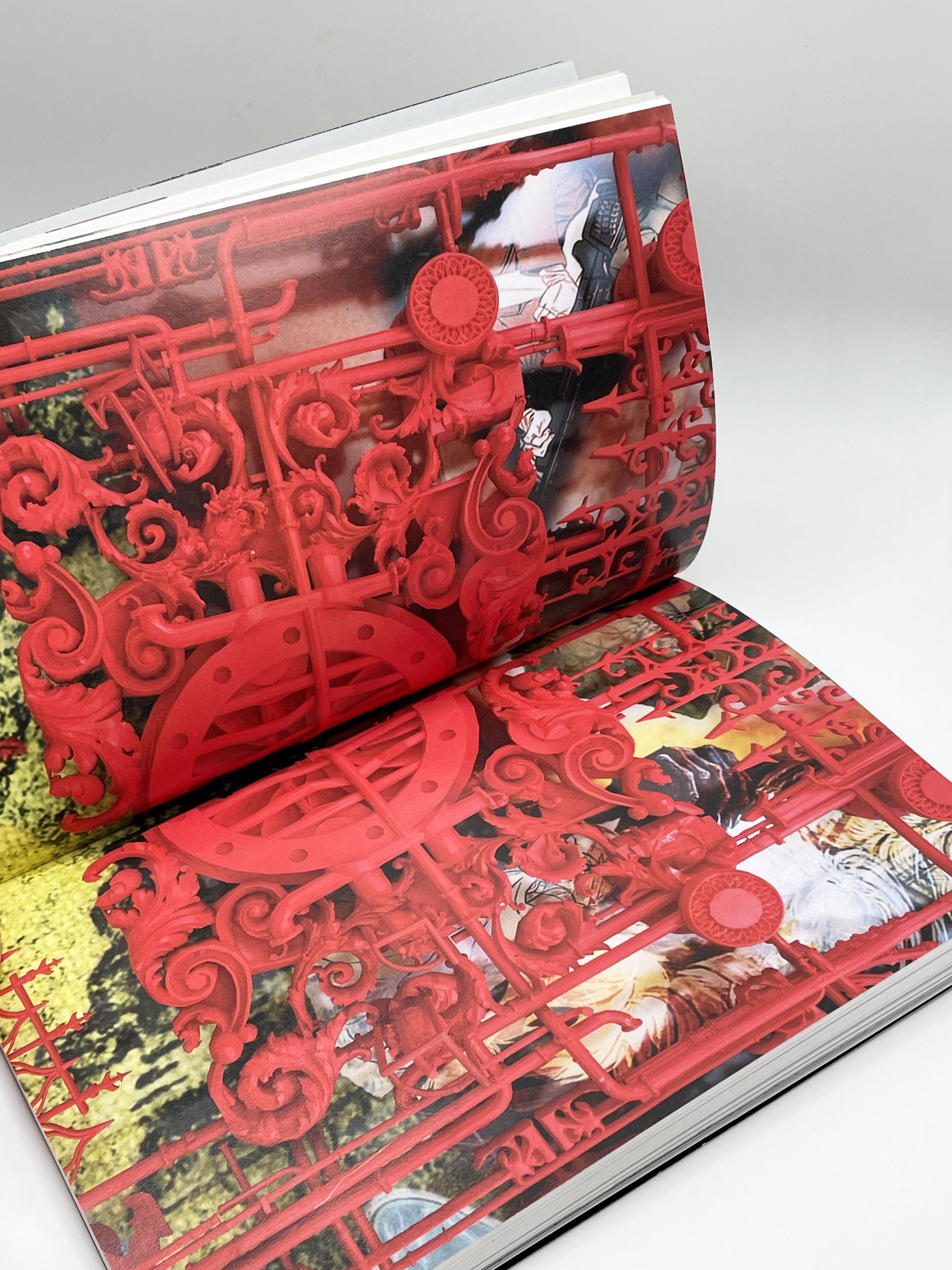

A spread from Genevieve Goffman’s The Triumph of a Lonely Place. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Portrait of Genevieve Goffman by Jeannie Sui Wonders for PIN–UP.

By design, I’ve encountered the artist Genevieve Goffman in fantastical spaces in Midtown Manhattan. The first time we met up was at the John Portman-designed Marriott Marquis hotel in Times Square. Sitting in the Broadway Lounge, flanked by jumbo TV screens playing a women’s poker tournament and the view of the blaring video billboard ads from the floor-to-ceiling windows, we talked about my contribution to her first book The Triumph of a Lonely Place. The focal point of this work, co-published by Inpatient Press and Espace Maurice in Montreal (where Goffman recently had an exhibition), is a fantasy novella she wrote. In addition to short fiction I wrote centering the Diller Scofidio + Renfro High Line, it also includes images of Goffman’s artwork and a letter by Alyssa Davis (who’s also shown the artist at her eponymous gallery). We recently celebrated the launch of the book amidst the burlesque glamour of the legendary Russian Samovar in the nearby theater district. Later that week, when we met up for this interview, we convened in a Koreatown bar’s second-floor lounge, at the top of a mysteriously clandestine stairwell. Goffman apologetically described the joint as “steampunk” when I arrived. The scene felt out of a film-noir movie set in a Sims render. Goffman was the only patron in a room of navy velvet high-backed chairs. Approaching from behind, I wasn’t sure it was her at first, her face obscured by the wide brim of an oversized rattan hat. This flare for drama is consistent through all of her work — especially her 3D-printed models of castles, train stations, and ornate façades adorned with balconies — earning her a starring role in the emergent discourse around “technoromanticism.” We talked, among other things, about nuclear architecture, kitschy motels, and Beaux-Arts booster Stanford White’s obsession with a stage actress for whom he built fantasy worlds.

Whitney Mallett: I see more and more art that’s explicitly about architecture. You make sculptures about the built environment, modeling buildings and typologies. I wonder how you see this impulse?

Genevieve Goffman: For some people, architecture has become kind of synonymous with nostalgia. I’ve talked about this with the artist Lola Dement Myers, who makes these amazing blueprint-like drawings of rooms based on her memories. People in our generation are harkening back to something they maybe didn’t even experience, and architecture becomes this way to look back. It’s often about history or a personal history ora conversation of identity through geographic location. Another example is my grad school classmate Anne Wu, whose work often references infrastructure in Flushing, New York where she grew up, and her experience moving from China to Queens. For me, it’s more of a temporal displacement: taking things out of time and place and putting them in another world.

A spread from Genevieve Goffman’s The Triumph of a Lonely Place. Photo courtesy of the artist.

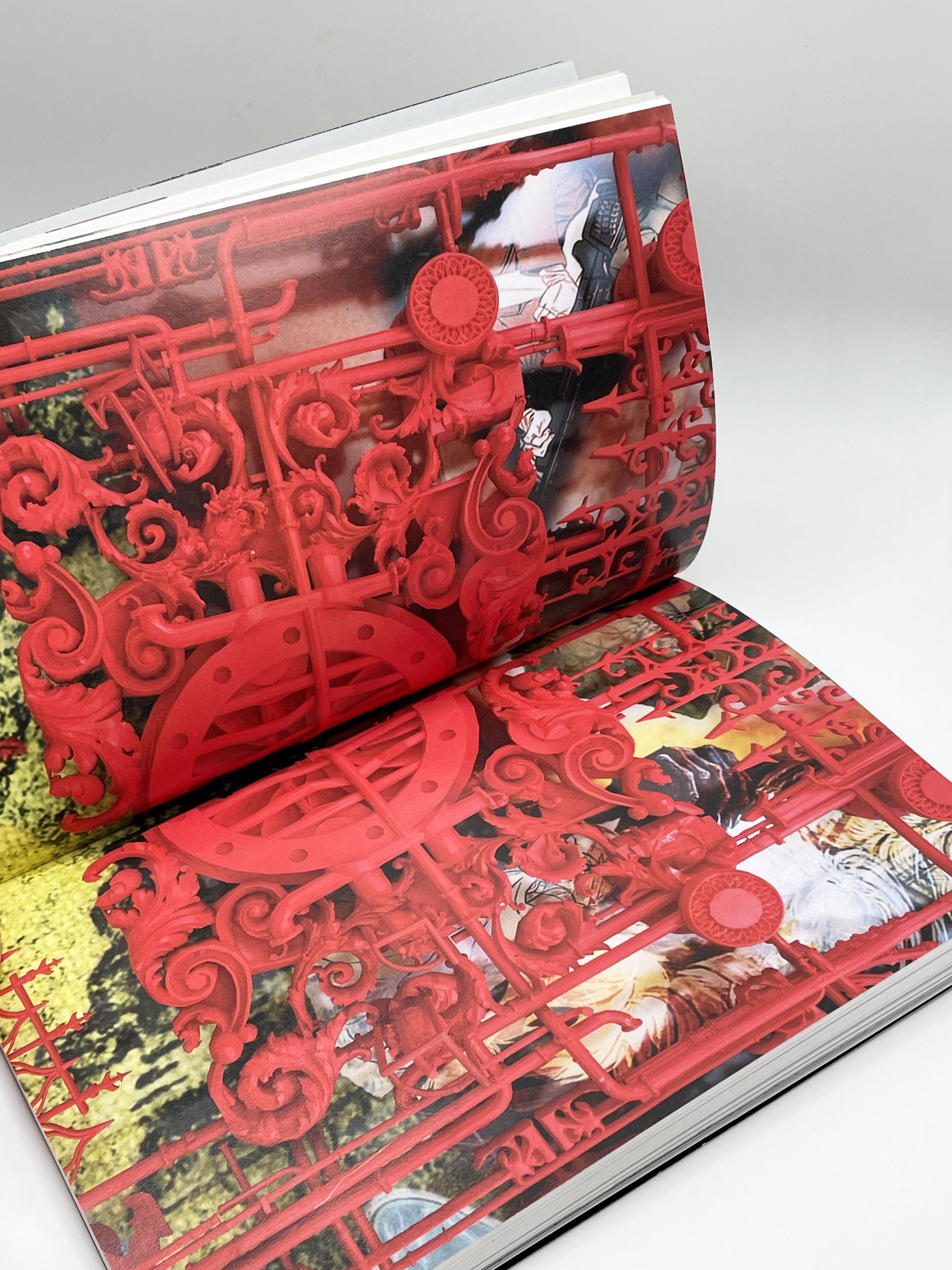

Genevieve Goffman’s The Triumph of a Lonely Place. Photo courtesy of the artist.

A spread from Genevieve Goffman’s The Triumph of a Lonely Place. Photo courtesy of the artist.

It’s interesting how architecture and urbanism lets artists engage with personal history in a way that lends legitimacy. Talking about a personal experience through a building typology is less likely to be dismissed as myopic. I think your work is similarly successful in juxtaposing architectural history and science fiction with girlishness and fantasy. The architectural research in your worldbuilding offers a defense against the dismissive responses employing the teenage girl archetype can trigger.

Early on, I was really struggling as an artist to find a voice I felt comfortable using. At first I felt that my work had to be very research-based. I was very concerned with being taken seriously. I wanted everyone to know how educated I was. And that I wasn’t just making art for no reason. I had science and facts to back me up. I had to learn to let that go and let things back in that I find beautiful and fascinating, which is often stories of girls in beautiful fantasy worlds. Fantasy animals and creatures really excite me. I’m interested in worldbuilding and bringing existing architecture into these fantasy worlds. I made a model of a fairy world version of the old Penn Station, creating my own version of that and building into it the idea of its destruction. How could I distort the identity of something that doesn’t exist anymore?

Portrait of Genevieve Goffman by Jeannie Sui Wonders for PIN–UP.

I like how you juxtapose architecture and fantasy because it underscores how our built environment is not inevitable — it’s the product of someone’s fantasy. I like the juxtaposition of our stories in this book because there are two types of post-industrial environments: a dystopian sci fi fantasy world with mutant hybrid creatures and the High Line. With every architectural intervention, someone had to project that vision.

Stanford White, who designed the original Penn Station, was absolutely delusional, or at least someone who was very actively living in his own fantasy world. He notoriously had this obsession with a young actress and model Evelyn Nesbit. He converted an entire room in his house just to fit his fantasy of her, recentering it around a velvet swing on which he had her sit and swing back and forth while he watched. I think it sometimes takes these people who have insane flights of fancy and egos to be architects. I can make jokes about the ego of architects and that pomposity but at the same time, this is someone building the world. It requires this grandiosity. Like the hubris it took to conceive and build something like the High Line. Now it’s there and we have to deal with it.

Right away we bonded over this idea of Disneyland-ification of industrial wreckage — the High Line becoming this tourist attraction is an interesting parallel to this world you dreamt up where there’s a fire in a tech server warehouse and the resultant melted debris becomes the site of this ecosystem of mutant fantastic creatures.

I like the absurdity of putting a Disneyland application onto disaster or ruin. I mean absurd in both something being ridiculous and also impossible. The High Line is ridiculous in some ways. Fantasy worlds like Disneyland are cheesy in this way that becomes comical. I like that slippage. I’m interested in this idea of collapse and points in time where systems of power have been crumbling. There’s a ridiculousness to the sort of architecture that’s created in these regimes, like the castles of Prussian royalty or what the Romans built.

Installation view of Genevieve Goffman’s The Triumph of A Lonely Place at Espace Maurice in Montréal. Photo courtesy of the artist.

We live in a time of hyper-decadence and you’re drawing from other moments of decadence in architecture and design.

We’re living in a time of hyper decadence, but worse, we also live in a time of hyper sterility.

Your story reminded me of Edgar Allan Poe’s Fall of the House of Usher. The house is expressing the decay of this aristocratic class. But Poe also has a whole book called Tales of the Grotesques and Arabesques. If we understand the uncanny as something at once familiar and strange, and the grotesque as something both attractive and repulsive, I think your story narrates this young girl’s encounter with the grotesque. Also the animals she’s drawn to are hybrids — like the snout of a pig on an owl. And then your gates, they embody a design definition of the grotesque, as in the grotto-esque: ornamentation that is not quite figurative but not wholly abstract either.

I actually have a very crazy Edgar Allan Poe story. When my uncle moved to Philadelphia from the Ukraine, he moved into this neighborhood, which at the time was a Jewish ghetto. At first he couldn’t figure out why these men would show up in white face paint and all black clothes and stand outside the house reciting terrifying poetry once a year. He was freaked out. Eventually he realized he was living in Edgar Allan Poe’s former house. Now it’s a museum. It’s a terrible museum mostly filled with cardboard cutouts, but there’s also a statue of a raven outside.

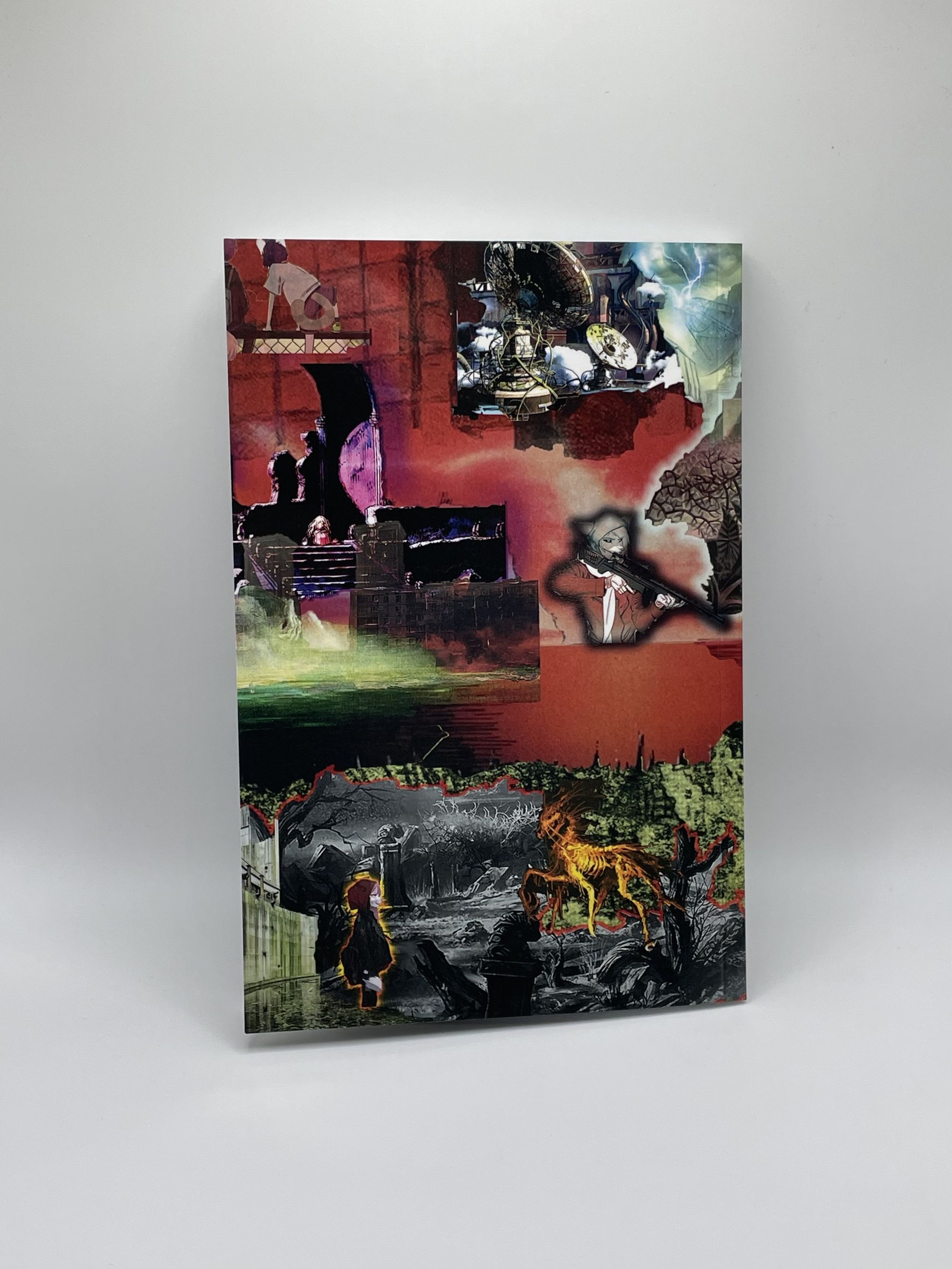

Dome # 1 (the sphere), Genevieve Goffman, 2024. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Dome # 1 (the sphere), Genevieve Goffman, 2024. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Let’s talk about some of the specific architectural motifs in your story. There’s this motel full of artificial taxidermy — conceived of by a man who loves animals and hates violence.

The motel was supposed to be this place of wonder and joy and now in the town there’s this absolute nightmare going on. It’s this beautiful place that was this man’s dream. His creation and imagination.

You introduce it as having this sky chalet typology. I learned a lot about the symbolic circulation of that typology working on the Barbie Dreamhouse book and researching the history of the A-frame in America. It’s functional for snow on roofs, but then it becomes associated with this kitschy reproduction of leisure. These fake trophy animals are also extremely kitschy.

One of the references is this very specific motel my boyfriend and I stayed in in Utah. It looked like if you took a Swiss ski chalet and remade it in the American Southwest. I wanted that sense of dislocation. It doesn’t matter where we are. It’s not specified what state this town is in. It’s funny my mom helped edit the book, and she kept trying to add in a happy ending for this motel owner, like he spent the rest of his days in Sante Fe. She was like, “This guy is so great, you have to give him a happy ending.” I was like, “No!”

His idiosyncrasies felt very much like a character from Twin Peaks.

It’s like the coastal horror: freaks living in these small towns. My grandmother was an opera singer who later moved to this small town in the Swiss alps where everyone had this weirdness, like the butcher would take off all his clothes and go outside and howl at the moon once a month. What happens in communities in a state of decline? What happens to people everyone knows are eccentric? What happens to the people who are Othered? What happens when a space stops to exist?

Portrait of Genevieve Goffman by Jeannie Sui Wonders for PIN–UP.

There’s this allegorical component to the book with the wall and the gate. The site of the tech server fire wreckage is cordoned off from the rest of the town. Inside this restricted zone things flourish. Outside things die, but there’s some porousness through the gate.

The inspiration behind the gate sculpture is nuclear architecture. There’s this idea that in the future we will need to design architecture to make people aware of where nuclear or toxic waste is. This architecture will need to be so alarming or off-putting that even people who can’t understand English will know not to go there. There are people who are like, “Oh, we’ll just have these spiky monoliths.” The pictures of this nuclear architecture that circulate online are really fantastic looking. How can you make something terrifying? It actually needs to be kind of amazing.

What do you make of this term technoromanticism? There was this essay in Spike Art Magazine recently by Kat Kitay called “What’s After Post-Internet Art?” that coined this term with you as an example.

I do think of myself as a romantic because I’m very interested in tragedy. My book is, like, quite tragic. And I use machining technologies to make my work. Some of the other artists I consider my peers, like Brian Oakes or Harris Rosenblum, make work that’s more of a commentary about technology itself. I’ve never really been an artist that makes work about the medium I work in. So other artists might be making romantic art about technology, whereas I’m using technology to make romantic art. Both with 3D printing and working in a sci-fi fantasy genre, there’s the potential to be doubly sidelined because some people don’t see either as serious or acceptable art. But I like being a contrarian. Still, I like being compared to other artists. It gives a sense of community and legitimacy in the narrative of art history.

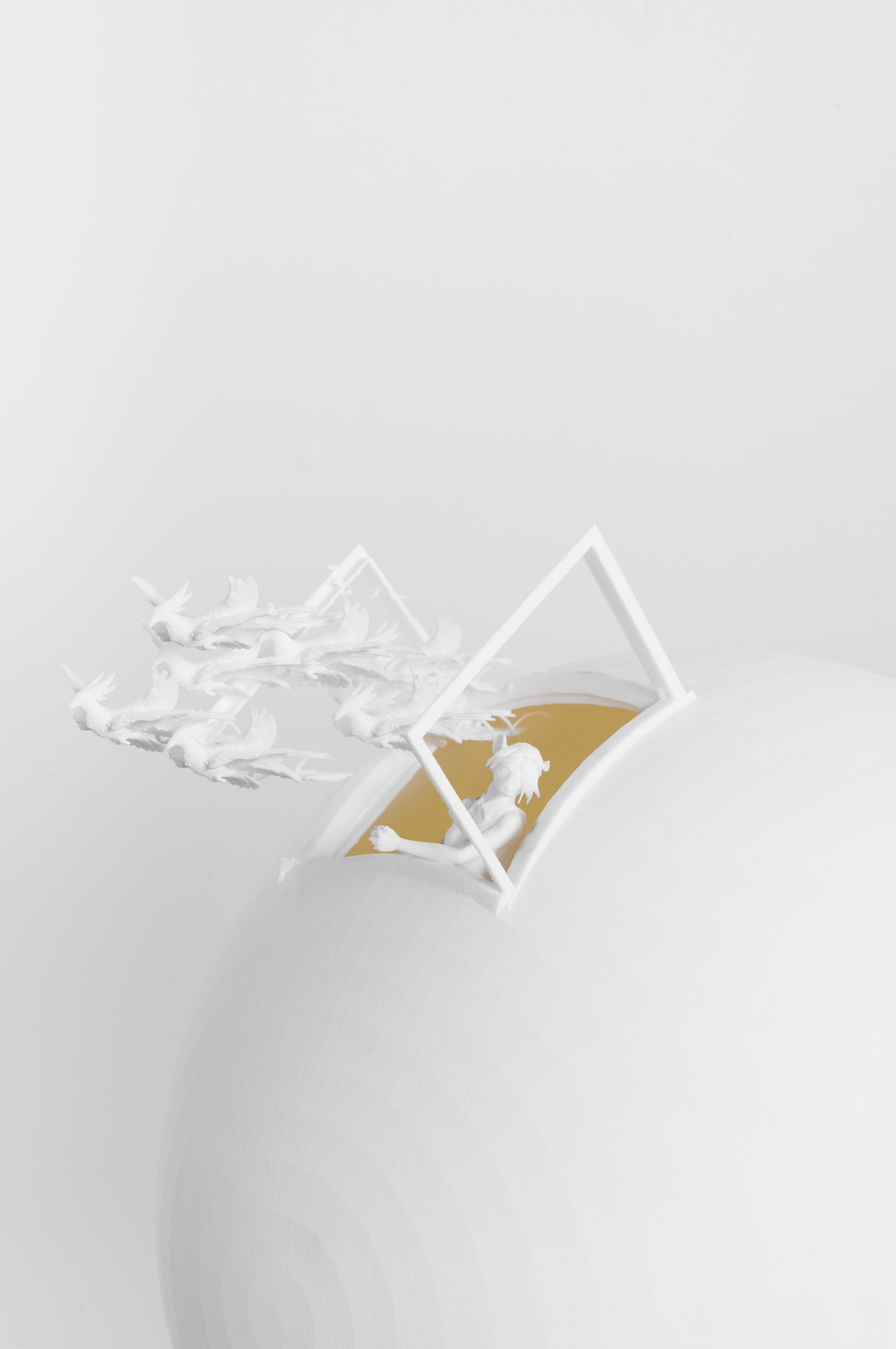

Detail view of A Women Will Never Sleep Again, Genevieve Goffman, 2024, Photo courtesy of the artist.

Detail view of A Women Will Never Sleep Again, Genevieve Goffman, 2024, Photo courtesy of the artist.

Detail view of A Women Will Never Sleep Again, Genevieve Goffman, 2024, Photo courtesy of the artist.

Have you ever read Jeff VanderMeer’s Annihilation, adapted into a major motion picture with Natalie Portman? Obviously your story creates a similar world and works in this genre Elvia Wilk has identified as “the new weird”: a mix between sci-fi and fantasy.

I haven’t read it. I know I should. My book is such, like, a cop on Annihilation. I never saw the movie either. But I read the Wikipedia article about it after I wrote mine.

There’s a key difference that I find interesting: in Annihilation, the protagonist is a scientist, but your protagonist is a young girl. I’m really interested in the archetype of the ingénue, or the Young-Girl (capital Y, capital G as defined by Tiqqun).

My girl is a creep. She’s a weird girl. She’s a curious and passionate person; kind of entitled with a bit of a victim complex. She has this Alice in Wonderland moment where she falls into this other space. I think part of being a teenager is being driven by your emotions instead of rationality.

Portrait of Genevieve Goffman by Jeannie Sui Wonders for PIN–UP.

And she’s driven by loneliness.

She’s very lonely. I think that desire to connect is the thing I like most about her or relate to most. I joke that she’s a femcel. I think about the ways loneliness and isolation can breed anger, resentment, dislike, and fear.

Through this post-apocalyptic town, you’ve created an exaggerated portrait of the angst many people who grow up in suburban or exurban areas feel. This is the root of her isolation. A lot of teenagers feel that way as a direct result of policy and development.

It’s like you’re experiencing something that you can’t quite grasp yet, and it’s being forced on you. You can’t take a step back. You’re just so fully immersed in this isolating infrastructure that’s consuming you.

Rem Koolhaas coined this term exurban, which refers to the developments on the periphery. And OMA actually made these renders of this whole development around data storage warehouses in America’s Great Basin desert, which included a hotel and art museum. I really like art that represents this cloud-storage infrastructure because it’s so often out of sight, out of mind. John Kelsey also made these watercolors depicting server warehouses.

I like the aesthetics of it. This endless world of wires and data, and how easily all of it can go wrong!