Harley Wertheimer at his gallery CASTLE in Hancock Park, Los Angeles. Photography by Adali Schell for PIN–UP.

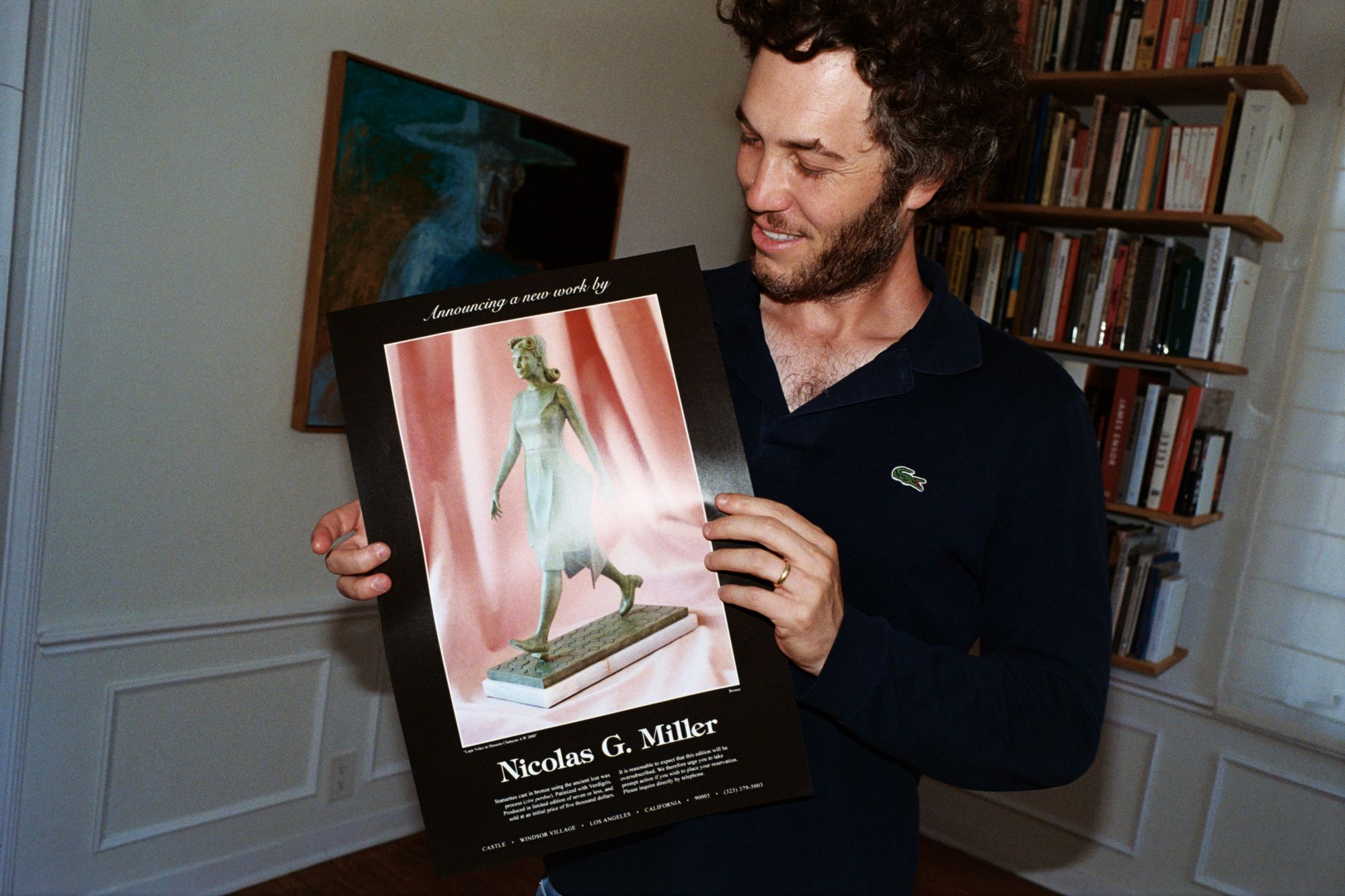

Harley Wertheimer poses with Jerry The Marble Faun, Chester, 2010. Photography by Adali Schell for PIN–UP

Harley Wertheimer has his hands in many pots, quietly creating spaces for people to convene around music, food, and art. As Vice President of A&R at Columbia Records, Wertheimer has expanded the reach of artists like Tyler, the Creator, The Internet, Vampire Weekend, and Haim. With Zelig, the Sony imprint he runs with longtime collaborators Mark Ronson and Brandon Creed, he helped kickstart the career of pop artists like King Princess. In 2022, he opened CASTLE, a gallery he runs from a historic Victorian building in Hancock Park, which continues a strong L.A. tradition of independent apartment spaces. CASTLE has exhibited rising artists from around the world, and architecture played a role in some of the shows — The 2023 exhibition The Disappearing City, used Frank Lloyd Wright’s treatise of the same name to explore utopian fallacies, architectural aspirations and suburban isolation through a mix of sculpture and painting. He’s also fulfilled his lifelong desire to open a restaurant with Stir Crazy, the longtime Melrose Avenue café he took over in the spring with co-owners Macklin Casnoff and Mackenzie Hoffman. In this interview the modern Los Angeles renaissance man charts the course of his career, from shepherding Amy Winehouse to the music studio in an old New York elevator to the parallels between A&R, running a small gallery, and the recent café venture.

Harley Wertheimer at his gallery CASTLE in Hancock Park, Los Angeles. Photography by Adali Schell for PIN–UP.

Harley Wertheimer pictured with producer Michael Uzowuru. Photography by Adali Schell for PIN–UP

Emmanuel Olunkwa: How did you get into music?

Harley Wertheimer: I spent my entire childhood in record stores, but I got my real start in music when I moved to New York in 2005. Within the first month or two of moving there, I saw Mark Ronson DJ at a house party. I approached him because I was a fan of his music and looking to help out, and he told me to come and interview at his studio on Mercer Street. That’s when I began interning for him and Rich Kleiman, who now manages Kevin Durant, at a label they had recently started called Allido. Between my classes at NYU, I was always at the studio. This was right at the time that Mark was hitting an inflection point in his career; a month after I started there, the Lily Allen project started, then Amy Winehouse, Adele, and Mark’s album Version. The studio on Mercer Street had a manual elevator, so I spent a lot of time shepherding all the artists up and down the shaft. I got to watch Mark become a successful producer, and I got to watch Rich become a successful music manager and businessman.

What happened after that?

I graduated from school and asked Rich for a job. We were really close at that point. He was one of the original executives at Roc Nation, where he was finding his footing, and I started helping him out where I could. He was working with Ronson, J. Cole, NO ID, and Wale. Mark was still hosting his radio show, “Authentic Shit,” every Friday on East Village Radio. EVR was an online radio station that broadcasted from the restaurant Lil’ Frankie’s, on First Avenue. The guys who worked at Lil Frankie’s had a show called “Southern Hospitality”; The Fader had a show. You could walk past Lil’ Frankie’s window and see Mark or J Scott DJing, and it became a community hang every Friday night. Mark was getting really busy and had started to trust me with finding interesting music that he should play on his show. I spent all week asking friends from other colleges for recommendations and combing blogs. That was my foray into becoming an A&R, which I didn’t really know was a job. It sounds ancient now, but we were premiering records and playing demos and I think it really had an impact. Mark told me one of the guys who had signed him to his record deal had just moved over to Columbia Records and was looking for young A&R people, and that’s how I ended up at Columbia, where I’ve been ever since.

Photography by Adali Schell for PIN–UP.

Harley Wertheimer pictured with Nicolas G. Miller's works. Front: Lupe Vélez in Hussein Chalayan A/W 2000, 2022; bronze; 16.25” x 4.5” x 10.5”. Back: Everett’s Relief (Quatrefoil), 2022; painted resin; 20” x 20” x 4”. Photography by Adali Schell for PIN–UP.

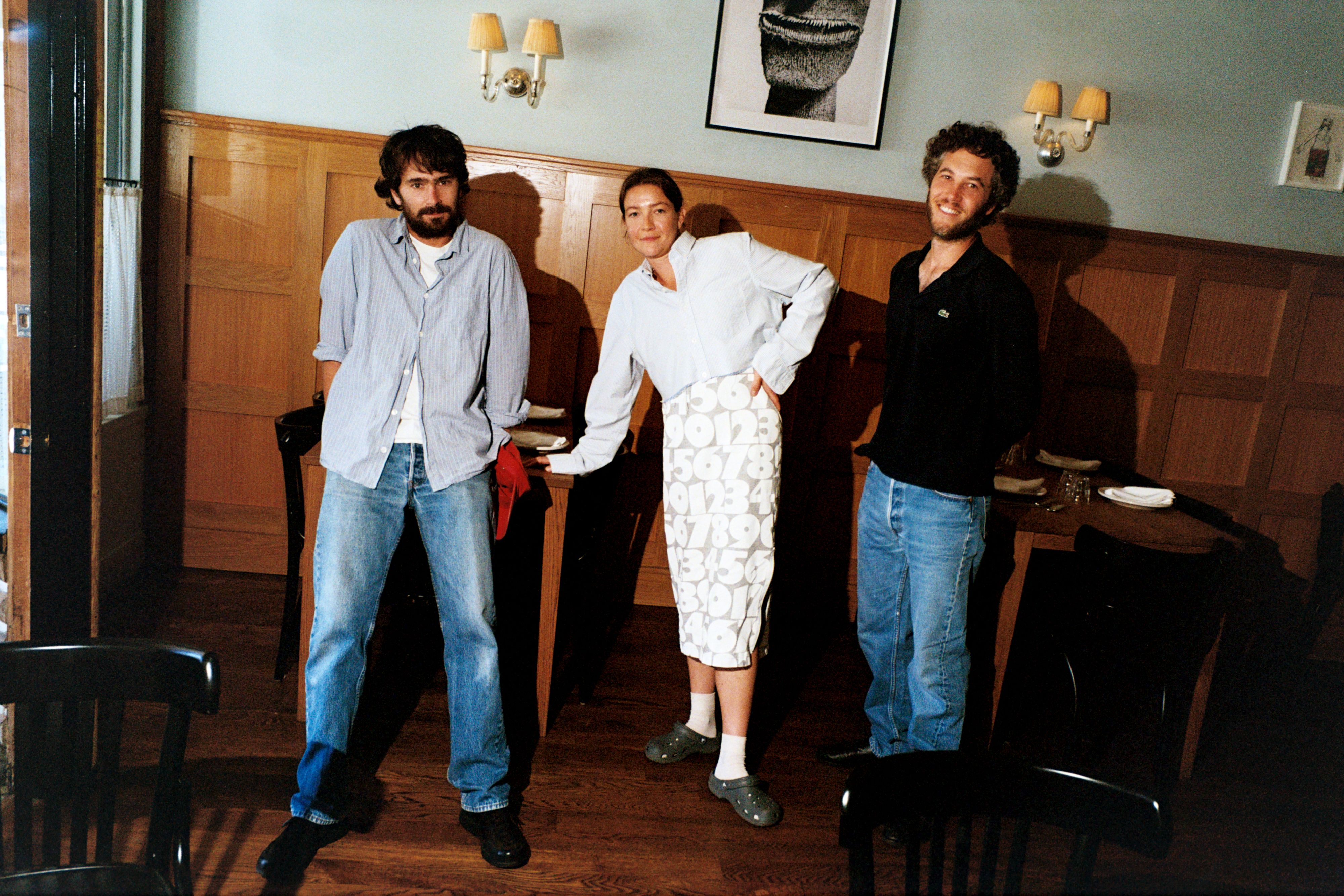

Harley Wertheimer with partners Macklin Casnoff (left) and Mackenzie Hoffman (right) at their restaurant Stir Crazy in Los Angeles. Photography by Adali Schell for PIN–UP

What does an A&R do? How did you get back to L.A.?

The day-to-day role has gone through different iterations, but at its core, the job is to discover and sign artists, convey their vision to the record label, and then put yourself at the center of their creative universe — whether that’s finding someone to mix their records, or a songwriter who can help them with writing, or simply handling their recording schedule. I spent a year working at Columbia in New York, but the artists that I started working with that I was most excited about were in L.A. When I saw what Tyler Okonma (Tyler, the Creator) and Odd Future were doing, I felt like I had walked into a Marvel film. Tyler, Earl Sweatshirt, Frank Ocean, MellowHype, Mike G, Syd Tha Kid, and Matt Martians — everyone had such an incredible point of view and such a dialed sense of self and their own persona. It was like discovering ten of your favorite new artists at the same time.

When did you and Mark start working together again?

I hadn’t worked directly with or for Mark since I started at Columbia. But we stayed very close and when he’d come to town, we’d always check in musically. I was always sending him stuff because he would build his albums with a cast. I moved to L.A. because the city was really having a musical resurgence at the time. A lot of studios in New York were closing down, and people started needing less of a traditional format for recording. People were moving to L.A., buying a house, and building a studio in their garage. Mark is signed to RCA, and I work at Columbia Records, both Sony labels. We thought it would be sick to find a traditional studio space and have that be one of the selling points for the new label we started with Brandon Creed. We wanted it to be a hang. We got the A-side of The Sound Factory, which is an iconic studio in Los Angeles.

Harley Wertheimer pictured with Jerry The Marble Faun, Latern, 2016. by Adali Schell for PIN–UP

What did you call it and why?

We called it Zelig, which means blessed, but it’s also come to mean somebody who is surprisingly ubiquitous. We’ve traditionally been drawn to people who cross a lot of sectors and genres so the name makes sense. I work with artists ranging from The Internet to Vampire Weekend; Brandon works with Troye Sivan, Charli XCX, Orville Peck. Our first artist was King Princess. I was in awe of her voice and her point of view. I just felt this personal connection to my partners and the artists in a way that I hadn’t before. It felt like there was nowhere to hide, which helped me take responsibility for myself, become more accountable, and grow up. Some people get closer to artists and find out they actually want more distance. I wanted to be closer than ever and had been yearning to have a physical space to invite people to. I was always trying to rally people to meet me somewhere, and this was the first time that I was able to say, “meet me at our studio.” I would essentially invite people over to make them coffee and we’d hang out. We were a block away from Amoeba so Mark was always bringing stacks of records back. We had this really nice intergenerational hang where younger and older artists and producers would comingle. During the pandemic, the studio closed and Mark moved back to New York, which was an emotional blow for me.

Harley Wertheimer pictured in the studio with producer Michael Uzowuru in North Hollywood, California. Photography by Adali Schell for PIN–UP.

This figures into how you decided to open your gallery space CASTLE.

I’d been collecting art for a while and had toyed with the idea of doing some shows in the studio space because there was this funny wood-paneled room where I’d constantly rotate the art on the walls. I was looking around for spaces and learning about the overhead costs, and, taking a cue from L.A.’s long tradition of home galleries, I decided to start one in my apartment. I was scared because I didn’t grow up in the art world and don’t have an art history background, but I had been collecting a lot of work and spent a good amount of time at galleries and with people who worked in art. I went to Parker Gallery, Nonaka-Hill, Chris Sharp Gallery, South Willard, and learned from my friend Ryan McKenna, who worked at Tilton Gallery. In the same way that I’m drawn to helping artists share their music, I wasn’t quite satisfied with just collecting artwork — I wanted to get into a position where I could show it to people. Having a friend over and showing them this new painting doesn’t feel quite as exciting as hosting an exhibition, figuring out how to hang the work, putting a check list together, and finding someone to write the press release. I like that process. At the core, as an A&R person or as a gallerist, you’re just trying to get as close as you can to the art making process so that you can do your best to bring it to more people and help support the artists. Your creativity lies in helping them expand their creativity.

Harley Wertheimer with partners Macklin Casnoff and Mackenzie Hoffman at their restaurant Stir Crazy in Los Angeles. Photography by Adali Schell for PIN–UP.

Harley Wertheimer holding an ‘advertisement’ for Nicolas G. Miller's sculpture Lupe Vélez in Hussein Chalayan A/W 2000, 2022. Photography by Adali Schell for PIN–UP.

Harley Wertheimer pictured in the studio with producer Michael Uzowuru photographed by Adali Schell for PIN–UP.

Harley Wertheimer with partners Macklin Casnoff and Mackenzie Hoffman at their restaurant Stir Crazy in Los Angeles. Photography by Adali Schell for PIN–UP.

Harley Wertheimer posed with Jerry The Marble Faun, Chester, 2010. Limestone with moss on dumbbell base. 15” x 14” x 17”. Photography by Adali Schell for PIN–UP.

What made you decide to open a café?

Opening a café had always been a dream of mine. I remember walking into a café when I was twelve years old and thinking, it would be sick to control the music in here. When we had openings for the gallery, I would get a café cart. For me, Los Angeles is a place that always has room for something new or fresh. I was spending a lot of time on this stretch of Melrose where there are art galleries and design shops like The Window, Seventh House, Hostler Burrows, Galerie Half, Object, and Maison d’Art. I approached the owner of the original Stir Crazy Coffee Shop during the pandemic because it had been closed for a while. I left notes asking if he was getting rid of the space, and he said yes. It reminded me of when we were looking for a studio space for Zelig. I was originally proposing houses and industrial spaces, but Mark said: “We need to find a place with an actual soul, a place that has hits already.” You want to work in a place that already has the spirits and the souls of the hit records and incredible sessions and incredible people that were there. Sound Factory has a long history of that. The Jackson Five recorded there, David Axelrod worked there, The Blackbyrds worked there, and Linda Ronstadt. The amount of people that tell me, “Man, I was writing scripts in here.” Or, “Man, in high school, I used to sneak out and smoke cigarettes there.” That’s the vibe you want for a café.