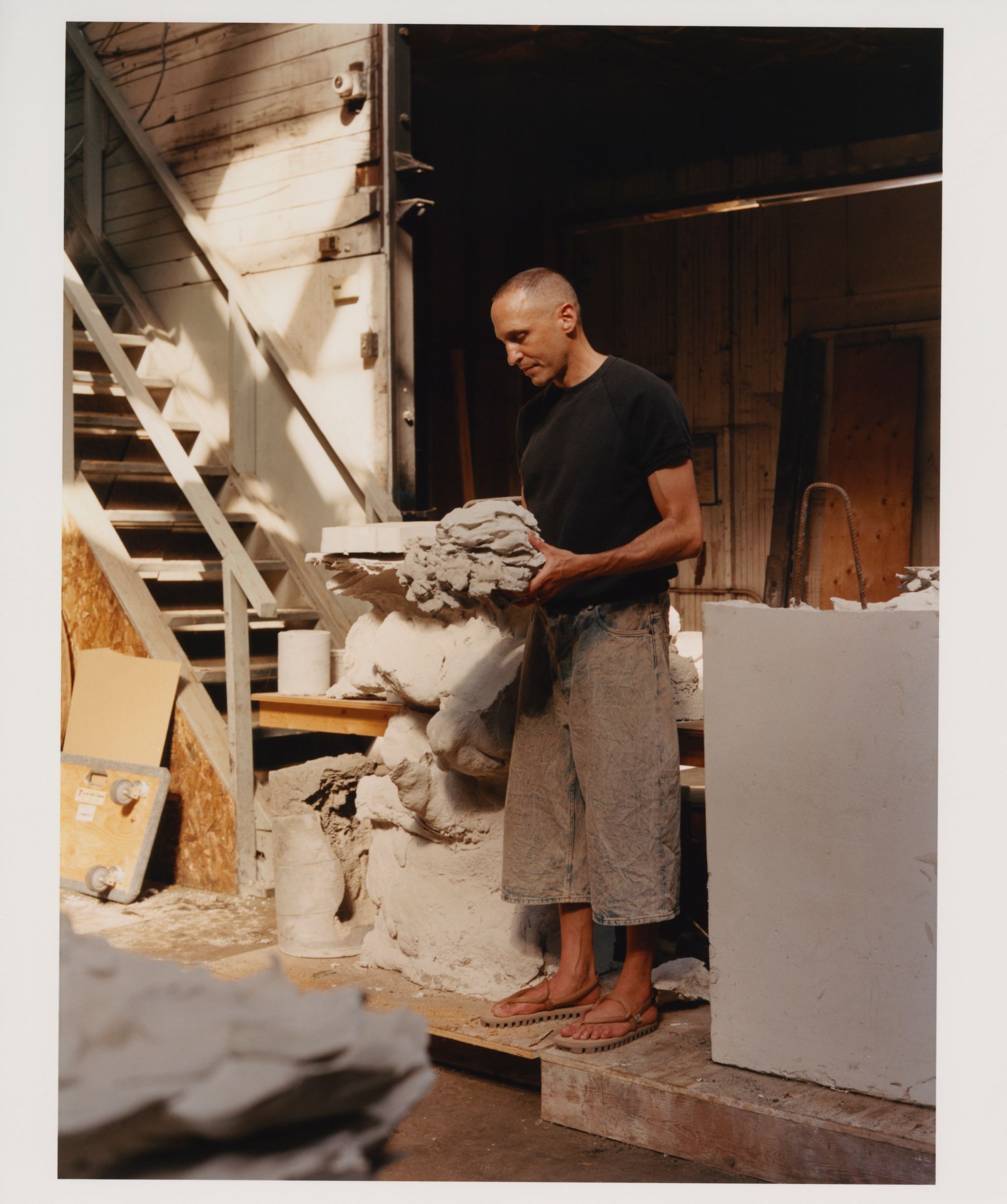

The most recent turn in their years-long journey together is the expansion of Omer Arbel Office (OAO), which finds the Bocci team designing a series of ground-up buildings in the Pacific Northwest. It’s a return, in effect, to Arbel’s professional roots, having spent years in a large corporate office before striking out on his own. “I always thought, if I could be an architect again, I would want to do it, but without the pressures.” The success of his and Bishop’s enterprise has enabled Arbel to do just that — and in grand fashion. As the Bocci team continues to fire up wild confections in their custom production facility, they’re working on buildings that are equally as inventive as any of the chandeliers and electrical systems that came before.

The office’s realized work currently comprises three houses, two in the Vancouver suburbs and a third on scenic Galliano, a forested island west of the city in the Strait of Georgia. The first predates the practice’s recent architectural turn: completed in 2010 for Bishop and his family, the 23.2 house served as a proof of concept, its bouquet of aslant concrete slabs offering a glimpse of what Arbel’s process-focused technique might yield at a larger scale. Just a short walk away is 75.9, an investigation into the possibilities of fabric-formed concrete that OAO completed last year. Its huge, tree-like piers — the rough, burlap grain of their fibrous molds still visible on their surfaces — serve as planters for actual trees above, the whole house subsumed into the rural landscape that surrounds it. The Galliano project is a more sedate meditation on the natural world, conceived as a sequence of bridges over a shallow ravine. On a site visit this summer, Arbel leaped excitedly around the wooden structure, pointing out its concealed sleeping quarters and peekaboo cut-throughs.