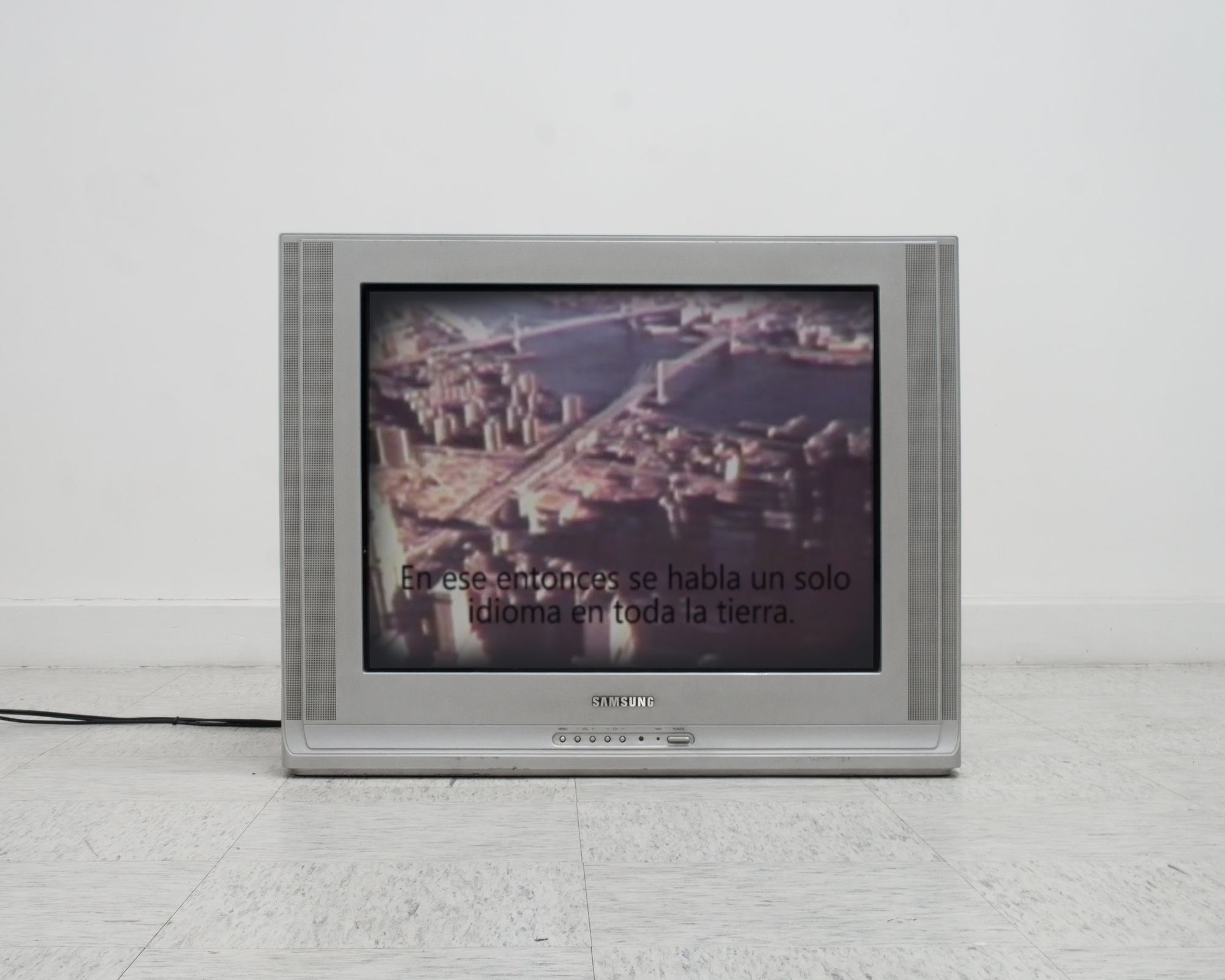

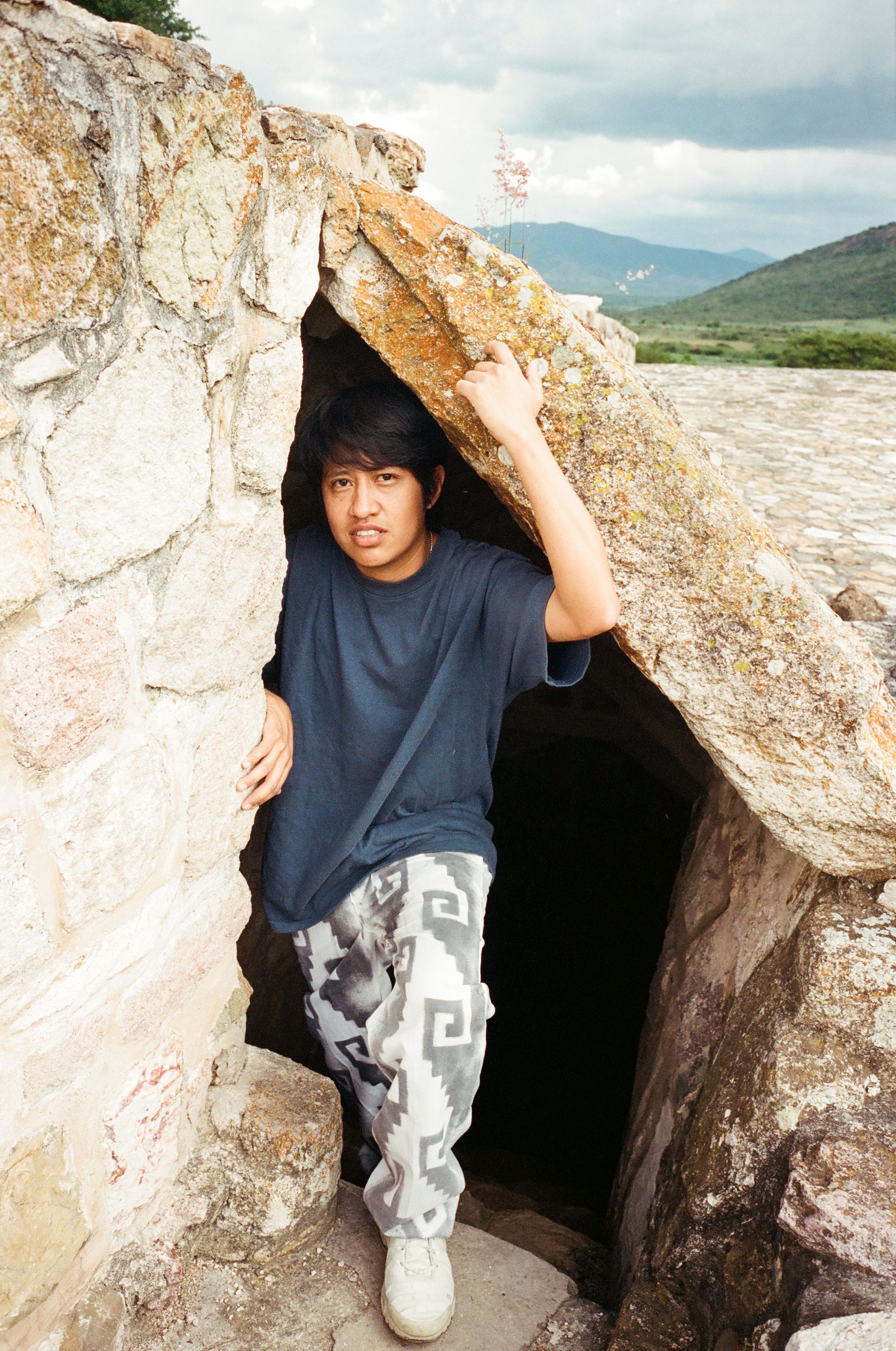

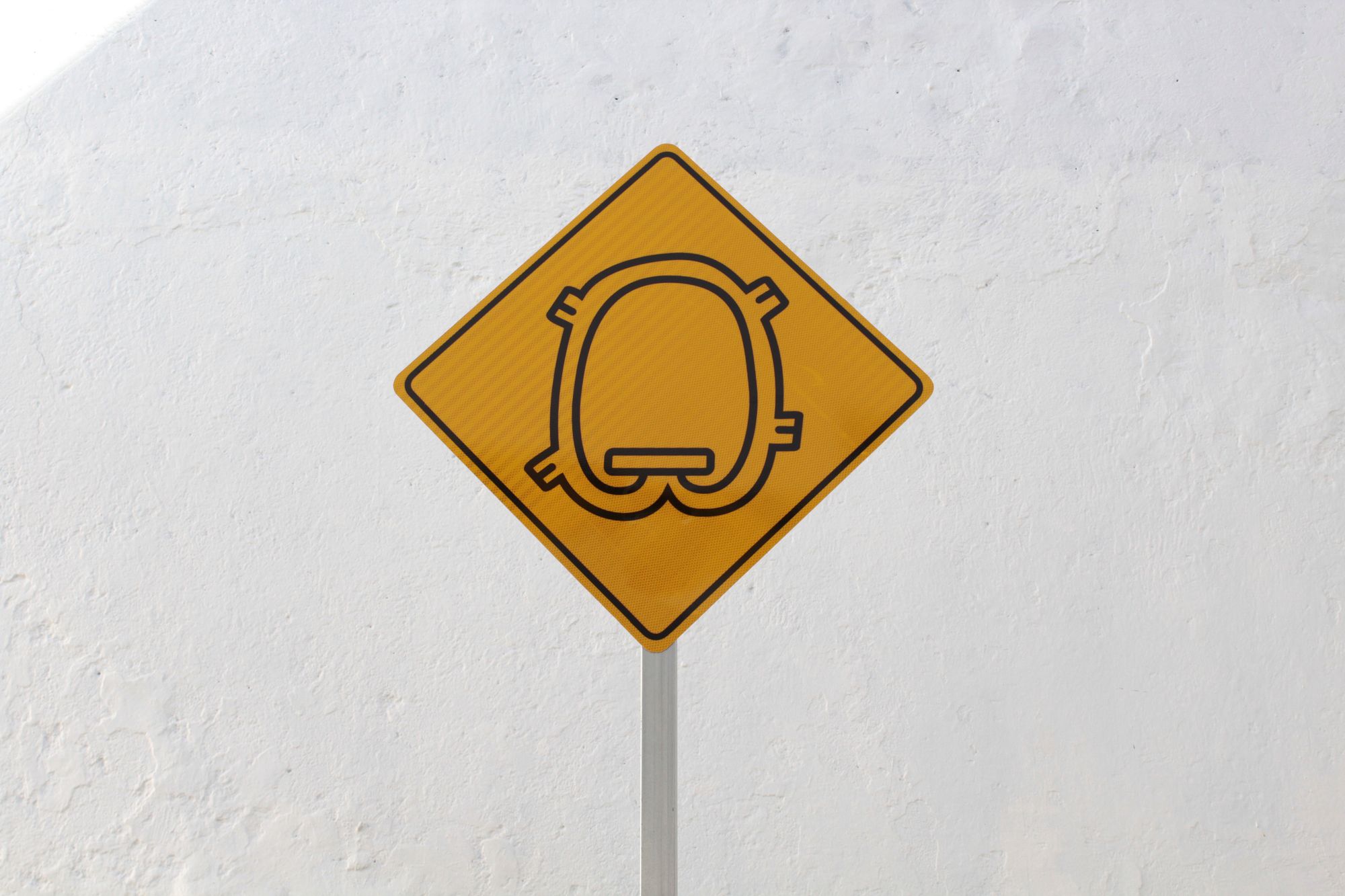

Andy Medina enters the video chat. His head is haloed by T-shirts hanging in the background, with designs realized with airbrush, the result of a collaborative project hosted by Yope Projects, the art collective Medina cofounded in 2017. The shirts depict busty anime girls, clown faces; Christian animation company Precious Moments’ Sad Sam holding a can of spray paint; and Mickey Mouse holding one as well. I’m in the capital, Mexico City, while Medina is in Oaxaca City, some 230 miles away, inside Yope Projects’ studio space, which is part community art hub that hosts exhibitions and workshops, part storefront for selling artists’ objects and merch, and also Medina’s personal studio. He pans his phone over to his workspace, revealing a mix of local vernacular iconography and nostalgic imagery. These everyday objects — found in gift shops or markets, online, and in the streets of his hometown — inform Medina’s mixed-media work, in which they are often recontextualized and transformed to interrogate labor, value, and community.I’m reminded of an opening I attended the night before, organized by the project space Aro. It was located in Pasaje Catedral, a mall in Mexico City’s historic center that specializes in Catholic paraphernalia. In between darkened window displays of rosaries and plaster saints flickered Genesis 11, a video piece by Medina from 2018. Using archival footage of the construction of the World Trade Center’s Twin Towers in the 1960s, a narrator recounts the story of the Tower of Babel in Mixtec, one of the many Indigenous languages spoken in the state of Oaxaca (with subtitles in Spanish). Made six years ago, the work engages many concepts that have subsequently preoccupied Medina in his practice: the limits of language, the possibilities of translation, and the interplay between symbols, identity, and architectural monuments.