Andy Harman’s Brooklyn studio, photographed by Roe Ethridge for PIN–UP.

The artist Andy Harman in his Brooklyn studio, photographed by Roe Ethridge for PIN–UP.

Leave this like that over there, the title of Andy Harman’s recent solo show at L.A.’s Lauren Powell Projects, is an apt instruction for an exhibition that recreates in part the artist’s Brooklyn studio. Not only does it hint at the precise chaos of a sculptor’s workplace, it embodies the deft, lightly-worn authority the Ohio native wields as he twists and molds mundane materials into vibrant new shapes. Like that, indeed, because nothing is left to chance in Harman’s universe: every object — giant velvet scrunchies, bits of vinyl, pillowy cereals, huge shiny Cheeto sticks, stripper’s fringe, ceramic donuts, paper towels, a single sneaker — is placed exactly where it should be. Rather than symbols, these objects are tools to create form and to shape space, just the same way Richard Serra uses CorTen steel. Despite his institutional bona fides, Harman works in defiance of the art world’s elitist aura: you won’t find him performing blue-collar drag for wealthy collectors or serving the art-world trope of “elevating” mundane objects to the rarified order of sculpture. His embrace of the shallow depths of American consumer culture is free of cynicism, but not of humor, throwing into question value in both the art and the real worlds. This conceptual gray zone may in part owed to Harman’s longtime job as an art director and set designer, working behind the scenes of some of the most recognizable fashion campaigns of the past 15 years. For PIN–UP, the 54-year-old recounts his trajectory, from Ohio punk to Vegas janitor, from Yale MFA to set design — and hints at what’s coming next.

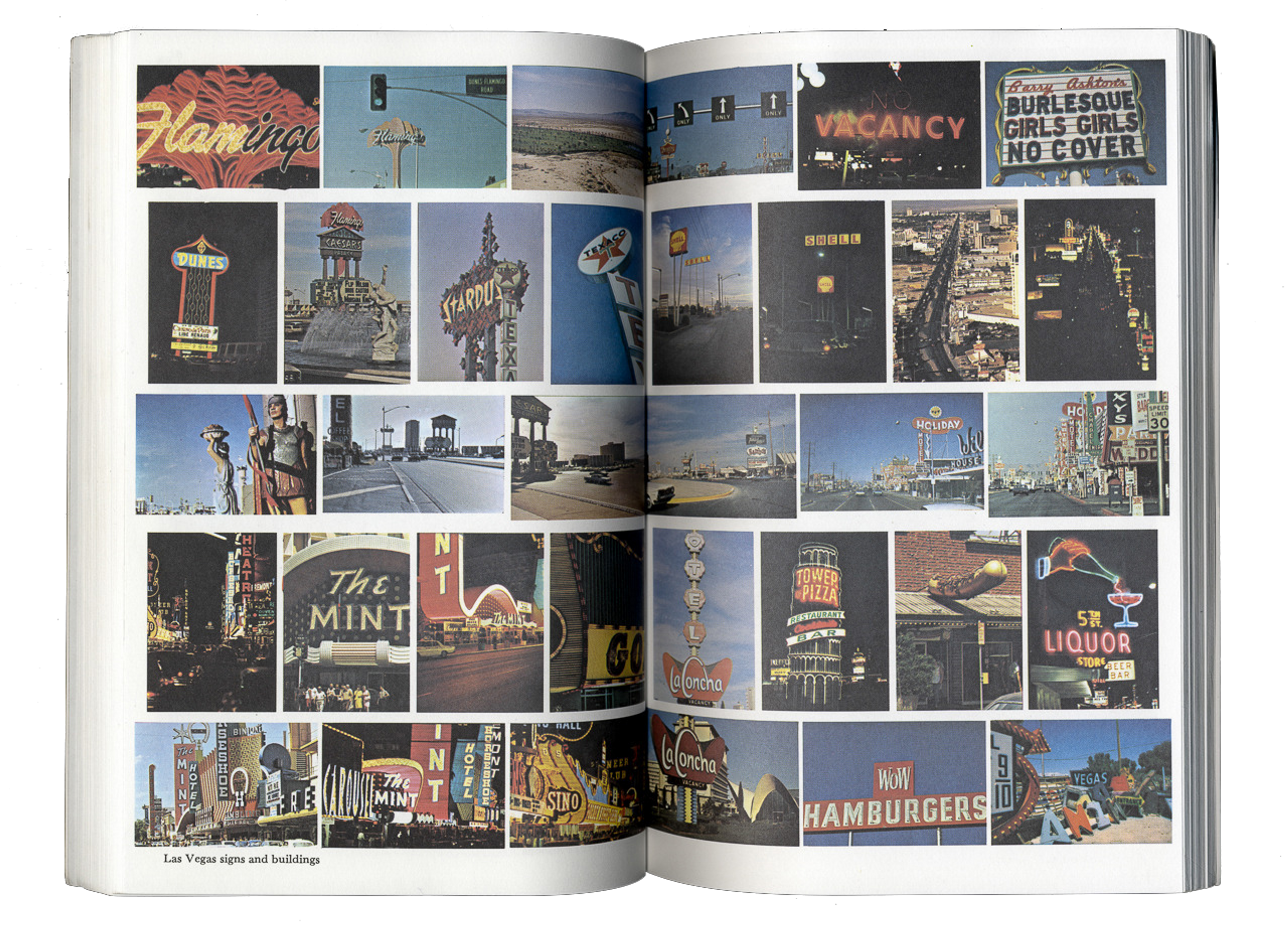

Double page spread from the 1972 book Learning from Las Vegas by Denise Scott Brown and Robert Venturi.

Felix Burrichter: How did you come to sculpture?

Andy Harman: I don’t know exactly how that happened. I was in my last undergrad year at Kent State, Ohio, and I switched my major. Something hit me. I was doing all these crazy inflatables with garbage bags and patterning — I graduated with a BFA in sculpture based on only six or seven months of doing it. I’d just read this book, Learning from Las Vegas [by Denise Scott Brown and Robert Venturi]. So on graduating I drove to Nevada and worked as a janitor at a casino for a year.

You moved to Las Vegas because of Learning from Las Vegas?

Yes. I was obsessed with it. I love it so much. It changed my life. It informed so much of what I was trying to get at. It was a true indicator of an American culture that really is its own thing. And I was like, “Well, I don’t want to move to New York and be an artist, that seems really boring. Like, who cares?” I was really a punk kind of kid. I came from a blue-collar family and New York just seemed whatever. Once I got to Vegas, I literally lived on bricks of cheddar, bean sprouts, and ramen noodles. That’s all I could afford. It sucked. I couldn’t really drink. Couldn’t do anything. I was just there, but I loved it. It was so much fun.

Vegas in the early 90s must have been so different.

Yeah. It was before they blew up the Dunes hotel and casino — that happened right before I left. At the time I was really obsessed with Americana, and Las Vegas was the barometer for everything — the idealism of what it meant to live in America and grow up American. It was the mirror of everything I knew, but more extreme. And to see it on display in this way was really interesting. Of course they were fucking with it and manipulating it, architecturally and environmentally, which I thought was cool, though I have a different view now. But going west to me at the time was an optimistic venture — I was going to the idea of a new life. You know, the West has always been a symbol of a different life.

Andy Harman’s Brooklyn studio, photographed by Roe Ethridge for PIN–UP.

Andy Harman’s Brooklyn studio, photographed by Roe Ethridge for PIN–UP.

And then you returned to school, this time at Yale. How did you end up on the East Coast again?

I got into UCLA, ArtCenter, and CalArts. I thought I’d be going to UCLA because people I really loved taught there, like Charles Ray and Nancy Rubins. I went for a tour, but there was nobody around, no students. And I thought to myself, “Oh my God, it took me seven years to get through undergrad because there was no one checking on me. I can’t keep doing that.” I knew Yale was going to be harder. And it was hard. It was also well-versed in cultural theory because it was the 90s and that’s all anyone talked about.

Who was teaching there at the time?

Ronald Jones, John Newman, Robert Gober, who was a visiting professor. We picked our own faculty, and I think we voted on Felix Gonzalez-Torres, but he got really sick right before he was supposed to come. I was devastated by that. We also had Richard Serra, who was a fucking barn burner, honestly. He was incredible. He was actually a big influence for me because he was so interested in my story. He loved the Vegas thing. He also loved that when I got to Yale, I lost 75 pounds and came out of the closet. I was thinner at Yale than I was in eighth grade. It was partly because of anxiety but also because I started realizing that this is life — it’s happening. I need to stop drinking so much and focus. Because these people were going to eat me alive. They were a fairly carnivorous bunch at Yale.

Once you graduated from Yale, you moved to New York. I heard you were hired by set designer Marla Weinhoff, who had worked exclusively with Avedon.

Yes. She’s a legend. She did it all. She did the elephant picture. All the Versace. She did it for a long, long time. But she was part of this world that I just couldn’t get down with. They were like, “giiiirl” and “chichichi” and I’m like, “Oh, I am not there yet. I can’t.” [Laughs.] I worked with her a little bit before working with the boys from Yale again, but I didn’t like that either because it was too high-testosterone straight male. So I went to work for a carpentry shop that was all gay owned.

Close-up of one of Harman’s sculpture Boing (2020) made from posable pipe, velvet and rubber bands. Photographed by Roe Ethridge for PIN–UP

How did you even find that?

I don’t know, actually. I started working for Geoff Howell who was gay and had all these beautiful gay men who had rented offices in the bigger space. And then there was a carpentry shop, and I thought, “This is amazing. This is the gay world I’ve always read about and just knew nothing about.” They were older. They had lived through the AIDS crisis. They were aesthetes. They went to the shows, they did all that stuff.

What kind of shows?

Broadway shows. And the museums. They were fabulous. It was so interesting. I’d never been around any of that. These were fully liberated, well-moneyed, in-control gay men. I mean, I realize there were a lot of problems there, whatever, but it was exciting. I worked for them for a long time, doing interiors for showrooms like Coach. And then I started doing set design on my own.

Did you continue your art practice?

I continued for a while, on and off. I became really obsessed with readymades, like cigarette packaging — Marlboro and Camel, the desert. I was doing all this spray-paint and stencil work. And I was obsessed with “Why did the chicken cross the road?” What? So I made work based on the chicken crossing the road and smoking cigarettes. I threw a lot of stuff at it, different influences: art-history things, product design, all sorts. I do tend to gravitate towards things that are considered nothing, like a rubber band, a scrunchie, a refrigerator magnet, a drag queen’s feather boa.

The artist Andy Harman in his Brooklyn studio, photographed by Roe Ethridge for PIN–UP.

Do you separate your art from your commercial work? Or do they inform each other?

They totally inform each other. You know at Yale I was always labeled “the white-trash boy,” and I hated it. And I hate it when people call my work “kitsch.” I think kitsch is a treacherous word full of all sorts of cultural slander. It’s so elitist. What I learned working with photographers and directors like Roe Ethridge, Terry Richardson, and Danielle Levitt is to let myself go there. When I first started working with Roe, he wasn’t doing fashion stuff at all. I remember one day, early on, we were asked to do a still-life shoot in a house for AnOther Magazine. We had all these accessories and only two days to shoot them, so we were going nuts because we had to hurry. We did something like 40 pictures, and it was so frantic that anything went. The house had statues in the yard and I was putting the handbags over their heads. I clipped a 700,000-dollar brooch to a piece of lattice. We had mannequin legs and I was shoving them in the ground with the shoes. The second day was at a studio, and I was putting balloons in panty hose, wrapping belts around toilet paper, and we were both just like, “I can’t believe that just happened.” It was almost like we were fever dreaming. We realized we could get away with pushing against that wall of consumerism and fashion. That’s when I realized I should start pushing again in my own practice. I had enough money from working with Roe and Terry that I could afford a space. I had less inhibition and it all opened up a little bit — slowly at first — and got bigger and bigger.

That’s when you started producing your own pieces again?

Yes. I did giant macramé owls and leather cactuses — I did a limited edition of those, we sold ten. At that point I was like, “Well, I’m going to do sculpture, but I’m going to think of it in terms of commerce. And I’m going to think about it in terms of that 60s California idealism.” I especially loved the owl because I used a macramé kit, the sort of homemade spirituality you could buy at the store, which I thought was silly and amazing at the same time. It was optimistic. And then I did leather cheeseburgers, which were modular. You could order a triple patty and get cheese and lettuce and mayo. The cheese was Chanel quilting, the lettuce was a ruffle, the mayo was piping. I did different sizes. And I did them as totem poles — I was really obsessed with Ettore Sottsass at the time.

Even though they’re referencing these everyday phenomena, there’s so much refinement in the materiality. I mean, it’s a very elegant burger.

I’m not sure if elegant is the word I’d use. Like there’s a lushness to it… It was really just me saying, “Well, I’m going to make it really beautiful so that you can’t fight it with the old kitsch and camp number.” Because it’s not. Yes it’s well made, with really expensive fabrics, but they’re clashy and antagonistic and there’s sort of an ugliness. Although I’m mostly speaking about the scrunchies at this point.

How did the scrunchies start?

They started because I like rubber bands. And the lamp you see there is a giant twist tie. The material I used for that Twist Tie came about because I was tired of using leather, so I used vinyl, which I like a lot — I think it’s ingenious, especially Italian vinyl colors from the 50s and 60s, which were used as a result of post-war economics. Recently I did a vinyl scrunchie to try and figure out if I could work that material back in again. A scrunchie is like a baroque rubber band. For me, it’s an armature to plug a lot of stuff into. I like the physicality of rubber, and I like using it to hold stuff together. The scrunchie was sort of a decorative version, so I could bring up more trim, more fabric, and more textiles that I really like. I use that material to hold it to shape because I realized I don’t actually want to try to define what it’s holding together. When I’m doing the shape, it’s fully performative. It starts to feel like it’s got a character to it, a psyche of some sort. I like that interplay because it’s bringing the body back into it without doing anything that has a body in it. I could keep going and going…

Where do you source your fabrics? For example, this sparkly green one?

I got that at the stripper trim store in the garment district. I started adding the ping-pong balls as sort of fixed points, like bullet points. It’s not going to move again. It’s anti-heroic. I wanted to make it feel heroic as if it’s permanent, but I made it malleable. If you cut the rubber band it falls apart. It’s a myth, it’s all a lie. This heroic masculinity is bullshit. We can build it up and we can make this grand sweeping gesture and make this statue. But it needs to fall apart. And so that’s where the malleability of the actual Cheetos or the scrunchies comes into play.

There’s still a lot of Vegas in this work.

I’ve been embracing Vegas recently.

The Cheetos seem very Vegas to me because they represent extreme artifice — I mean they’re the most artificial food.

Yes. But you see, the Cheetos have a very post-minimal aesthetic to them, and I would be mortified if you saw it as cynical, like I was making fun of formal sculpture. I’m speaking through it for sure, but I’m not making fun of it. That’s not what it’s meant to be. It’s just the vocabulary I’m using: the Cheetos and the scrunchies are a kind of agitated mark making that’s coming out of Cy Twombly. I don’t know that I understand it other than a total guttural relationship to it. Everything is so collapsed now in our information age, it’s all leveled. And the Cheeto is as much part of my language as anything in art history.

Now you’ve wrapped up the show at Lauren Powell Projects, what’s next on your agenda?

I’m looking forward to going back to the studio to make new work. I also just finished a book on my boa drawings, Right Back at You, which I worked on with the designer Riley Hooker. It was a great process. It’s a mix of my drawings with images from my studio — the interplay between the two is great. It’s more of an object, which I love — I can’t wait for everyone to see it!