennsylvania — Bethlehem and Pittsburgh. Not even steel people would know exactly where it originated, but this is legacy steel. Everything you see here was in a straight line at one point. Raw material, I-beams. The embossing you see on construction sites. Iron workers would weld a company name or something into the steel. It’s very bodily, like scarification. It tells you who was here; the iron workers leaving a message for the electricians. So I’m leaving a message to somebody — another artist — [passing along] the source material.

On the scarification note, they do read anatomical. The chambers remind me of a heart.

Yeah, they’re access points — even if you can’t get inside of them, it suggests that you can. Sometimes I put locks on their doors. Sometimes I leave them the way they are. I’m invoking the feeling of passing-through.

With the steel, it’s a way for you to reckon with rigidity… Do you see leather as its opposite, in that it can read so differently from context to context?

No. They’re not one in the same, but they’re complementary. Chocolate and peanut butter. Everything about leather — the queer aspect of it, the working aspect, the outsider aspect, the outlaw aspect — I feel deeply. It is “me.” You know that expression, the clothes don’t make the man? I feel it that way about leather: You make it into what it is. That empty space that happens in my sculptures — what you fill it with, with your mind, is what the sculptures become.

Isaiah Davis, A Series of Sad, Satanic Contracts, 2025; steel. 19 x 17.5 x 3.25 in. Image courtesy of the artist and King's Leap. Photo by Stephen Faught.

Does steel have the same level of nuance for you?

Absolutely. Because in order for it to be malleable, it has to become soft. Then it becomes hard. Visually it’s impenetrable, but it can be penetrated. It kind of wants to be penetrated so it can kind of move on.

In both Confessions of Fire and your first solo show in 2021, I HAVE NO MOUTH AND I MUST 333SCREAM at Participant Inc., you draw a connection between the economic exploitation of Black people and their literal consumption — and how all that plays into the modern image of the Black artist. Back then, though, you took a much heavier approach, leaning into cannibalism, the horror genre. The tone of Confessions of Fire is really kind of playful. How’d you get from there to here?

What the world needs is a kind of optimism, but not no bullshit optimism. It’s almost like it’s important to live for what comes after this. Whoever we may be elders to in the future, they’re gonna need us! With my first show, I knew things were moving into a dark space. If I’m being honest with you, the pandemic was one of the best times of my life. I had peace and quiet, and then everything with the George Floyd protests… It just seemed like we as a country were banding together. It’s like we said, “Here it is: This is the goodness in the world that we have to offer.” And then everything flipped on itself. Right now I feel like the answer is not more darkness. In my first show, violence was there, but it wasn’t all about violence. I think that shit is corny. Because that’s not how your life was. There’s laughter inside of those moments. There’s joy. It’s up to you to show that.

Isaiah Davis, Paul and Michael, 2025; steel. 14 x 5.25 x 6 in. Image courtesy of the artist and King's Leap. Photo by Stephen Faught.

Isaiah Davis, Ving Rhames, 2025; steel. 23.25 x 4 x 6 in. Image courtesy of the artist and King's Leap. Photo by Stephen Faught.

Detail: Isaiah Davis, Ving Rhames, 2025; steel. 23.25 x 4 x 6 in. Image courtesy of the artist and King's Leap. Photo by Stephen Faught.

I was curious about something you wrote, about slang being “fugitive and improvisational.” What do you mean by fugitive?

Slang is of the moment. It can be clunky, but most of the time it’s geared towards efficiency in speech. If you get it, you get it. If you don’t, you don’t. And in order for you to get it, you got to be around the people who speak it. I hear young guys from the same neighborhoods I’m from saying all sorts of stuff I don’t know. I don’t know what the fuck they’re talking about! Slang is fugitive because it doesn’t want to be caught. The moment you catch it, you have something up on them. You have the money. You have the status. [They might be] beating you in every single other thing, but you beat them in communication. That’s one thing that they say: I got that over you. “You don’t even know what this is. I make the culture.” Me saying it’s improvisational—that’s because it’s really based off of where you’re at. Anybody can come up with slang. There’s Waspy slang out there, and if you say it with confidence, that shit is kind of cool.

Like what?

Like when they say, Pow! Or, You’re skating on thin ice! Shit like that is tight.

Portrait by Darío Castillo for PIN–UP.

I wanted to ask about Pope.L’s Hole Theory, which you reread as you developed the show. How did that text lead to your “theory of pause” — in which, essentially, the word as it’s used to assert an absence of gayness actually makes that gayness ever-present?

Hole theory is this idea that infinite possibilities exist where there appears to be nothing. [The phrase] no homo has existed for years, but pause is more popular recently. It’s in the social lexicon. I’m thinking about it almost in a Fluxus kind of way, where it’s like: If you were supposed to interpret pause, how would you? What does a literal pause mean in a conversation? To me, pause is like a void. Somebody says, Oh, damn. He got a big old head. Pause, right? And it’s like, Are you telling me to think about a big penis tip? Is that what that means? It is! But then it’s also: Pause and reflect on the fact that you just said something gay, and now we’re gonna laugh at you, because we’re so straight. This is the paradox of heterosexuality: We’re so straight that we’re gonna wear these tight spandex uniforms, smack each other on the butt, and take showers naked. Or even the paradox of group sex, where it’s one woman and four other guys. It’s like, Yeah, this is straight! It is because it’s reinforcing these roles of power, where the men are on top and the women are down here. But it’s the gayest thing! It’s incredibly gay. So pause is mad gay, because you’re telling me to reflect on homosexuality. It’s also like, we should just be working the fuck together — because heterosexuality needs homosexuality to exist.

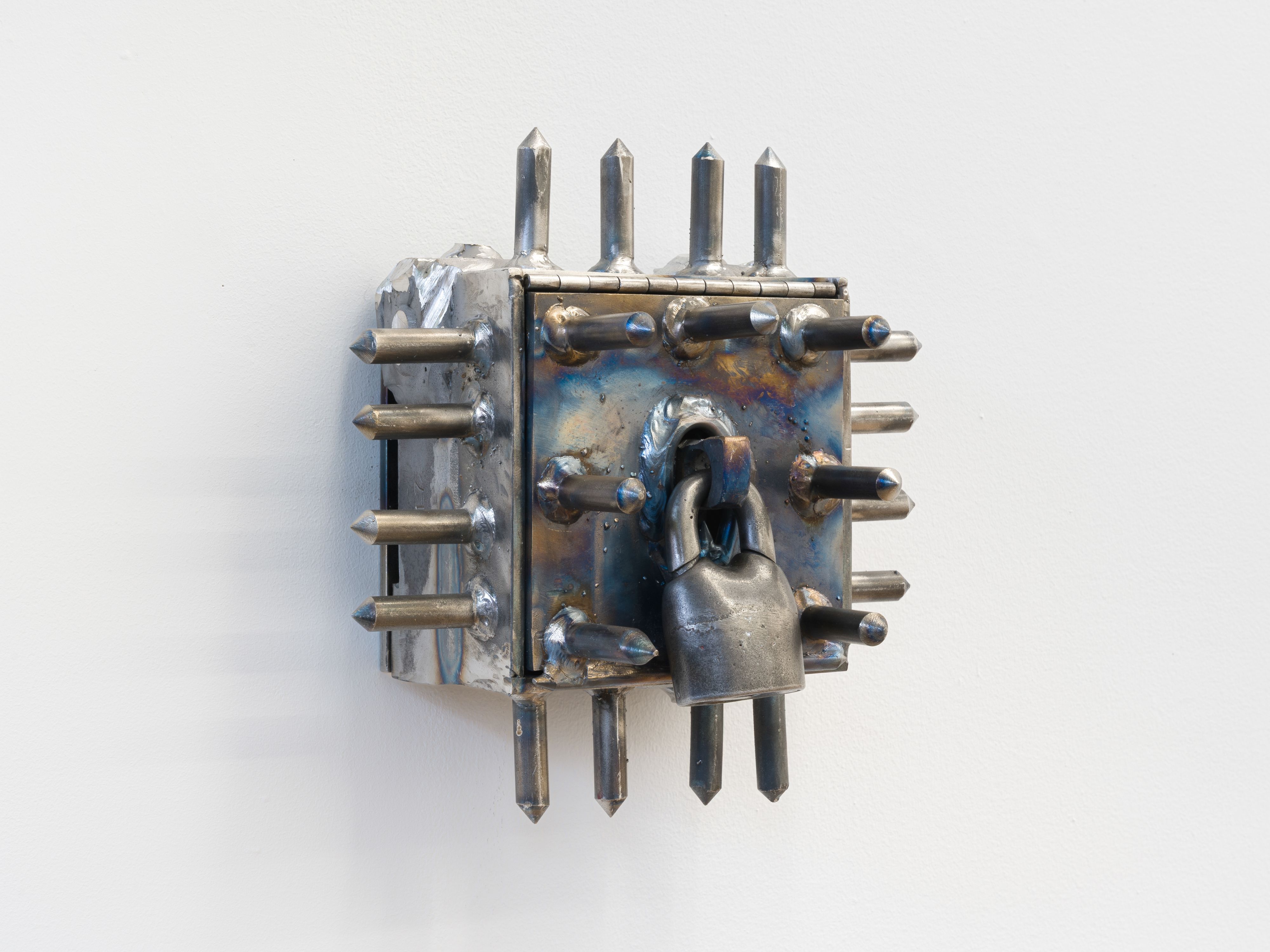

You mentioned Gay Secrets was the last piece you made. What about it got the show to feel complete?

It was the period to the show — this box of things you don’t want people to know about. It’s heavy-duty, spiky, like defensive architecture. Societally, there’s always this stigma that comes with deviating from anything heteronormative. I thought about it as a giant because what creates the secret is something that you feel like is bigger than you. But it’s also special to have a gay secret. There’s something precious about that.

Isaiah Davis, Gay Secrets, 2025; steel and human hair. 10.5 x 10.5 x 6.5 in. Image courtesy of the artist and King's Leap. Photo by Stephen Faught.