Washi paper in Eriko Horiki's Kyoto showroom. Photo courtesy Eriko Horiki & Associates Co., Ltd.

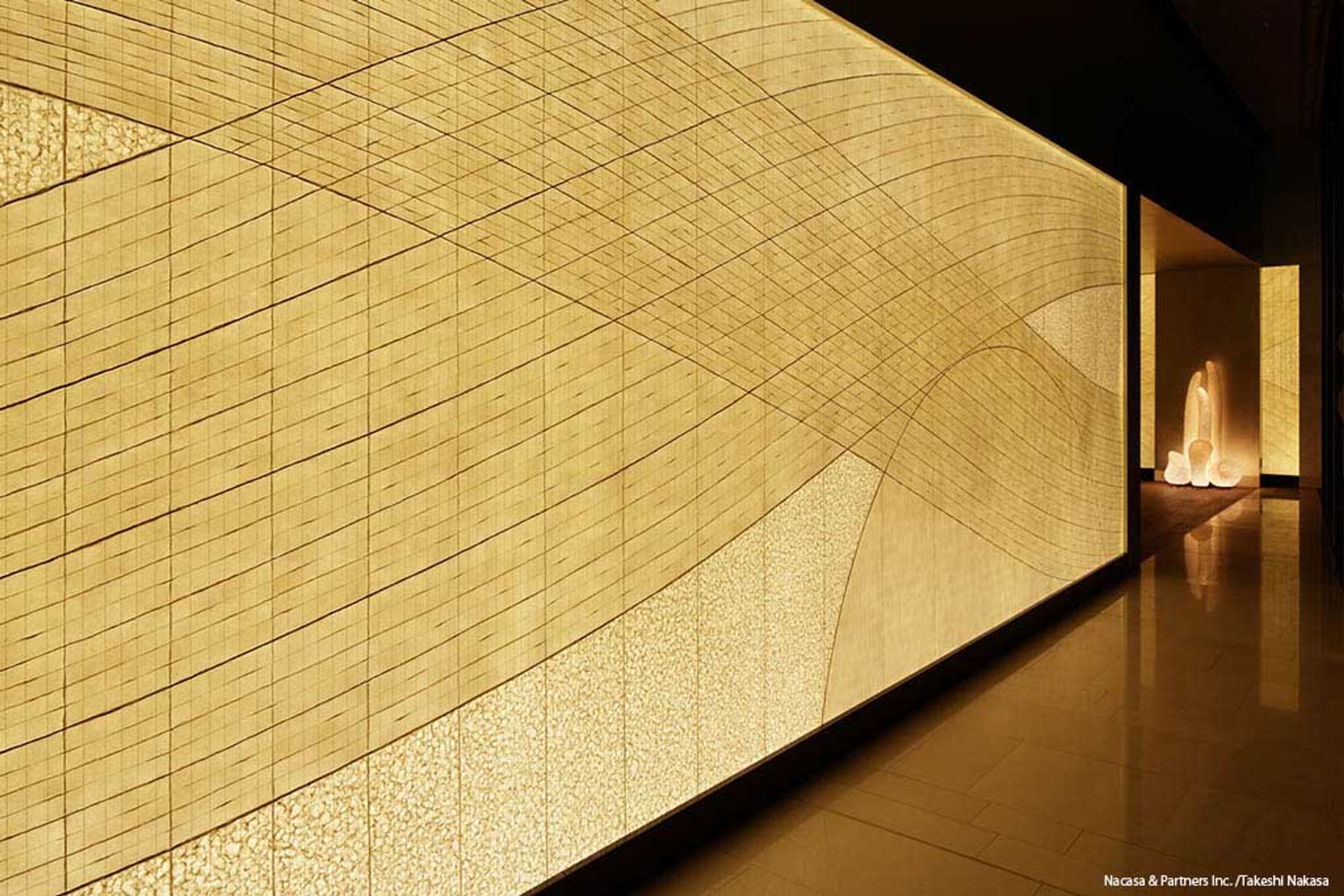

Eriko Horiki’s design for Yamabuki, the Olive Bay Hotel bar in Nagasaki (2013). Photography by Takeshi Nakasa.

It was the smaller-scale pieces in Eriko Horiki’s showroom in Kyoto that first caught my eye — a washi paper lamp or two in the corner, intricately designed yet the kind of object that’s not so hard to imagine in your own home. Across the room hung the opposite extreme: a washi chandelier adorned all over with massive Baccarat crystals — the Senritsu Lantern, made in collaboration with the crystal glass brand and its some 250 years of craftsmanship, which débuted at Salone del Mobile in 2011. But the showroom is built around a series of large-scale washi sheets, mounted on racks designed to slide into the middle of the space. These are captivatingly textured at first glance, some with intersecting stacks of lines, almost haylike, others punctuated with shimmering spots that almost look sponge-painted. But with a gradual switch of the track lighting above them, these washi sheets completely transform before your eyes. The grid of intersecting lines completely rearranges itself, and the shiny texture of the circular spots darken, flipping the pattern into something like a negative. Even when you’re bracing yourself for a shift, the effect is surprisingly dramatic.

The magic of Eriko Horiki’s washi paper lies in a dual embrace of what seem to be opposing forces: tradition and innovation. The Kyoto-born Horiki was working as a bank teller when she was asked to help with accounting and clerical work for a washi paper production company, which brought her into close contact with the centuries-old industry. According to the Nihon Shoki, the eighth-century chronicle of Japan, papermaking arrived in the early seventh century via Korean Buddhist monks, initially used for copying sutras as Buddhism spread across the archipelago. Over time, Japanese papermakers adapted the process, developing stronger papers using local plant fibers like kōzo, or paper mulberry. Until the Meiji period, when Japan rapidly modernized and Western materials entered daily use, washi was the dominant paper across the country.

Eriko Horiki making washi with craftsmen in Imadate. Photo courtesy Eriko Horiki & Associates Co., Ltd.

By the late 20th century, much of that handmade production had been displaced by machine-made paper, which was faster, cheaper, and easier to scale. Horiki, who had watched the papermakers of Imadate, Fukui work tirelessly in winter, their bare hands submerged in ice-cold water, was disheartened to see their culturally significant work sidelined by cost-driven production. The paper they made — as pure white as possible — carried spiritual meaning, tied to purification and the gods. She set out to preserve the craft through innovation, adding colors and unconventional fibers to the mix. At first, “the craftsmen absolutely hated me.” Many years later, she won them over.

In spite of these traditional beginnings, washi has long been a material associated with modern design. Isamu Noguchi’s Akari light sculptures, which he started making in the 1950s, introduced the material to an international audience. In the decades since, architects and designers, from Tadao Ando to Kengo Kuma, have repeatedly turned to washi for its translucency and capacity to modulate light. Most applications treat washi as a surface, used in walls, screens, or ceilings. But Horiki’s practice makes the paper itself a site of construction. Her washi is built in three to seven layers: pure white sheets on the top and bottom, with a designed layer (or multiple) between that incorporates dyed fibers, hand-spun silk, or silver foil. When light passes through her washi, it exposes this middle layer and reveals hidden patterns — the same mechanism at play in the showroom’s small dramas.

Washi paper in Eriko Horiki's Kyoto showroom. Photo courtesy Eriko Horiki & Associates Co., Ltd.

Washi paper in Eriko Horiki's Kyoto showroom. Photo courtesy Eriko Horiki & Associates Co., Ltd.

One of the first moments that brought her work to a broader public was her collaboration with House of Suntory, whose Hibiki whisky labels now use Horiki’s custom washi. The partnership, which began in 1989, marked a turning point in her career, bringing a global industrial system into the artisanal or sculptural register of handmade paper. House of Suntory has long paired its products with artists who reflect its philosophy, including a recent collaboration with waterfall painter Hiroshi Senju. His monumental waterfall work unfolds across the packaging for Hibiki 21 Years Old and Hibiki 30 Years Old. Built from ten shades of deep purple associated with Hibiki, the painting is made by flooding canvas panels with water and natural marble powder; gravity pulls the pigment downward into striated falls that then wrap the bottles and presentation cases. Senju described the collaboration as “a shared resonance between Hibiki’s core principle of harmony and artistry rooted in nature,” adding that it was “not just a commercial project, but a confluence of two forms of Japanese artistry.” Horiki’s work with House of Suntory is the same, translating the brand’s reverence for nature, water, and time into a surface that quite literally holds those values within its fibers.

Horiki’s washi paper scales from whisky bottle to large-scale public installations in hotels, airports, civic interiors, and retail spaces. Between 2007 and 2009, she created monumental washi installations across Japan, nearly 100-foot-long light walls with spiraling forms embedded into ceilings in Kanagawa, Osaka, and Yamaguchi. For a 2012 Tokyo installation, she designed a sequence of seven walk-through washi gates, each embedded with threads dyed in the seven colors of the rainbow. Her experiments have also extended beyond buildings altogether. In collaboration with calligrapher Yoko Yamamoto, Horiki developed a resin-based, three-dimensional washi technique for an electric concept car fitted inside and out with washi, which débuted at the Expo 2000 in Hannover, Germany. And at the International Festival UTAGE 2013 in Osaka, her washi towers were animated with projected imagery, bringing digital technology into direct conversation with tradition.

Below, Horiki reflects on how she arrived at washi from outside the craft world, the relationship between function and ornament, and why she believes the future of handmade materials depends on their ability to change.

Eriko Horiki's exterior for Minamoto Kitchoan Ginza Main Store in Tokyo (2019). Photography by Nacása & Partners Inc.

Eriko Horiki's exterior for Minamoto Kitchoan Ginza Main Store in Tokyo (2019). Photography by Nacása & Partners Inc.

Eriko Horiki's exterior for Minamoto Kitchoan Ginza Main Store in Tokyo (2019). Photography by Nacása & Partners Inc.

Eriko Horiki’s design for Yamabuki, the Olive Bay Hotel bar in Nagasaki (2013). Photography by Takeshi Nakasa.

Eriko Horiki's Prayers Through Washi in Tokyo (2012). Photography by Satoshi Asakawa.

Rachel Hahn: Before becoming a washi maker, you worked at a bank. What from that experience stayed with you once you moved into craft?

Eriko Horiki: I actually began my career as a teller at a large bank. One day, by coincidence, I was asked by someone to help with office administration and accounting for a small company owned by their son. That small business turned out to be a handmade washi paper production company. I wasn’t a born artist; I just helped with their bookkeeping and customer service. But that encounter pulled me into the world of crafts and craftsmanship, which was a world completely new to me. When I began working with craftsmen, they would often say, “No, that’s impossible.” Because I didn’t understand the usual limitations, I kept asking why and tried anyway — and sometimes, it worked. Not knowing the rules gave me freedom to challenge them. The first company I worked for was a small washi production company, but unfortunately, it closed just two years after I joined. They made exquisite handmade papers, but competitors began replicating their designs using machines. Machine-made versions were far cheaper, and in the paper market, handmade is often seen as expensive, while machine-made is considered affordable. It was believed that replacing handmade washi with machine-made alternatives strip away the spirit and living heritage that define this timeless craft. Naturally, most customers chose the cheaper option, and the company couldn’t compete. I found this deeply disheartening. I had seen how tirelessly the craftsmen worked — especially in winter, handling freezing water every day. Handmade washi embodies nature and the spirit of craftsmanship; it’s not just a product, but it carries culture and legacy. Despite their dedication to creating something beautiful, they couldn’t survive in the modern market. That is why I began to think we should propose ways to distinguish the roles of machine-made and handmade washi, and leverage the strengths of each.

Eriko Horiki and craftsmen making washi paper. Photo courtesy Eriko Horiki & Associates Co., Ltd.

When did you decide to study it seriously?

I was hoping someone would come along and change the washi world — to be a real game-changer — but no one did. So, at 25, I decided to start my own brand. In the first year, of course, I knew nothing about papermaking. I had no skills, no techniques, no knowledge at all. At that time, I did have support from a kimono wholesaler who understood the importance of developing Japanese culture, but even so, the first year ended with a significant loss. I asked 100 of my friends what I should do, and 120 told me to give up. The extra 20 were people I hadn’t even asked who approached me and said, “Stop doing this. You’re crazy.” They reminded me that I had never studied design at university, never trained under a craftsman, and knew nothing about the industry and business. I was in an extremely difficult position, and whenever I find myself in such a situation, I try to return to my starting point.

Tell me more about that first moment when you saw the papermakers at work in Imadate. How did you want to modernize their work?

About 38 years ago, I remember visiting the washi craftsmen in Imadate, Fukui, for the first time — the craftsmen absolutely hated me. They didn’t want to work with me at all. I greeted them, but they ignored me; they didn’t like me. Now you can probably understand why I often talk about white paper and its sacred connection to purification and the gods. For the craftsmen, that belief is deeply important. And there I was, a person with no background in papermaking, coming into their studio and proposing to add color and different materials. For them, this was almost unthinkable. They had preserved a 1,300-year tradition of making paper as pure and white as possible, with no foreign substances. And I was suggesting the complete opposite. At that time, I didn’t understand their philosophy. I didn’t realize how sacred white paper was to them. So, at first, I tried hard to convince them to modernize, but they completely rejected the idea. After learning more about their beliefs, I decided to stop “persuading” and instead focus on “continuing” to do what I believed was right in my own work. It took five years before they returned my greeting, and eight years before we could finally work together in collaboration.

Eriko Horiki’s design for Yamabuki, the Olive Bay Hotel bar in Nagasaki (2013). Photography by Takeshi Nakasa.

Can you tell me about your collaboration with House of Suntory? How do you make this high-quality washi at an industrial scale?

If you look at Suntory’s website, their corporate slogan says, “Sustained by Nature and Water.” That philosophy resonates deeply with the spirit of washi. Washi-making is deeply connected to water. When you try to create a good whisky, you can probably control much of the process — the ingredients, the aging, the craftsmanship. Yet the final outcome ultimately depends on nature: the temperature, the material, and the water quality. There’s always an element of randomness, of surrender in the pursuit of perfection. Trying to control everything is, I think, a kind of human arrogance. The Suntory label uses a smaller washi sheet: about 3 by 2 feet. Suntory approaches me with an idea inspired by the spirit itself: its taste, story, and image. Based on that concept, I design and create washi using 80 to 100 different techniques. Each sheet has a unique texture and pattern, and Suntory’s design team chooses just one. But the challenge doesn’t end there. If the designer says, “I like this part of the paper,” we then have to reproduce that exact texture consistently across every sheet — something that’s easy for an art piece, but extremely demanding when ensuring the same quality for consumers around the world. To achieve that, we collaborate closely with traditional artisans. When I ask them to try something completely new, they usually say no three times before agreeing — but that’s part of the process. It’s this dialogue between tradition and innovation that allows us to make high-quality washi for Suntory.

Historically, washi appears in shoji screens, but your work operates at a different scale — airports, hotels, large public interiors. Do you think about these spiritual or symbolic qualities of washi when working in public or communal spaces?

When I give lectures at universities, I often ask my students, “Do you know why we wrap gifts with white paper?” Most of them don’t know. Traditionally, white paper has a spiritual meaning — it purifies and protects. We purify our gift before giving it to someone. You can see this symbolism at Shinto shrines, where white paper hangs from ropes at the entrance gates, marking the boundary between the human world and the world of the gods. When I think about washi in public or communal spaces, I often go back to the origins of making things. If we look at ancient artifacts — pottery, tools, human figures — unearthed from the ground, most were made by ordinary people, not artists or designers. In Japan, there was a widespread custom of creating human figures or dolls as substitutes for oneself in times of hardship. For example, if someone was ill, they would make a doll and believe that by breaking it, their sickness or bad luck could be transferred to the doll and disappear. Behind these potteries and figures, there were always prayers, expressions of hope, protection, and reverence for life. But if we look at objects like pottery or plates, they’re not only symbolic; they’re also functional. People made them to hold water, rice, or food. They wanted both meaning and practicality. So yes, making things as a form of prayer and showing respect for life is very important — but unless I also give my work a practical, user-friendly function, people today won’t connect with it. It’s not enough to simply make washi beautiful; we must also tackle challenges such as making it fire-resistant, tear-resistant, stain-resistant, non-discoloring, and improving its precision.

Exhibition Tour ERIKO HORIKI – Prayers through Washi. Photo courtesy Eriko Horiki & Associates Co., Ltd.

What do you hope for the future of the craft?

I owe a great deal to Suntory. Through our collaboration, I’ve come to realize that when we talk about traditions, some people believe it must be preserved exactly as it is, without altering ancient methods or expressions. But I don’t believe that is enough. Traditions must evolve, be adapted to our modern lifestyles, and meet the needs of the times. Otherwise, mere preservation is not sustainable. What matters most is the spirit of the craftsmen behind each piece and the sense of aesthetics inherent to the Japanese people. Even if the methods or tools change, we must carry forward the stories behind the objects themselves. It is about passing on to the future the very essence of the Japanese spirit — a reverence for nature and a prayer for life — which is directly rooted in the land of the eight million gods.

Eriko Horiki's Prayers Through Washi in Tokyo (2012). Photography by Satoshi Asakawa.