Installation view, Julie Becker: I must create a Master Piece to pay the Rent, MoMA PS1, New York, 2019. Photo by Matthew Septimus.

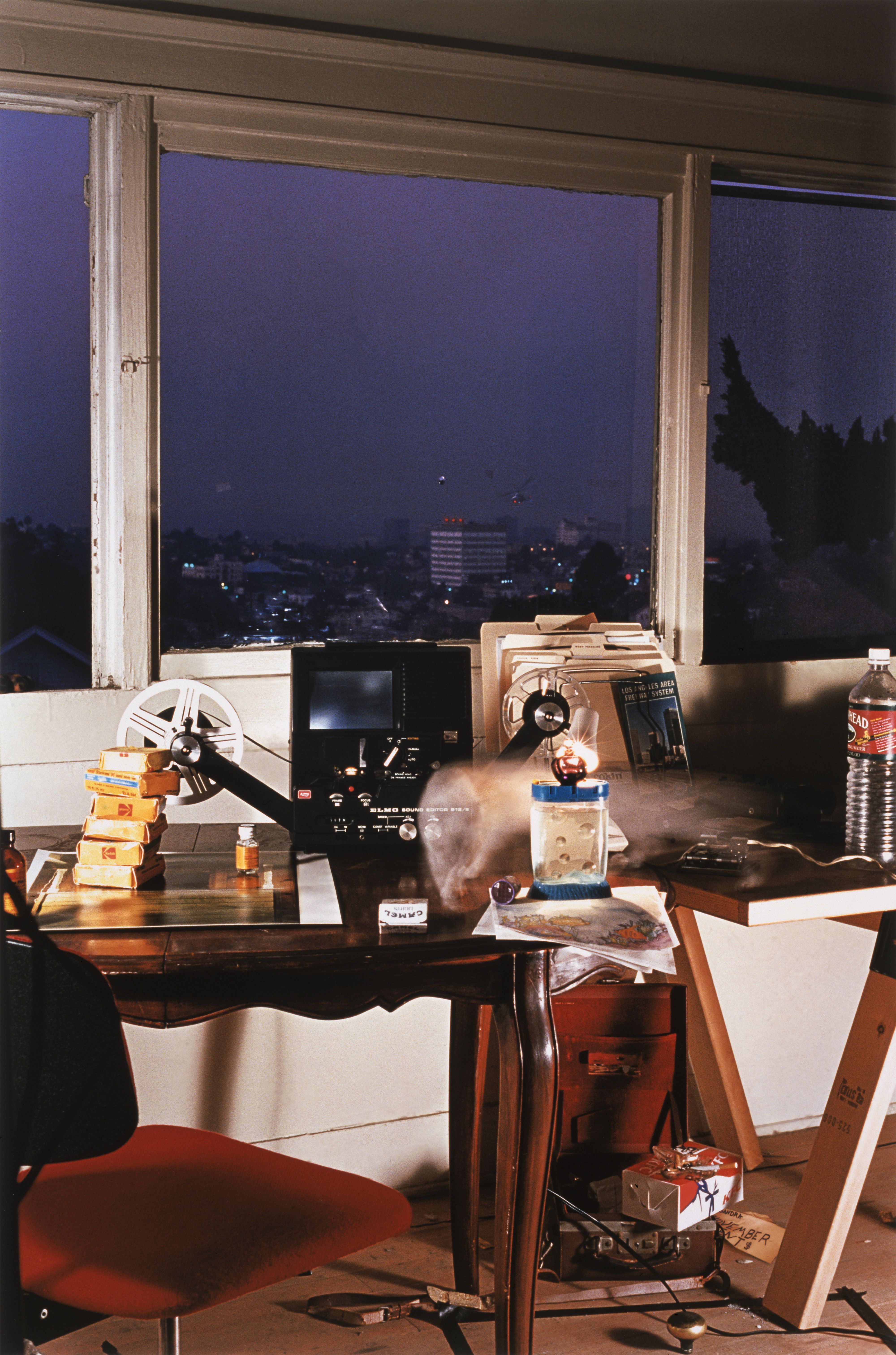

Researchers, Residents, A Place to Rest, 1993-1996. Mixed media installation. Photo by Matthew Septimus.

I’ve always struggled to keep a clean house. All the hyper-functionality I try so hard to project elsewhere in my life breaks down here, in the pile of clothes on the chair, the milk crates full of junk. It’s why I relate so much to artist Julie Becker’s domestic scenes, full of exposed cords and overflowing cabinet drawers. At the same time I see the thing I most want and yet feel so far away from achieving: an idiosyncratic emotional and psychological state channeled through a work of art, that enduring communication of self that can survive the demise of the physical body. I found Becker’s work only after she passed: born in Los Angeles in 1972, the artist lived there until she died in 2016.

I must create a Master Piece to pay the Rent, Becker’s first museum survey, debuted in 2018 at London’s ICA before traveling to MoMA PS1, where I experienced the installation as a claustrophobic succession of corners and corridors, the interiors starting at a scale reminiscent of dollhouses and architectural models before transitioning to life-size rooms. When the ad-hoc clutter of transient abodes is translated into the 1:10 scale generally used to project aspiration, it’s gutting — the pallet bed made from a pint-sized folded blanket; the sleeping roll tied up on a Lilliputian office floor. There’s a tenderness in these signs of improvised living so meticulously rendered in miniature, the undeniable care that’s gone into recreating scenes defined by the ways society is callous, where a place to rest is no guarantee. And there’s also anxiety: the attention to detail reads as obsessive while the scale of the worldbuilding, room after room of the debris of lives unsettled, borders on the compulsive. The drive to chase something that’s forever out of grasp feels a part of this restlessness. In a 2002 text for one of Becker’s exhibitions, Chris Kraus wrote, “you’d been preparing this show called Whole for nearly four years, and you were starting to realize it would never be finished. It was becoming an endeavor … gorgeous and doomed.”

Whole (Projector), 1999. C-print on aluminum. Courtesy of Greene Naftali, New York.

Becker’s biography proves that instability was formative. She was the child of artist parents, constantly moving from one apartment to the next, a kid whose fantastical imagination seems to have gotten tangled up in her early experiences of a precarity that remained a constant. As burdened as her work is by the heaviness of housing injustice, it is also threaded through with childlike wonder — Becker’s models in their scaled-down size can’t help but feel like toys. Her drawings are decorated with glitter and her videos are made up of samples from Disney films and The Wizard of Oz. The title of her survey I must create a Master Piece to pay the Rent, which comes from a phrase in one of Becker’s drawings, suggests how the two elements feed into one another: imagination and interiority must be extracted into something commodifiable, the artistic masterpiece, to maintain shelter, safety, a roof overhead. And Becker’s work manifests psychic interiority in its representations of interior space, suggesting how interdependent the two are. Modern subjectivity is produced through décor as much as it is reflected in the furnishings: nesting doll vessels, mind, body, room.

There’s another story from Becker’s life often told to contextualize her work: the artist moved into a bungalow owned by the California Federal Bank and was offered reduced rent in exchange for clearing out the belongings of the previous tenant, who’d passed away from AIDS-related illnesses; Becker purportedly proceeded to incorporate these left-behind artifacts into her Whole series (of which the bank is also a recurring subject). This is also fantasy, as it turns out. But Becker’s fiction is not without some truth: any house purchased with a mortgage is technically owned by a bank, and the artist did use as material the clutter left behind by the former occupant, though it seems they had neither had AIDS nor passed. In a text for the recent Becker exhibition, (W)hole, which opened at Del Vaz Projects in February, marking the first presentation of the artist’s work in Los Angeles since 2009, writer Joel Kuennen comes to terms with Becker’s mythmaking: “America failed the many, many people devastated by the AIDS epidemic especially gay men and people of color. Julie tapped into a metanarrative.”

Installation view, Julie Becker: I must create a Master Piece to pay the Rent, MoMA PS1, New York, 2019. Photo by Matthew Septimus.

Installation view, Julie Becker: I must create a Master Piece to pay the Rent, MoMA PS1, New York, 2019. Photo: Matthew Septimus

America continues to fail us: housing is not a right; real estate is a financial asset; apartments sit empty; tent cities grow; bodies the economy deems surplus survive houseless, in conditions less than humane. These bleak realities make Becker’s work germane to the dystopian moment — the makeshift bed constructed out of a refrigerator box; the maquettes suggestive of single-room-occupancy hotels, for many the last stop before homelessness (both from the sprawling installation Researchers, Residents, A Place to Rest, 1993–96); and the video featuring a bank building replica being lowered into a hole, a hand-drawn sign reading “Going Down” (Federal Building With Music, 2002). Still it seems overly expedient to turn too forcefully into political commentary the traces of a life cut short (Becker’s death at 43 is understood through mental illness, addiction, and suicide). This urge to make sense, and to make use, are too much like capitalism’s extractions; but as much as they’re permeated by the specters of eviction and destitution, Becker’s transmissions have an aura of mystery, mournful yet bright. I wonder about a detail in the photo Whole (Bar) (1999), a wooden placard fixed to a salvaged tiki bar: “If you can keep your head in all this confusion, you just don’t understand the situation.” And then striving to know without abandon feels like not enough.