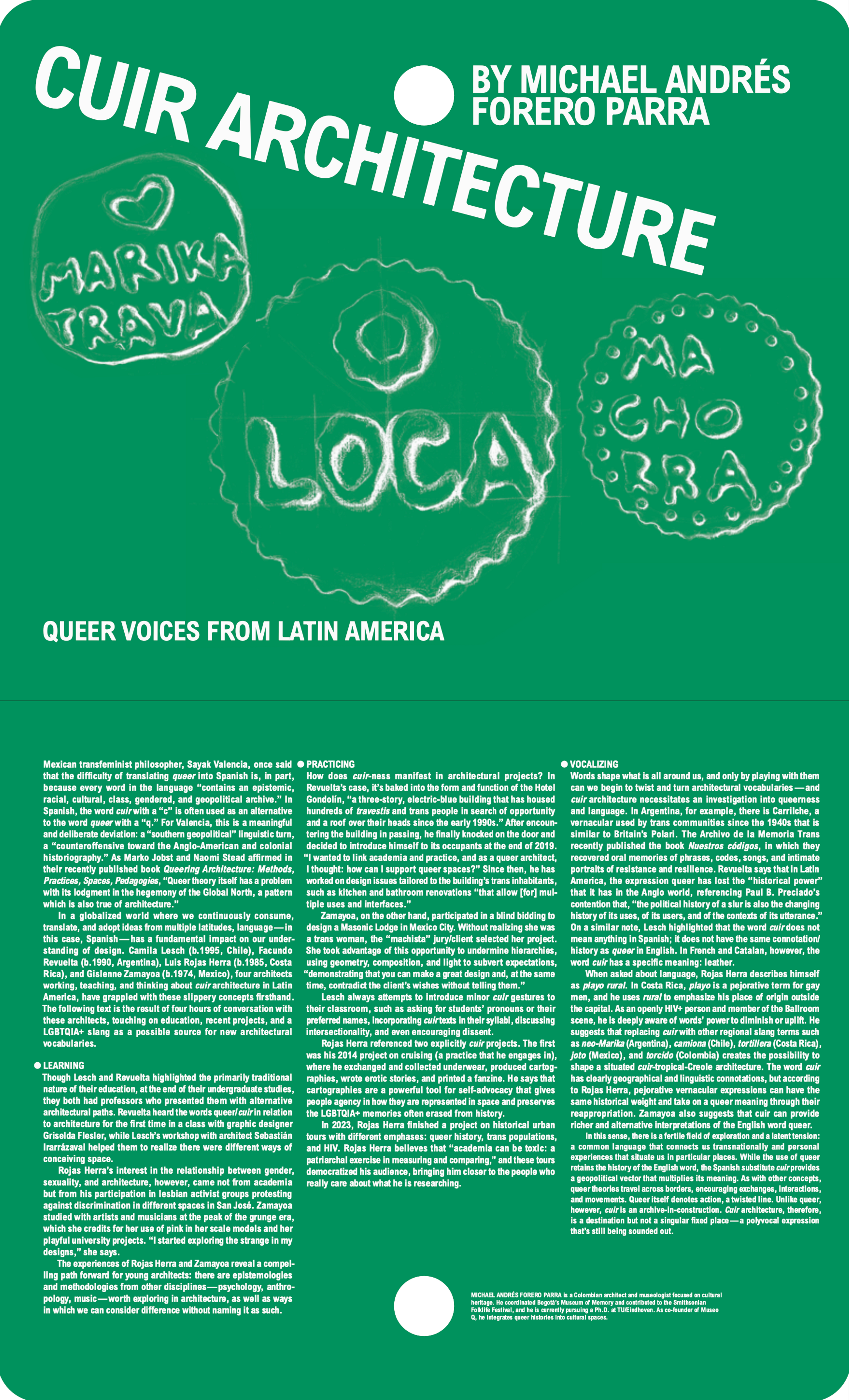

CUIR ARCHITECTURE

QUEER VOICES FROM LATIN AMERICA

by Michael Andrés Forero Parra

Illustration by Raphael Ganz for PIN–UP and Nieuwe Insituut Design Drafts #2.

Mexican transfeminist philosopher, Sayak Valencia, once said that the difficulty of translating queer into Spanish is, in part, because every word in the language “contains an epistemic, racial, cultural, class, gendered, and geopolitical archive.” In Spanish, the word cuir with a “c” is often used as an alternative to the word queer with a “q.” For Valencia, this is a meaningful and deliberate deviation: a “southern geopolitical” linguistic turn, a “counteroffensive toward the Anglo-American and colonial historiography.” As Marko Jobst and Naomi Stead affirmed in their recently published book Queering Architecture: Methods, Practices, Spaces, Pedagogies, “Queer theory itself has a problem with its lodgment in the hegemony of the Global North, a pattern which is also true of architecture.”

In a globalized world where we continuously consume, translate, and adopt ideas from multiple latitudes, language — in this case, Spanish — has a fundamental impact on our understanding of design. Camila Lesch (b.1995, Chile), Facundo Revuelta (b.1990, Argentina), Luis Rojas Herra (b.1985, Costa Rica), and Gislenne Zamayoa (b.1974, Mexico), four architects working, teaching, and thinking about cuir architecture in Latin America, have grappled with these slippery concepts firsthand. The following text is the result of four hours of conversation with these architects, touching on education, recent projects, and a LGBTQIA+ slang as a possible source for new architectural vocabularies.

Learning

Though Lesch and Revuelta highlighted the primarily traditional nature of their education, at the end of their undergraduate studies, they both had professors who presented them with alternative architectural paths. Revuelta heard the words queer/cuir in relation to architecture for the first time in a class with graphic designer Griselda Flesler, while Lesch’s workshop with architect Sebastián Irarrázaval helped them to realize there were different ways of conceiving space.

Rojas Herra’s interest in the relationship between gender, sexuality, and architecture, however, came not from academia but from his participation in lesbian activist groups protesting against discrimination in different spaces in San José. Zamayoa studied with artists and musicians at the peak of the grunge era, which she credits for her use of pink in her scale models and her playful university projects. “I started exploring the strange in my designs,” she says.

The experiences of Rojas Herra and Zamayoa reveal a compelling path forward for young architects: there are epistemologies and methodologies from other disciplines — psychology, anthropology, music — worth exploring in architecture, as well as ways in which we can consider difference without naming it as such.

Practicing

How does cuir-ness manifest in architectural projects? In Revuelta’s case, it’s baked into the form and function of the Hotel Gondolín, “a three-story, electric-blue building that has housed hundreds of travestis and trans people in search of opportunity and a roof over their heads since the early 1990s.” After encountering the building in passing, he finally knocked on the door and decided to introduce himself to its occupants at the end of 2019. “I wanted to link academia and practice, and as a queer architect, I thought: how can I support queer spaces?” Since then, he has worked on design issues tailored to the building’s trans inhabitants, such as kitchen and bathroom renovations “that allow [for] multiple uses and interfaces.”

Zamayoa, on the other hand, participated in a blind bidding to design a Masonic Lodge in Mexico City. Without realizing she was a trans woman, the “machista” jury/client selected her project. She took advantage of this opportunity to undermine hierarchies, using geometry, composition, and light to subvert expectations, “demonstrating that you can make a great design and, at the same time, contradict the client’s wishes without telling them.”

Lesch always attempts to introduce minor cuir gestures to their classroom, such as asking for students’ pronouns or their preferred names, incorporating cuir texts in their syllabi, discussing intersectionality, and even encouraging dissent.

Rojas Herra referenced two explicitly cuir projects. The first was his 2014 project on cruising (a practice that he engages in), where he exchanged and collected underwear, produced cartographies, wrote erotic stories, and printed a fanzine. He says that cartographies are a powerful tool for self-advocacy that gives people agency in how they are represented in space and preserves the LGBTQIA+ memories often erased from history.

In 2023, Rojas Herra finished a project on historical urban tours with different emphases: queer history, trans populations, and HIV. Rojas Herra believes that “academia can be toxic: a patriarchal exercise in measuring and comparing,” and these tours democratized his audience, bringing him closer to the people who really care about what he is researching.

Vocalizing

Words shape what is all around us, and only by playing with them can we begin to twist and turn architectural vocabularies — and cuir architecture necessitates an investigation into queerness and language. In Argentina, for example, there is Carrilche, a vernacular used by trans communities since the 1940s that is similar to Britain’s Polari. The Archivo de la Memoria Trans recently published the book Nuestros códigos, in which they recovered oral memories of phrases, codes, songs, and intimate portraits of resistance and resilience. Revuelta says that in Latin America, the expression queer has lost the “historical power” that it has in the Anglo world, referencing Paul Preciado’s contention that, “the political history of a slur is also the changing history of its uses, of its users, and of the contexts of its utterance.” On a similar note, Lesch highlighted that the word cuir does not mean anything in Spanish; it does not have the same connotation/history as queer in English. In French and Catalan, however, the word cuir has a specific meaning: leather.

When asked about language, Rojas Herra describes himself as playo rural. In Costa Rica, playo is a pejorative term for gay men, and he uses rural to emphasize his place of origin outside the capital. As an openly HIV+ person and member of the Ballroom scene, he is deeply aware of words’ power to diminish or uplift. He suggests that replacing cuir with other regional slang terms such as neo-Marika (Argentina), camiona (Chile), tortillera (Costa Rica), joto (Mexico), and torcido (Colombia), creates the possibility to shape a situated cuir-tropical-Creole architecture. The word cuir has clearly geographical and linguistic connotations, but according to Rojas Herra, pejorative vernacular expressions can have the same historical weight and take on a queer meaning through their reappropriation. Zamayoa also suggests that cuir can provide richer and alternative interpretations of the English word queer.

In this sense, there is a fertile field of exploration and a latent tension: a common language that connects us transnationally and personal experiences that situate us in particular places. While the use of queer retains the history of the English word, the Spanish substitute cuir provides a geopolitical vector that multiplies its meaning. As with other concepts, queer theories travel across borders, encouraging exchanges, interactions, and movements. Queer itself denotes action, a twisted line. Unlike queer, however, cuir is an archive-in-construction. Cuir architecture, therefore, is a destination but not a singular fixed place — a polyvocal expression that’s still being sounded out.

Design Drafts in PIN–UP 35.