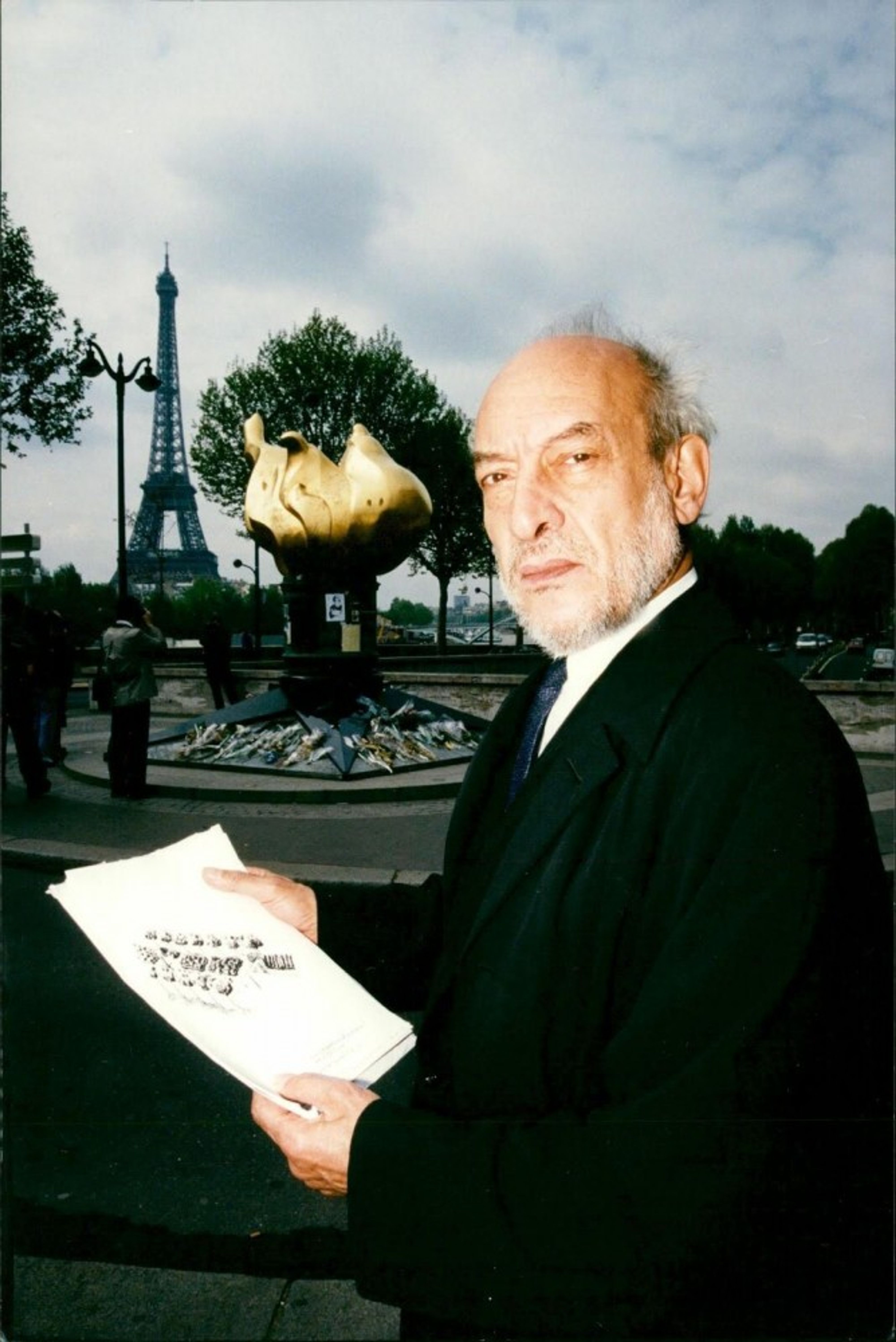

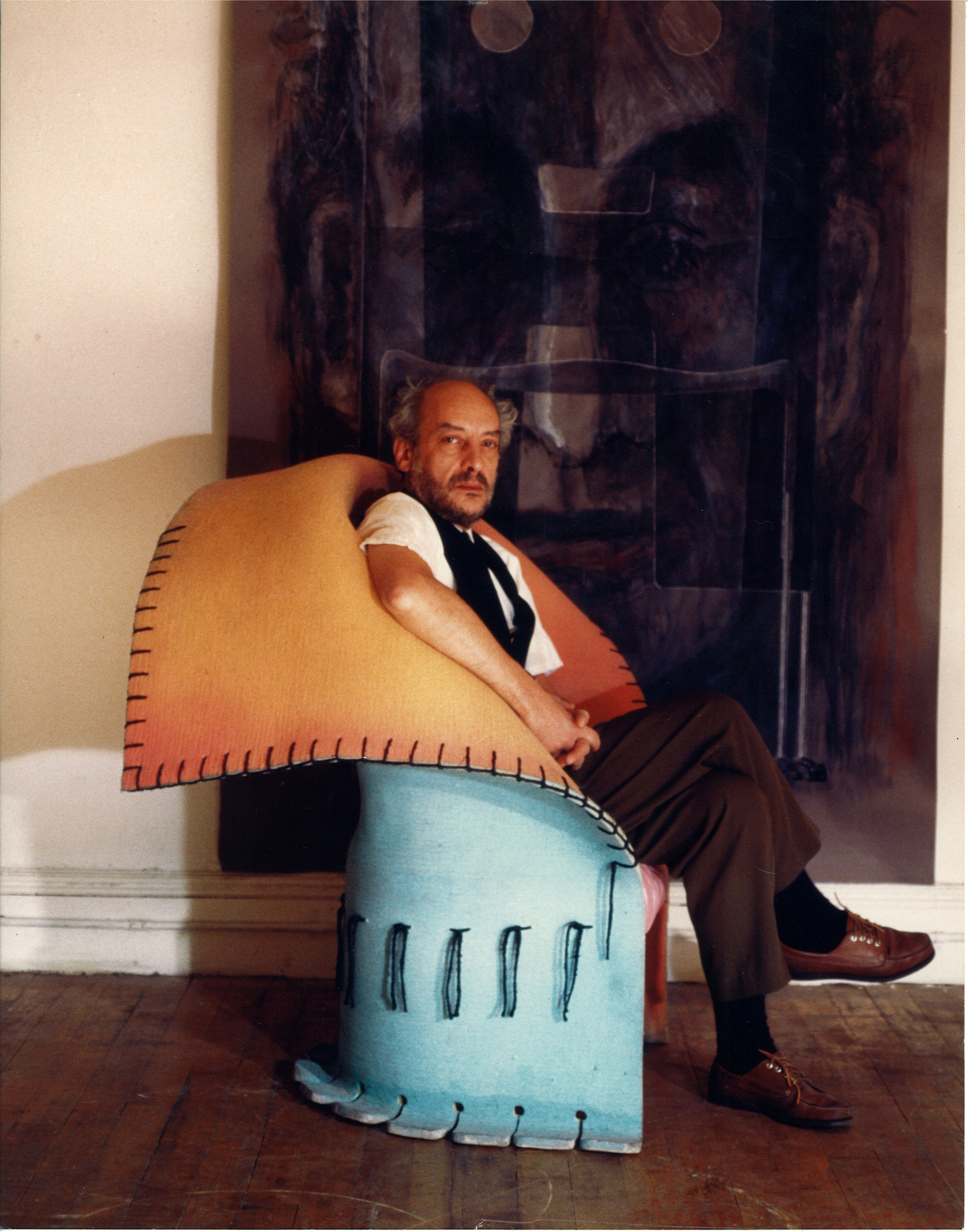

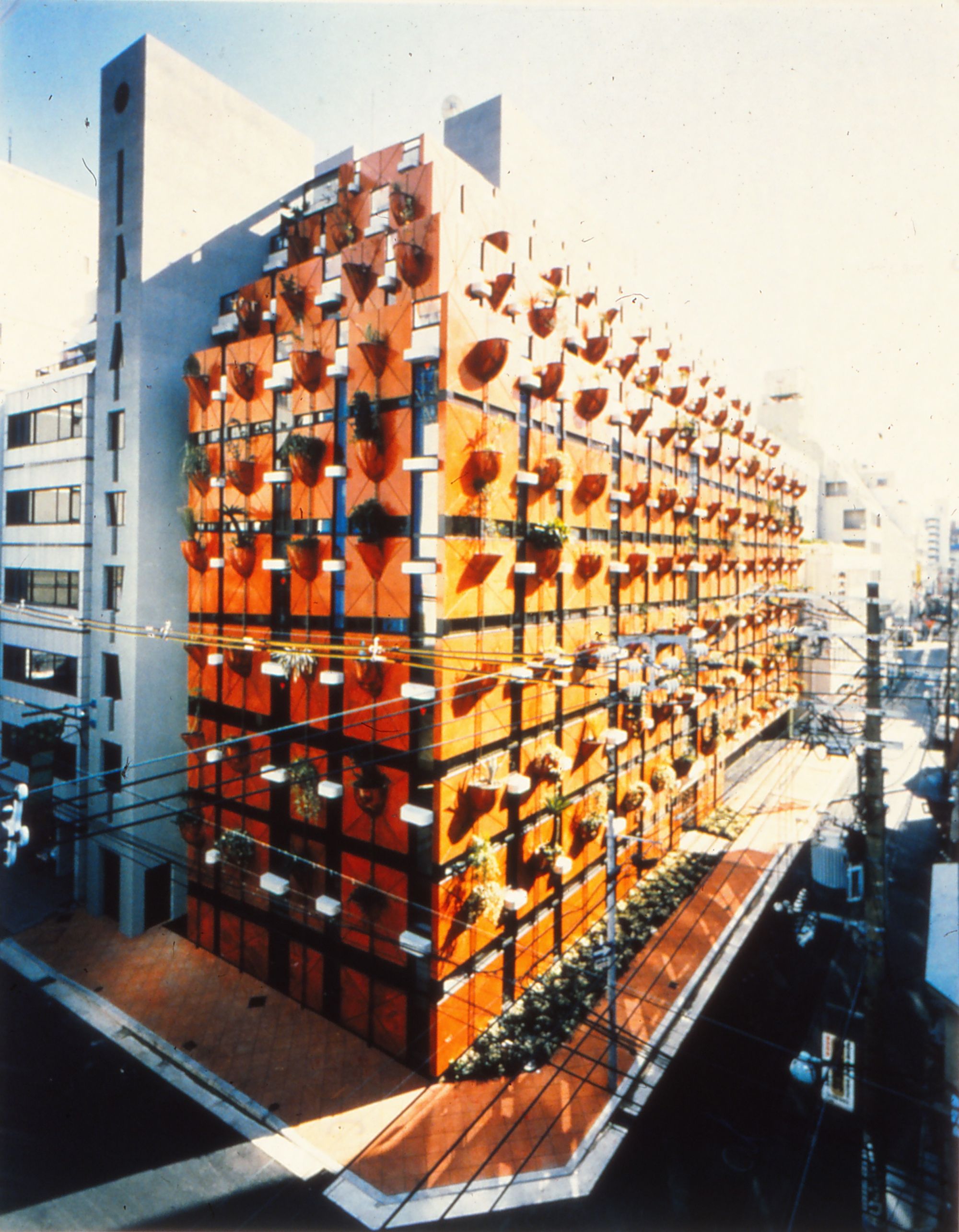

Gaetano Pesce needs little introduction. And yet, the 82-year-old is still full of surprises, especially for young designers. Born in northern Italy and raised by a single mother, the architect, designer, and artist studied architecture in Venice before being pulled into the vortex of 1960s experimentation in Radical Design. While many of his contemporaries either lost steam or settled on catering to the tastes of the bourgeoisie, Pesce never stopped experimenting with new materials, new shapes, new prophecies. The proudly incoherent oeuvre he’s created in the half century since spans media, furniture, art, and entire buildings — in Bahia, Osaka, Puglia — that have inspired generations of young creators since (myself included). Pesce thinks in color, shape, texture, materials, and the politics of storytelling, but everything he does is concerned with time: how does one embody it as an orchestrator of history? Our interview takes place in his large Brooklyn Navy Yard workshop in New York, the city he’s called home since 1980. It is from here that his designs, in signature materials like resin, fabric, and polyurethane, make their way into the world and into contemporary consciousness. Pesce never stops working, not even during the pandemic — his recent show at Salon 94, No More Silent Objects, is one of three he’s worked on this year. When I arrive at the studio, I immediately fall into a production line that requires me to insert myself into the scene, find my purpose among the workers, and settle into the task at hand: interviewing an icon.